Bryar, the protagonist of the documentary Tanjaro is Dying, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5, has spent his entire life by the Tanjaro River, located south of the city of Solimania, the capital of the Suleimaniya province in Iraqi Kurdistan. He still remembers with longing when the area was a beautiful and green tourist destination.

Tanjaro is Dying by Horen Gharib, micro-documentary finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

One war after another

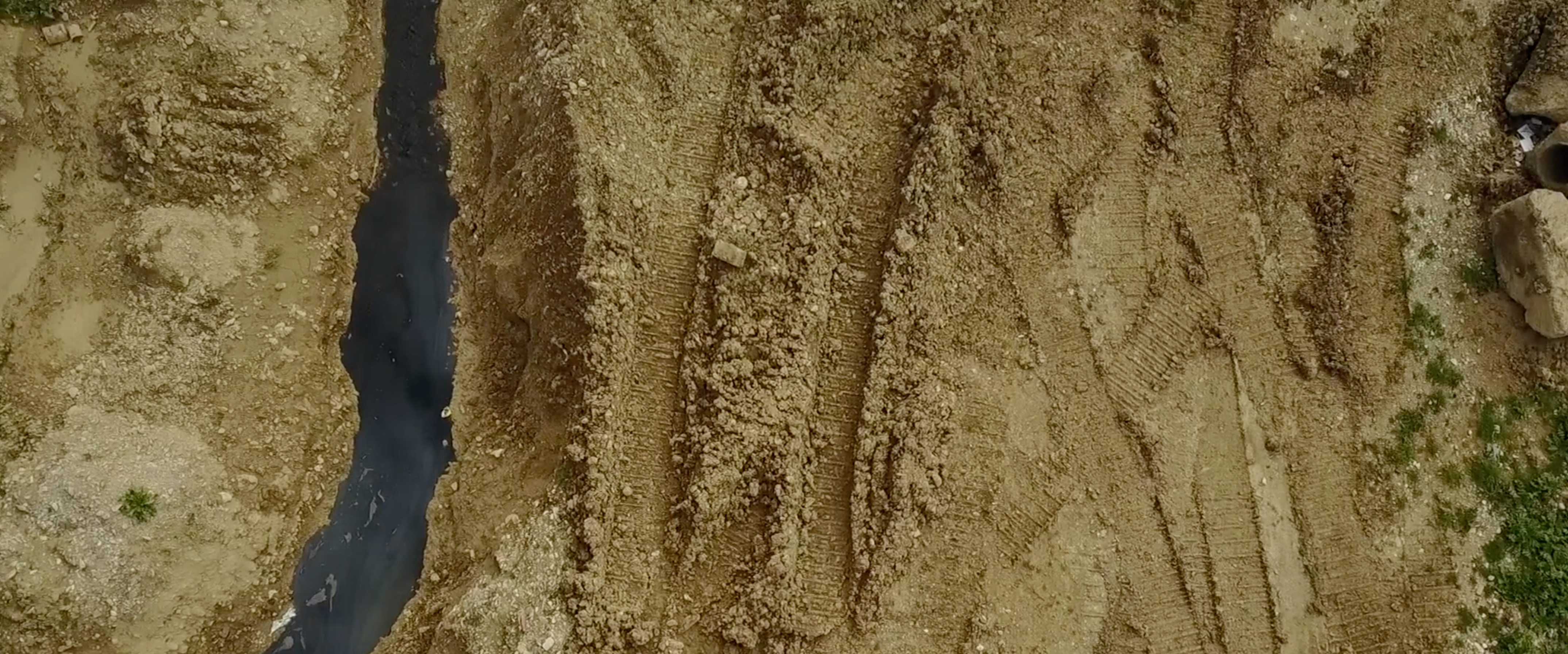

Before the 1990s, the government of the city treated wastewater and obtained compost for agriculture. Today the discharges go directly into the river untreated, as the facilities were looted and then sold after the Gulf War. The riverbed, south of the city, became an open sewer. This meant ruin for agriculture and most farmers had to migrate.

After the war, conflicts with the Kurds inhabiting the area flared up, and the following Iraq War, from 2003 to 2011, deepened the neglect of governance with regard to sanitation.

After the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in late 2011, many Syrian Kurds, especially those living in the north of the country, migrated to northern Iraq. Today, there are about one million internally displaced people and asylum seekers in Iraqi Kurdistan. 49% are in Erbil, 30% in Duhok and 21% in Solimania, worsening the demographic situation and health needs.

The riverbed, south of the city, became an open sewer.

From river to sewer

The uncontrolled growth of the city, which reached 740,000 inhabitants in 2020, eventually destroyed life in the former freshwater paradise that was the Tanjaro. Several industrial zones and oil refineries also discharge their chemical waste into the river. Specialists from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at Sulaymaniyah University have found pollutants such as mercury, lead, cadmium and nitrates in the river water.

The uncontrolled growth of the city, which reached 740,000 inhabitants in 2020, eventually destroyed life in the former freshwater paradise.

The little agriculture that survives uses this highly polluted water to irrigate crops and water livestock. The local population has no way to avoid the contamination: it comes to them through their drinking water and through the rest of the food chain.

“Ididn’t suffer from any disease before. Now I have spots on my hands. Also, most of the people in the area have contracted diseases like asthma, tuberculosis or different types of cancer.” Bryar’s testimony confirms the studies of the Sulaymaniyah Provincial Council’s Health and Environment Committee that show the absolute lack of control of Solimania’s wastewater.

Downstream, the pollution is advancing through the waterways of Iraqi Kurdistan and is already reaching the main sources of drinking water for locals in the Kalar areas. The Tanjaro River flows into the Darbandikhan Dam, where it joins the Sirwan River. Both form the Diyala River which is a tributary of the Tigris, the great river of Mesopotamia that together with the Euphrates gives life to all of Iraq.

Downstream, the pollution is advancing through the waterways of Iraqi Kurdistan and is already reaching the main sources of drinking water for locals in the Kalar areas.

The administration does little to solve the problem. Nor does it have the means to do so effectively. Water and sanitation strategies barely maintain pre-1990 infrastructures that are badly deteriorated by wars and lack of maintenance.

Today the discharges go directly into the river untreated, as the facilities were looted and then sold after the Gulf War.

With the deterioration of people’s health on the rise, the Sulaymaniyah Provincial Council has carried out a study on water quality and the authorities are expected to take action, but so far no action is forthcoming.

The destruction of the Tanjaro River ecosystem shows that all is lost when water is polluted.

An abandonment that must end

The case of the Tanjaro River is one of many rivers in the world that die abandoned to sewage and garbage. And with them, human activities die and people suffer. A sick river drives out the life around it. Historically, little data has been collected on the global state of freshwater ecosystems. To remedy this gap, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has turned to observational technologies to track, over extended periods of time, the extent to which freshwater ecosystems are changing. Researchers have studied more than 75,000 bodies of water in 89 countries and found that more than 40% were severely polluted. The result is that more than 3 billion people are at risk of disease because the water quality of their rivers, lakes and aquifers is unknown.

In the already short period that separates us from the SDGs by 2030, saving rivers must be an international priority. As some NGOs point out, less than 0.5% of the military spending on the Iraq War could have reformed sanitation and water supply facilities throughout the country.