In his Treatise on water, Leonardo says much more: “Water is sometimes sharp and sometimes strong, sometimes acid and sometimes bitter, sometimes thick or thin, sometimes it is seen bringing hurt or pestilence, at some time health-giving, sometimes poisonous. It suffers change into as many natures as are the different places through which it passes. And as the mirror changes with the color of its subject, so it alters with the nature of the place […] Sometimes it is the cause at times of life or death, or increase or privation, nourishes at times and at others does the contrary; and sometimes it floods. […] In time and with water, everything changes.”

There is little to add. The water flowing through the Earth in the 21st century confirms what the Tuscan genius observed in the 15th century; the difference is that now there are many billions more who need water, and it is much more poisoned than in Renaissance times. Leonardo did not live in the industrial age, nor did he see impoverished slums growing up, or rivers blocked by plastic and rubbish or turned into dumping grounds for all kinds of chemicals; if he had seen all this, he would have strengthened his metaphor, linking the health of rivers to the health of people. And today’s science would have confirmed it. If the water in the rivers gets sick, we all get sick.

Nothing is more linked to life than river water: life for us and life for nature. Rivers that have lost the life within them are the worst symptom of the Earth’s health.Turag river. © Shamima Prodhan/REACH

The We Art Water Film Festival’s testimony

River pollution affects us all, but those who live along the river suffer the most from its direct impact on their lives. Throughout the five editions of the We Art Water Film Festival, authors from all over the world have given testimony and helped us to see what many of us do not see. The contents of the short films have allowed us to communicate, provide visibility and reflect on what happens to water in any part of the world and what we could do to solve many of the severe problems we have.

River pollution affects us all, but those who live along the river suffer the most from its direct impact on their lives. Río Turag river. © Emily Barbour/REACH

In the case of rivers, the testimonies are shocking. And they lead us to recall Leonardo’s metaphor: “…[Water] suffers change into as many natures as are the different places through which it passes.” We invite you to take a look at some of the most significant ones:

The Buriganga

On the banks of the Buriganga in Dhaka (Bangladesh), there is barely any life left. More than 60,000 cubic meters of toxic waste are dumped daily into its waters. The main sources of pollution have been the leather tanning industry, mainly concentrated in the Hazaribagh neighborhood, and sewage discharges from the population living without proper sanitation.

Deadline, the short film by Raihan Ahmmed, accurately depicts the causes of the disaster and its consequences for the more than four million people who live by the river:

Deadline, by Raihan Ahmmed (Bangladesh), finalist in the micro-documentary category at the second edition of the We Art Water Film Festival.

