On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared Covid-19 a pandemic. The alarm, which had already spread in most countries, made the last report published by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) go almost unnoticed. It was presented the day before at a press conference by UN Secretary-General, António Guterres and the WMO Secretary-General, Petteri Taalas. The document compiles the consequences of global warming on the health of people, marine life and the main ecosystems of the planet during 2019.

At the end of last year, an estimated 22.2 million people in Africa suffered once again from famines similar to the ones experienced during the prolonged and terrible drought of 2016/17.© Mohammad Yeasir Sarowat / World Meteorological Organization

The report does not bring good news with regard to the evolution of climate change and its forecasts for the future. However, the world’s attention in March was focused on the immediate health threat and the work posed by the pandemic, with the evils with which climate can harm us coming second in the media. It is something that continues to seem a distant threat even though virtually all of humanity is already suffering the consequences of global warming.

2019, a bad climate year

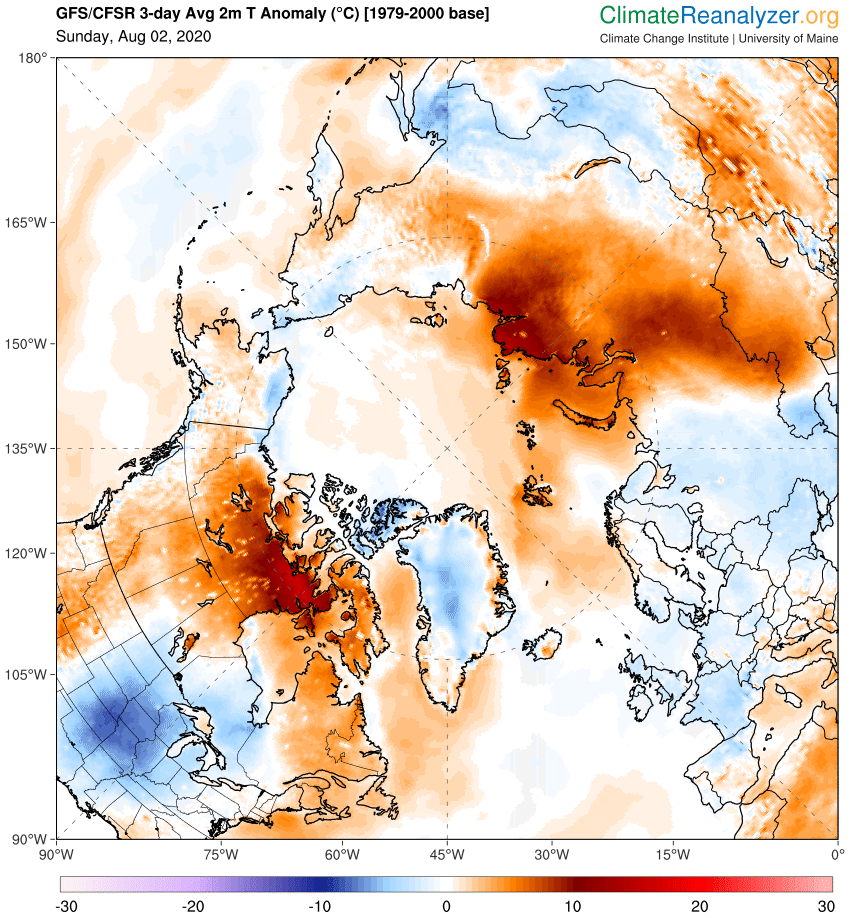

Temperature anomaly in Arctic territories © ClimateReanalyzer

The WMO report points out that 2019 ended with an average temperature in the planet of 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels, a value only exceeded by the 2016 record. Starting in the 1980s, every new decade has been warmer than all previous ones since 1850.

The lethal power of heat waves is now becoming a recurring issue in the world’s summers. In Western Europe, heat caused hundreds of additional deaths and in Australia, devastating fires spread ash all around the world and caused a peak in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

Record temperatures in the Arctic and Antarctic melted the ice to unprecedented levels. In the Northern hemisphere, this problem was aggravated by the fact that summer came after the hottest month of January ever recorded. This year is also expected to be the year with the least amount of ice in the Arctic, and the WMO confirms that this polar region is warming at twice the rate of the global average.

The loss of polar ice favors sea level rise caused by thermal expansion of seawater, which is also growing. This increases the risk of floods in many coastal regions and islands and may cause their lower elevations to be permanently submerged.

Taalas stated that “a new global annual temperature record is likely to occur in the next five years. It is only a matter of time.” And Guterres warned of the great problem we face in the fight against climate change: “We are currently far from meeting the objectives of the Paris Agreement to limit temperature increases to 1.5 or 2°C.”

2020 confirms the trend

This year is expected to be the year with the least amount of ice in the Arctic. © Karolin Eichler / World Meteorological Organization / Deutscher Wetterdienst

Since last March, when all governments enacted lockdown measures because of Covid-19, bad news about the climate crisis has not ceased to arrive, providing continuity to what happened in 2019 and confirming the dark predictions of the WMO.

