How many people live and work in flood-prone territories?

Violent weather phenomena that have recently devastated various regions of the world have brought this question to the forefront for governments, insurance companies, and international aid organizations. The World Bank estimates that 1.47 billion people are directly exposed to flood risks of over 0.15 meters at least once every 100 years. Of these, 587 million live in poverty — a figure that continues to rise every year.

This issue was central to discussions at COP29 in Baku, where it was a critical factor in assessing damages and financial compensation for developing countries, which are the most vulnerable to such disasters.

Extreme weather events with torrential rains are increasing. © Sung Jin Yoon/WMO

When Flooding Strikes Industrialized Nations

Despite the alarming global risk figures, public concern over extreme weather events often intensifies when developed countries are affected. This happened in the summer of 2021 when Storm Bernd flooded vast areas of Germany, causing 165 deaths. Weeks later, Hurricane Ida became the second most intense and destructive storm in Louisiana, USA, surpassed only by Katrina in 2005. Economic losses amounted to at least $50.1 billion.

That summer, international media highlighted how these floods coincided with IPCC reports’ predictions, which warned of increased extreme events due to climate change. However, subsequent analyses revealed that victims and damage were concentrated in urbanized areas topographically prone to flooding during anomalous river swells. Urban planning had disregarded this geographical factor.

Despite the alarming global risk figures, public concern over extreme weather events often intensifies when developed countries are affected. © gankogroup/ vecteezy/