Learn more about the Buriganga River

The Turag

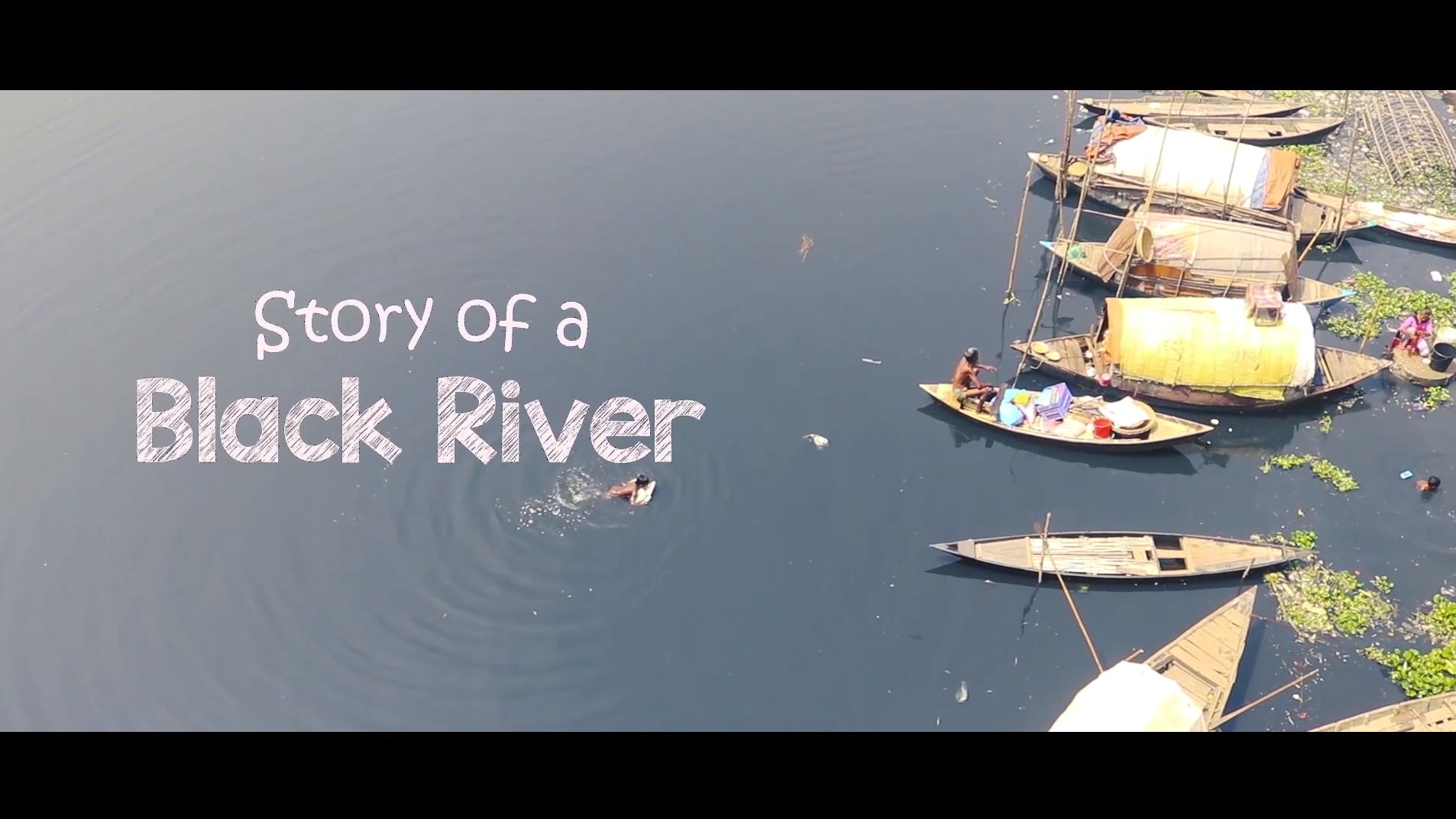

The Turag River is one of the most important tributaries of the Buriganga Riverand is responsible for much of its pollution. Many industries that have been set up in and around the city of Dhaka dump their waste into the river.

Story of a Black River, the short film by Sabbir, testifies to how water, poisoned by all kinds of discharges, destroys the health of those who depend directly on it:

Story of a Black Riverby Sabbir (Bangladesh), finalist in the micro-documentary category at the fifth edition of the We Art Water Film Festival.

The Mithi

Poverty is both cause and effect of water pollution. Sewage from slums such as Dharavi in Mumbai, which at over 216 hectares was ranked in 2012 as the largest slum in Asia, and illegal dumping have caused the 18 km of the Mithi riverbed to become an open sewer. In addition to unauthorized hazardous waste dumping in the 1970s, plastic pollution clogged many drains and made monsoon floods dangerous to the population.

The micro-documentary Plastic River, the short film by Maaz Kazmi, shows images that have become a sad icon of what is unacceptable:

Plastic River by Maaz Kazmi, (India), finalist in the micro-documentary category at the fifth edition of the We Art Water Film Festival.

