With the aim of improving communication in international collaboration, after the access to water vocabulary, we will analyze the terms used by the UN to define sanitation. Admittedly, they are more complex as the sanitation concept has very different meanings depending on geography, culture and, above all, economic wealth. However, halfway to culminating the 2030 Agenda, analyzing the meaning of this vocabulary clarifies the magnitude of the problem and shows the way to solutions.

The terms describing sanitation facilities in relation to the objectives set out by the SDG 6 refer to the health guarantees they can provide for humans. © E. von Muench

The SDG 6 and the sanitation targets

In the eight targets of SDG 6, target 6.2 specifically mentions sanitation and hygiene: “By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.”

In the eight targets of SDG 6, target 6.2 specifically mentions sanitation and hygiene: “By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all. © Hélène Figea

Target 6.3 addresses water quality and wastewater management: “By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.”

Data to track

Following the establishment of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, the UN appointed the WHO and UNICEF to oversee and monitor these three first targets through the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene.

In 2018, the JMP published global data on access to water and sanitation, adding hygiene data in 2019, just before the Covid-19 pandemic. Since then, this database has been the essential reference on the evolution of the key targets of SDG 6, establishing the essential unification of the technical jargon used. Most people had found it confusing and were not aware of the severe shortcomings of the human right to water and sanitation.

Let us take a look at the basic terms and the new indicators for their monitoring established by the JMP:

The vocabulary of target 6.2

Achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.

“Paying special attention to the needs of women and girls” means reducing the burden of fetching water and allowing women and girls to manage sanitation and hygiene needs with dignity. © Carlos Garriga / We Are Water Foundation

“Access” refers to having facilities close to home that are easy to access and easy to use when needed.

“Equitable” means there are no inequalities in access between different population groups (social classes, ethnicities, gender, etc.).

“Sanitation services” are the facilities and services that enable the safe management and disposal of urine and human feces.

“Hygiene” refers to the conditions and practices that help maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases; it includes handwashing, menstrual hygiene, and proper food handling.

“Adequate” refers to a system that hygienically separates excreta from human contact and allows the safe reuse and treatment of excreta in situ, or its transport or treatment offsite with acceptable health standards.

“For all” means that the services must be adequate for use by men, women, and children of all ages, including people with disabilities of any kind.

“End open defecation” means ending the practice of leaving excreted matter in a bush, a field, a beach, a street, or in any other outdoor space; or dumping it in a drainage channel, river or in the sea or any other body of water; or temporarily wrapping it in some material and then disposing of it.

“Paying special attention to the needs of women and girls” means reducing the burden of fetching water and allowing women and girls to manage sanitation and hygiene needs with dignity. Special attention must be paid to the needs of women and girls in “intensive use” environments, such as schools and workplaces, and in “high risk” environments, such as health and detention centers.

“And to people in vulnerable situations” refers to attending to the specific needs of “special cases”, such as refugee camps, detention centers, mass gatherings, and pilgrimages.

The vocabulary of target 6.3

Improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.

“Water quality” refers to its adequacy to safeguard human and environmental health.

“Wastewater”is the effluent of human use. It is polluted water from discharges of different origins: domestic, agricultural, industrial, and runoff.

“Untreated wastewater” refers to water that has not been subject to a series of physical, chemical, and biological processes to remove pollutants.

As we can see, this third target is directly related to human and environmental health. It is a significant threat to the planet that 80% of wastewater is not treated before it is discharged. According to UN Water, untreated water reaches 30% in rich countries, which rises to 62% in upper-middle-income countries and soars to 72% in lower-middle-income countries. In developing countries, 92% of wastewater is untreated.

The key indicator: Who has safely managed sanitation?

Similarly to target 6.1 concerning access to water, the JMP created in 2017 a new key indicator for monitoring target 6.2: “proportion of population using safely managed sanitation services, including a handwashing facility with soap and water.” To this end, it clarified and unified the sanitation category ladder. From highest to lowest quality, sanitation can be: safely managed, basic, limited, unimproved, or non-existent, the latter including open defecation.

Let us take a closer look at each one of them and who in the world uses them:

Safely managed

The users of a safely managed sanitation system have an improved facility not shared with other households, allowing for safe disposal of excreta in situ or their transport and treatment offsite. These facilities allow the hygienic separation of excreta preventing them from coming in contact with people.

What is a safely managed facility? As in the case of access to water, the JMP clarifies a somewhat confusing term in terms of communication: improved facilities are those whose construction allows for the hygienic separation of human excreta, preventing them from coming in contact with people. Improved sanitation facilities include toilets connected to a sewer system or septic tank, protected latrines, such as ventilated improved pit latrines, pit latrines with slab, and composting toilets.

