In 1828, a grandiose concept was proposed: connecting the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean through an 82-kilometer navigable canal across the Panamanian isthmus. While technically feasible, the project faced significant hurdles, such as excessive costs, political instability, and uncertainty regarding its complex operation, which deterred potential investors.

The Panama Canal allows large cargo ships to save thousands of miles of navigation between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. © freepik

Enormous Savings in Time and Fuel

Nevertheless, in 1869, the inauguration of the Suez Canal altered the landscape significantly, prompting numerous major construction firms to view the idea as both feasible and economically lucrative. The demand for international shipping had surged, presenting compelling statistics: merchant clippers traversing the Gold Route from New York to San Francisco stood to save 7,872 miles by avoiding rounding Cape Horn; coal tankers voyaging from the US East Coast to Japan would enjoy a 3,000-mile reduction in distance; and a banana vessel journeying from Ecuador to Europe could slash over 5,000 miles off its route.

Following a series of political upheavals, corruption scandals, malaria outbreaks, and even an earthquake, Ferdinand de Lesseps, renowned for his work on the Suez Canal, initiated construction in 1881. However, his company faced bankruptcy, leading French engineer Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla to take over the project. By this time, Panama had gained independence from Colombia. In 1903, the new Panamanian government ceded perpetual rights to the canal to the United States, along with a significant swath of land spanning eight kilometers on each side. In exchange, the US paid $10 million upfront and agreed to an annual rent of $250,000.

The Panama Canal was officially opened on August 15, 1914, with the steamship Ancon leading the inaugural passage. Since then, its traffic has consistently grown, occasionally surpassing the Suez Canal’s, particularly during the two world wars. However, on December 31, 1999, ownership of the Canal shifted entirely from the United States to the Republic of Panama.