The Musi

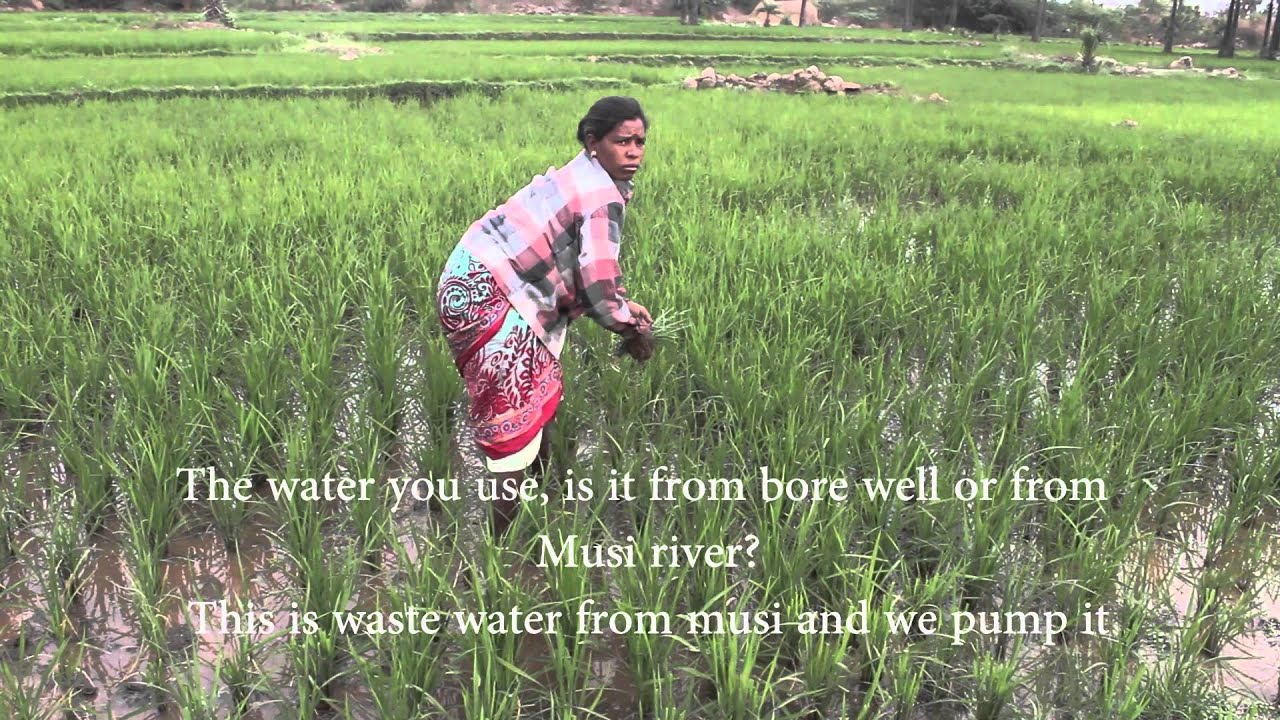

The Musi river basin receives 645 million liters of sewage a day that has surrounded the poorest inhabitants of its banks around the city of Hyderabad in India. Pollution has made diseases such as arthritis, diarrhea, jaundice, trachoma, and all kinds of skin allergies endemic in the area.

In the micro-documentary Necessity Triumphs, by Samir Bhattacharya, we can see how inevitably farmers and herders in the area are exposed to polluted water, as they use water from a precarious reverse osmosis plant for drinking, washing their cooking utensils, and doing their laundry:

Necessity Triumphsby Samir Bhattacharya (India), finalist in the micro-documentary category at the third edition of the We Art Water Film Festival.

Learn more about the Musi River

The Tanjaro

The ecosystem of the Tanjaro River in Iraqi Kurdistan has suffered from the destruction of its water treatment facilities, which were looted and sold after the Gulf War. The discharges went directly into the river, which became an open sewer. It was a ruin for agriculture and tourism, and most of the farmers had to migrate.

The short film Tanjaro is Dying, by Horen Gharib, traces the causes and disastrous effects of the river’s pollution in a part of the world that has little recollection of peace:

Tanjaro is Dying, by Horen Gharib, finalist in the micro-documentary category at the fifth edition of the We Art Water Film Festival.

Learn more about Tanjaro River

In time and with water, everything changes

UNESCO estimates that over 80% of wastewater is discharged into the environment untreated. Most of it ends up in rivers and goes into the sea or aquifers. Virtually all freshwater pollution and about 85% of global marine pollution result from human activities on the Earth’s surface. In many cases, the water damage is irreversible.

Virtually all freshwater pollution and about 85% of global marine pollution result from human activities on the Earth’s surface. Musi river.© pangalactic gargleblaster and the heart of gold

In recent years, rivers in industrialized regions have improved significantly thanks to stringent environmental regulations of governments and increased social responsibility of industries. However, most rivers in emerging economies are progressing very slowly, and the situation is worsening in many cases. Further assistance is needed in the search for funding for sanitation facilities. Public awareness of the water cycle as a universal natural capital, which knows no borders and is vital for the future of humanity, is the best incentive.