According to the JMP, between 2015 and 2020, the percentage of the world’s population with access to a safely managed service increased six points, from 47% to 54%, meaning that more than 4.2 billion people benefit from safely managed facilities. Rural areas are the least benefitted: only over 44% have this kind of facility, compared to over 61% in urban areas.

Basic

It is the use of improved sanitation facilities that are not shared with other households but do not allow the disposal of excreta in situ or their transport and treatment offsite.

In this case, there is virtually no evolution. In 2015, 25.7% of the population (1.9 billion) used this type of installation, while in 2020, it was just over 24%.

Limited

This term refers to the use of improved sanitation facilities shared between two or more households. This is the case of communal latrines in villages and cities built to prevent users from coming in contact with excreta. However, not all of them incorporate handwashing facilities.

According to the JMP, nearly 7.5% of the world’s population, around 580 million people in 2020, have this system.

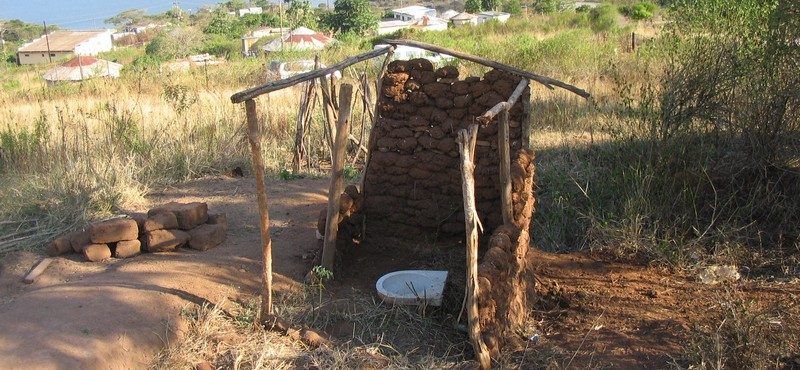

Unimproved

It implies using simple pit latrines without slab or platform, hanging, and bucket latrines. This type of sanitation does not guarantee health and often lacks hygienic handwashing facilities.

Around 616 million people, most of them in rural areas, used this type of precarious latrines in 2020.

Open defecation

It implies the lack of any sanitation facility. Human feces are left on fields, forests, water bodies, beaches or other spaces such as streets or open sewers. Feces generated in households that are wrapped or placed in containers for their subsequent disposal are also included in this definition.

In 2020, more than 5% of the population, almost 500 million, practiced open defecation in 55 countries. Nine out of ten lived in Central and South Asia (223 million) and sub-Saharan Africa (197 million). Although this group has experienced a significant reduction in the last few years (738 million in 2015), progress is still slow towards the total eradication of this scourge by 2030.

Eradicating open defecation is highly important to attaining gender equality and justice as stated in SDG 5. Unfortunately, women and girls are the ones who suffer most from its consequences as their safety and dignity are compromised. Many are assaulted while relieving themselves, and often, fear is enough to keep them out of school or hold back the need to urinate or defecate, leading to multiple bowel and urinary tract diseases.

The testimony of our projects

The projects we have developed all around the world during the last eleven years have brought sanitation to more than 300,000 people in 12 countries and have allowed us to see the direct relationship that always exists between lack of sanitation and poverty.

This is especially evident when it comes to open defecation. It is a very complex problem involving long-standing social and cultural factors. The projects in which we have specifically fought this practice have led us to verify these shortcomings in some of the most neglected regions of the world, such as Indonesia, Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, India, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Our experience in Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in Africa, has been particularly enriching. There, the collaboration with UNICEF, which began four years ago, has eradicated open defecation in the Sissili province by implementing the CLTS method, based on the empowerment of communities that, through self-awareness of the severe consequences of this practice, decide to abandon it and build their own latrines. There, our Manual for the construction of latrines and wells, a volume that compiles our accumulated experience in sanitation projects all around the world, established one of the working bases that are being followed by the Ministry of Water and Sanitation and the Ministry of Health to make the whole country free of open defecation.

A challenge as complex as it is essential

Achieving the sanitation targets of SDG 6 is one of the key concepts. It is the basis for many other development challenges, as it directly impacts public health, education, and the environment. We have to remember that, according to UNICEF, nearly 1,000 children die every day from diarrheal diseases linked to polluted drinking water, deficient sanitation, or poor hygiene practices.

And to people in vulnerable situations” refers to attending to the specific needs of “special cases”, such as refugee camps, detention centers, mass gatherings, and pilgrimages. ©Rabiul Hasan / icddr

Researchers from the World Resources Institute (WRI) claim that investing 1% of the GDP would solve the global water and sanitation problems. This is equivalent to $0.29 per person and day until 2030, a quantity that would be affordable assuming it were distributed proportionally to the per capita income of the Earth’s inhabitants. Never has such a small investment brought so many benefits.