A Canal That Requires Fresh Water

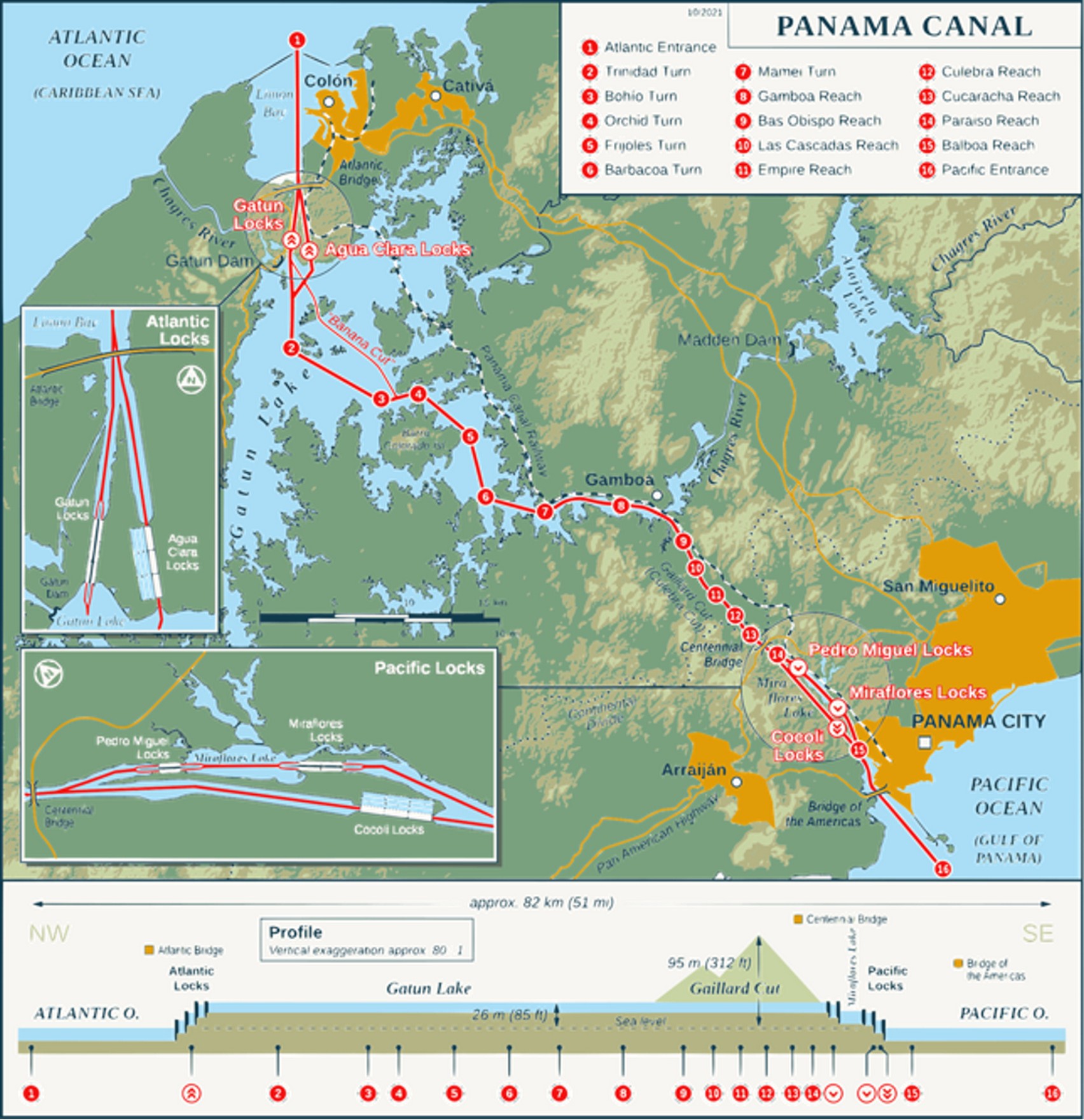

The primary challenge of the project was connecting two bodies of water with varying elevations. The Caribbean coast sits approximately 26 meters higher than the Pacific Ocean. To overcome this difference, an 82-kilometer route was devised, incorporating a series of five locks. These locks facilitate the raising and lowering of ships by filling and emptying basins measuring 305 meters in length, 33.5 meters in width, and 26 meters in depth. These dimensions dictate the maximum size of ships capable of traversing the canal.

Freshwater from the basin’s rivers was used to fill the locks, as seawater would have been costly to pump, and the salt content could have damaged the sluice gate mechanisms and affected the aquifers. One of the world’s largest artificial lakes, Gatun, was constructed to accomplish this. Gatun serves as a crucial component of the canal’s intricate lock system.

Infographic map of the Panama © Thomas Römer/OpenStreetMap data, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Climate Crisis, An Unexpected Factor

The unusual drought gripping Central America, the likes of which haven’t been seen in 110 years, is disrupting the operation of the massive infrastructure.

In 2023, the occurrence of El Niño exacerbated this situation. El Niño is a cyclical phenomenon marked by atypical warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean waters, particularly in the equatorial region. It’s an erratic event, manifesting every two to seven years with varying intensity, and its origins remain somewhat elusive to scientists. However, what is evident is its profound impact on global climate patterns, particularly in the Caribbean, where reduced rainfall is observed.

El Niño exacerbates the impacts of climate change. In 2023, Panama experienced a 30% reduction in rainfall compared to the average, marking it the second driest year in the history of the river basin that supplies freshwater to the canal. Consequently, the water system has only managed to store 50% of the volume required to meet the projected demand for the year. Gatun Lake, ideally maintaining a surface elevation of approximately 27 meters above sea level, was recorded at barely above 24 meters in January.

There’s insufficient water to facilitate the standard operation of the locks. Although the canal’s reservoirs have a capacity of 1,857 cubic hectometers, only around 900 cubic hectometers are currently stored. Furthermore, the operation of the locks demands a significant amount of water. For instance, each time a ship is lifted from the Pacific into Gatun Lake, it consumes the equivalent of 70 Olympic-size swimming pools. Despite the substantial $5 billion investment made five years ago to enable the passage of larger vessels, the influence of climate change has introduced unexpected challenges for everyone involved.

Economic Losses and Changes in International Logistics

The Panama Canal lock system needs adequate water levels to function. © artes2franco / Pixabay

Typically, the Panama Canal accommodates around 38 ships per day, transporting goods valued at approximately USD 270 billion annually. However, last August, a traffic jam of 134 ships occurred due to the drought. Despite this challenge, in 2023, over 14,000 ships traversed the canal, facilitating 3% of global maritime trade. Presently, the Canal Authority has limited passage to only 20 ships, and there are concerns that traffic may further decline by April. Forecasts from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) suggest that the effects of El Niño, including the drought, will persist throughout the year.

The Canal Authority predicts losses of up to 648 million euros this year. The average toll for crossing the Canal stands at approximately $45,000. However, many ships save up to ten times that amount by avoiding the journey around Cape Horn, which increases sailing time by 55%.

On another note, global warming is paving the way for an unforeseen new sea route: the Arctic. Melting ice progressively enables conventional cargo ships to pass through northern Alaska and Canada, providing a direct route between Asia and Europe.

A More Deglobalized Future?

The crisis in the Middle East and the recent attacks by the Houthis on merchant ships crossing the Gulf of Aden are affecting traffic between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. As a result, the two main arteries of global maritime transportation are congested. This situation has prompted many observers to question the model of international maritime trade that underpins today’s economic globalization: transporting goods over vast distances. This model has contributed to emissions and promotes water waste due to the water footprint of trade. Climate change may necessitate a reevaluation of value chains, pushing for the relocation of production centers closer to consumers and expediting the transformation of maritime trade processes.