The word wadi is an Arabic term used to designate a type of riverbed that holds water only in the rainy season; the rest of the year, it remains dry. Almost all the wadis on the east coast of North Africa have a hard and not very porous stony bed that absorbs little water. When it rains, runoff is immediate and violent in the case of heavy downpours.

But what happened in the Darnah wadi, which runs through the heart of the city of Derna before flowing into the sea, is not even remembered by the local elders. On September 10, storm Daniel, which a few days earlier had devastated Greece, struck with brutal intensity. It generated more than 414 liters of rain in 24 hours in Al-Bayda, a town west of Derna, an amount never recorded before and more than it rains in the area in a year (about 350 liters).

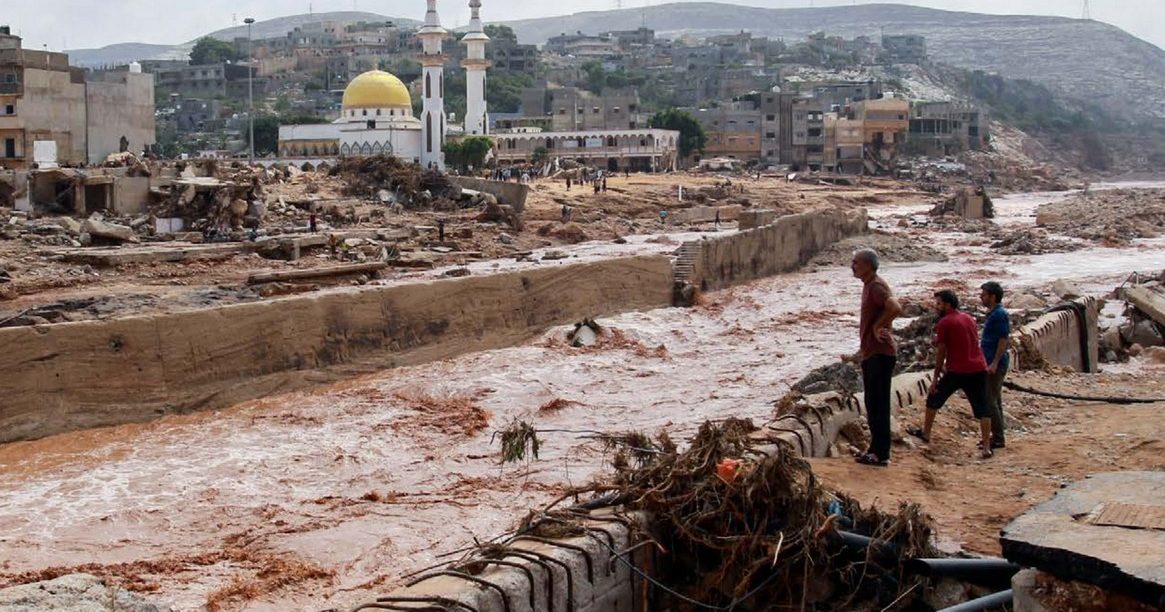

The Darah wadi after the flood. The tragedy in Libya shows the lethal vulnerability of the combination of a cyclone and the neglect of water facilities. © Libyan Red Crescent

There are two dams in the Darnah wadi: one on the southern outskirts of the city, the Al Bilad dam, with a capacity of 1.5 million m3, and the other about 20 km upstream in the mountains, the Abu Mansour dam, with a capacity of 22.5 million m3. As a result of the sudden increase in water, which exceeded the reservoir’s capacity, the Abu Mansour dam collapsed, and the water swept down the wadi until it reached the Al Bilad dam, which also burst.

Entire neighborhoods wiped off the map

The flood in Derna was devastating. Most of the houses in the neighborhoods along the wadi were washed away, and in some areas, the water was more than five meters high, so people on the second floors of the buildings drowned or were swept out to sea.

Dam failure was one of the main factors contributing to the catastrophe in Libya. © OCHA

The estimate of casualties is not yet definitive, and it will be some time before the death toll is confirmed, as the sea continued to dump bodies on the beaches ten days after the disaster. On September 20, the UN estimated 11,300 dead and 10,000 missing; more than 40,000 people have lost their homes, and 70% of the road, water supply, and sanitation infrastructures have been destroyed. Displaced people are also numbering in the tens of thousands, and according to UNICEF, 300,000 children need assistance.

The violence of Daniel

A few days earlier, the storm named Daniel had been an unprecedented phenomenon in Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria, causing dozens of deaths and thousands of people displaced from their homes. In central Greece, September 5 saw the highest rainfall record since meteorological observatories have been in operation.

A few days earlier, the storm named Daniel had been an unprecedented phenomenon in Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria ©Makis Theodorou

The World Meteorological Organization described Daniel as a “medicane,” a hybrid phenomenon that combines characteristics of a tropical cyclone and a mid-latitude storm. It is caused by the jet stream that brings cold air 7-12 km above sea level, which, together with the high water temperature (the Mediterranean reached surface temperatures of 30ºC this July), causes a very powerful depression whose dynamics resemble Caribbean cyclones.

Neglect, more lethal than a cyclone

However, dam failure was one of the main factors contributing to the catastrophe in Libya. A first analysis indicates that the deterioration of the dams and the spillways of the reservoirs, clogged after years of not being cleaned, were the leading causes of the collapse of the structures. According to the deputy mayor of Derna, the facilities had not been maintained since 2002.

Underlying this negligence is a chaotic and corrupt political context incapable of dealing with an endemic economic crisis, the fight against terrorism, and migration mafias. After the fall of Muammar El-Qaddafi in 2011, the country was embroiled in a bloody civil war until 2020. Although the two sides officially signed a permanent ceasefire and agreed to the departure of foreign troops, the aftermath of the conflict continues to block any effective governance.

The Presidential Council of the transitional government has ordered an investigation to uncover possible negligence in the catastrophe. Still, the affected population faces the threat of disease following the accumulation of dead bodies and the destruction of sanitation and drinking water supply systems.

Weather warnings, more necessary than ever

The tragedy in Derna is a painful reminder of the importance of adequate preparation and effective response in times of crisis. The need for functional weather services and early warning systems has never been more evident. A few minutes can save thousands of lives.

In 2016, we attended the 13th Forum International de la Météo et du Climat (FMI), organized by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in Paris with a representation of Spanish meteorologists. There, the development and definitive implementation of an international warning system was advocated. The plan has not yet materialized, but the good news came at the last COP27 when the project was discussed and named the Global Early Warning Initiative. Finally drafted by the WMO, the plan aims to protect all the Earth’s inhabitants by installing systems that provide early warning of dangerous extreme events. The project has the highest priority in WMO’s Strategic Plan for 2024-2027, and hopefully, this summer’s Mediterranean disasters will accelerate it.

The technology exists and must be shared. The climate crisis also forces us to reconsider the map of exposure to disasters and to look at it from the perspective of vulnerability, a factor that is on the rise. Defenselessness to weather is a new challenge of the climate crisis that we must face.