What is most alarming, in terms of reducing greenhouse gases, is that many Arctic territories, especially Siberia, have been recording temperatures well above average since winter. In June, the prolonged Siberian heat wave and the increase of forest fires in the region raised the alarm: in the Siberian city of Verjoyansk, north of the Arctic Circle (latitude 67ºN), the highest temperature ever, 38ºC, was recorded this year. That same day, in the city of Seville, in the south of the Iberian Peninsula (latitude 37ºN) the thermometer reached a maximum temperature of 37ºC.

Scientists point out that the melting of the permafrost, which started during the 2019/20 “warm winter” and the greater heat absorption experienced by the ground with no snow or ice have possibly caused an anomalous warming in spring and this effect has shifted to this summer. Should this hypothesis be confirmed, the Siberian Arctic zone could experience a positive feedback process (more heat causes less ice, which in turn produces more heat.) In addition to the stability problems of many Siberian buildings, built on this frozen layer, and the release of microorganisms buried in its mud, one of the greatest concerns of the melting of the permafrost is the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and, above all, methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas that is more harmful than carbon dioxide.

Health: climate, as well as the pandemic

The WMO report focuses on projected impacts of meteorology and climate on the health of people, food security, migrations, ecosystems and marine life.

Besides the additional deaths by hyperthermia and dehydration caused by the heat waves that are affecting children and the elderly in the poorest areas, changes in climate conditions facilitate the spread of tropical diseases. The most obvious is dengue fever, which spreads through Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.The report states that the amount of dengue fever cases greatly increased all around the world in 2019.

In addition to Covid-19, the heat waves affecting tropical countries this summer are hampering the fight against pandemics such as malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis. Likewise, water-borne diseases and those caused by the lack of sanitation and hygiene, such as diarrhea, malaria and cholera, increase with high temperatures.

In terms of food security, the UN Secretary-General noted that, after a decade of constant reduction, hunger is on the rise: more than 820 million people suffered from hunger in 2018. In 2019 droughts, along with violence, significantly worsened food security in many African countries. At the end of last year, an estimated 22.2 million people in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan suffered once again from famines similar to the ones experienced during the prolonged and terrible drought of 2016/17.

Hurricanes, floods and fires above average

Cyclone Idai. Mozambique. © World Vision

In 2019, tropical cyclone activity was above average in all oceans. There were 72 tropical cyclones in the Northern hemisphere. The 2018/2019 season in the Southern hemisphere also exceeded average records, with 27 cyclones forming.

The most exceptional was Cyclone Idai, which made landfall in Mozambique on the 15th March. It was one of the most powerful ever seen in the Eastern coast of Africa. It killed 1,000 people and washed away some 780,000 hectares of crops in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi, exacerbating the endemic food insecurity in these countries and displacing more than 180,000 people. The We Are Water Foundation collaborated with World Vision in an emergency aid project in the region, with the aim of covering the most basic hygienic needs of those affected by means of water filters and hygiene kits.

The Asian monsoon started late, but its floods caused more than 2,200 deaths in India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar. In the US, total economic losses due to floods in 2019 were estimated at US$20 billion and severe flooding in northern Argentina and Uruguay caused estimated losses of US$ 2.5 billion.

In addition to the Arctic regions (Siberia, Alaska and Canada), forest fires in 2019 were above average in the jungle regions of Indonesia and the Brazilian Amazon and were particularly devastating in Bolivia and Venezuela, with the consequent harmful release of CO2.

Fires in Australia, which occurred at the end of 2019 and continued into January 2020, burned seven million hectares and caused dozens of deaths, destroying more than 2,000 homes.

Coronavirus and climate crisis. What can we learn from them?

When the WHO officially declared the pandemic, its Director General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, stated his concern about the lack of action by governments in the fight to prevent contagion. That same concern about inaction had been expressed two days earlier by António Guterres at the UN in reference to the climate crisis: “Covid-19 is a disease that we hope will be temporary, but climate change has been there for many years and will stay for decades and requires continuous action. We need to prove that cooperation and international action are the only way to obtain significant results.”

The climate crisis is there and will get worse if we do not stop it. We need to avoid the common human reaction that tends to ignore problems that are complex and uncertain in the long term. Inaction is unsustainable and takes us to a future of ruin for humanity. Governments, scientists and the media are obliged to integrate educational aspects into scientific information, to explain why changes are necessary and to show solutions based on the tangible and achievable collective benefit of solidarity.

Coronavirus is showing us that the disease of one person is the disease of all, just as health is. The spread of the infection has proven that the delay in responding in a matter of days or weeks makes a dramatic difference. The same principle can be applied to the climate crisis and, although the time scale is different, the consequences can be much more severe for everyone. Let us not postpone action for the long term, let us act now.