Valencia: A Case Study of Exposure

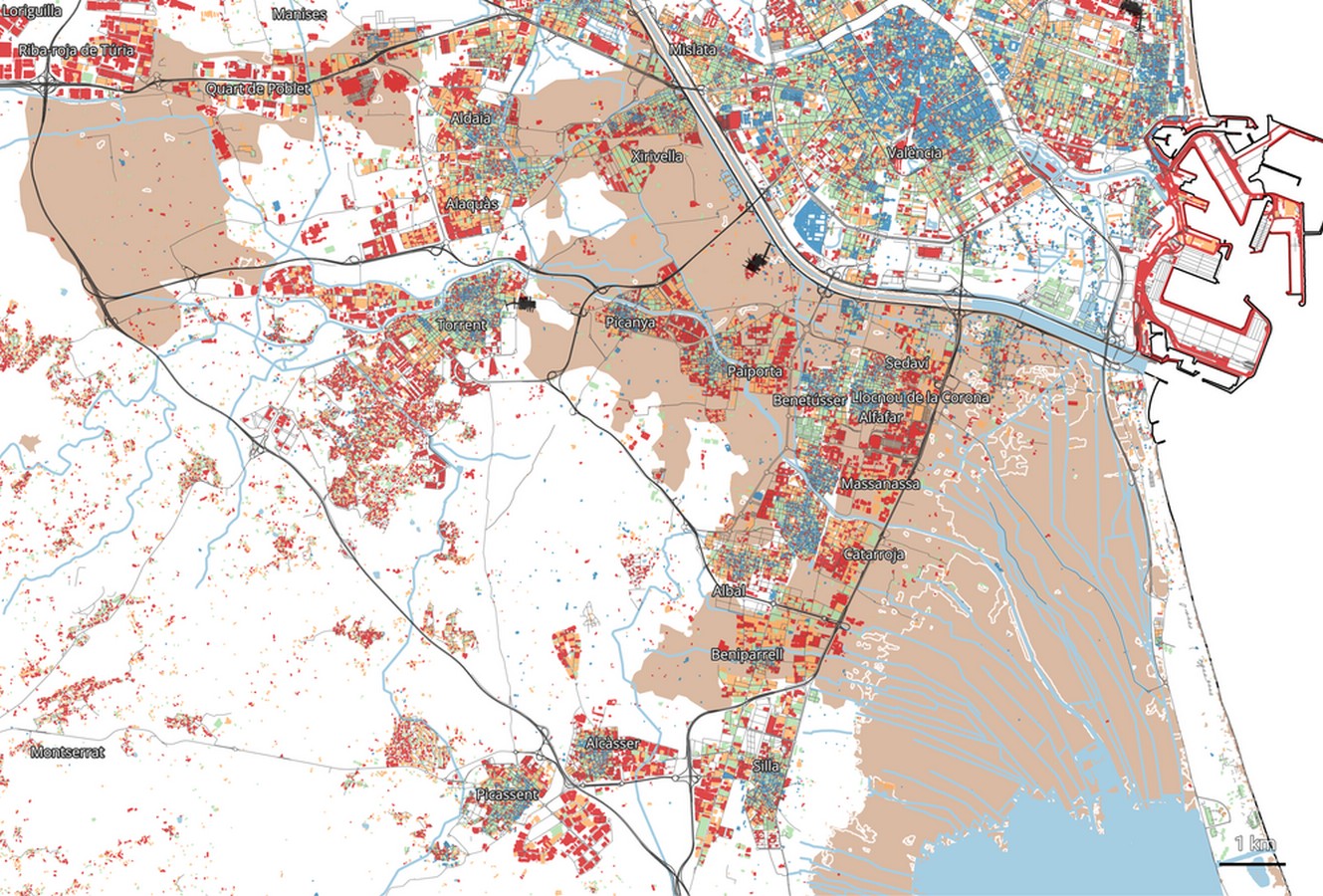

On October 29, an upper-level low-pressure system (known in Spain as a DANA, or Isolated Depression at High Levels) triggered exceptional rainfall in the hydrographic basins south of Valencia. Satellite data from the Copernicus program showed that the flooding affected over 15,633 hectares. More than 220 people died, and about 190,000 were impacted. According to Datadista, floodwaters damaged 130,000 homes and blocked 3,249 kilometres of streets, sweeping away tens of thousands of vehicles. The losses mark Spain’s most costly natural disaster and one of Europe’s largest.

Significantly, most of the affected homes had been built since 2003 in areas historically known to be flood-prone since the 18th century.

Map of October 29, 2024, flood effects in Valencia, created by Datadista using data from Spain’s Geographic Institute, Copernicus satellite images, and cadastral records. Brown represents flooded areas; red shows buildings constructed after 2000.

Natural Drainage Alteration Worsens Disasters

Asphalt and concrete seal the soil in highly urbanised areas, diverting water into hydrological channels that often overflow. Furthermore, roads, highways, and railways with insufficient or poorly designed drainage systems—or those blocked by vegetation or debris—act as barriers that worsen flooding.

Another contributing factor is the growth of motor vehicle fleets. In Valencia, dramatic images of cars and trucks swept away and clogging streets and underpasses went viral on social media, highlighting that exposure to pluvial disasters is largely anthropogenic.

Poor Countries Bear the Greatest Burden

The extreme vulnerability of exposed populations exacerbates damages. Poorer regions face endemic risks; in Sub-Saharan Africa, 71 million inhabitants of flood-prone areas live in extreme poverty. Disasters are recurrent in informal settlements, such as the one on the slopes of Sugar Loaf Mountain in Freetown, Sierra Leone, home to one of the world’s largest slums. In 2017, after three days of torrential rain, landslides swept away hillside shacks, killing over 500 people and leaving more than 3,000 homeless.

This year, tragic floods also struck Nairobi’s slums—Kibera, Mathare, and Mukuru—causing 188 deaths and destroying over 33,000 shacks. Floodwaters and landslides temporarily displaced nearly 200,000 people.

Rethinking Risk Requires Reducing Exposure

In the Pacific Ocean, typhoons devastate large parts of the Philippines annually. In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan claimed over 6,300 lives and displaced more than four million. Winds of up to 235 km/h swept seawater into flat coastal areas, destroying homes for over 4.3 million people in Leyte and Samar provinces.

Haiyan’s devastation—where we intertwined with an emergency responseproject—forced the Philippine government to rethink risk, exposure, and vulnerability factors. This has been one reason why successive typhoons, such as Trami in October, have caused less damage than anticipated.

Actions taken in the Philippines can serve as a universal roadmap for combating such disasters:

- Resettlements to relocate people out of flood-prone areas.

- Construction of sturdier housing based on resilience studies.

- Restoration of natural barriers, such as reforestation of riverbanks and coasts.

- Early warning systems, like the PhilAWARE, have saved countless lives.

- Community disaster management training, empowering local leadership and risk management programs.

With climate change, floods are becoming more frequent. Local historical precipitation records will be repeated globally, like Valencia’s (771 l/m² in 24 hours in Turís). Rising sea levels have increased coastal flooding in the Pacific sevenfold over the past decade. The latest IPCC report (AR6) predictions are being realized, with even more violent phenomena than anticipated.

However, in flood cases, negligent land management causes more harm. In addition to mitigating climate change, we must reduce disaster exposure for a constantly growing population. Climate models predict that by 2050, 340 million people will live in areas with annual coastal flood risks, including urbanized zones without adequate infrastructure.

The adaptation challenge is enormous and disproportionately costly for poor economies. This issue has been prominent in COP29 discussions, as it directly impacts national adaptation plans (NAPs), which depend financially on agreed funding. Wealthy nations will allocate $300 billion annually starting in 2035. Let’s hope it will be enough.

In the Pacific Ocean, typhoons devastate large parts of the Philippines annually. © Erik de Castro – Reuters/ Mans Unides