In biogeography, moorlands are defined as intertropical alpine ecosystems classified as mountain scrub grasslands. They are found at altitudes between 2,900 and 4,500 meters, which is the average of the perpetual snow line. There are moorlands on all continents, but the best known is the Sumapaz, in Colombia, considered the largest and most crucial producer of freshwater in the world.

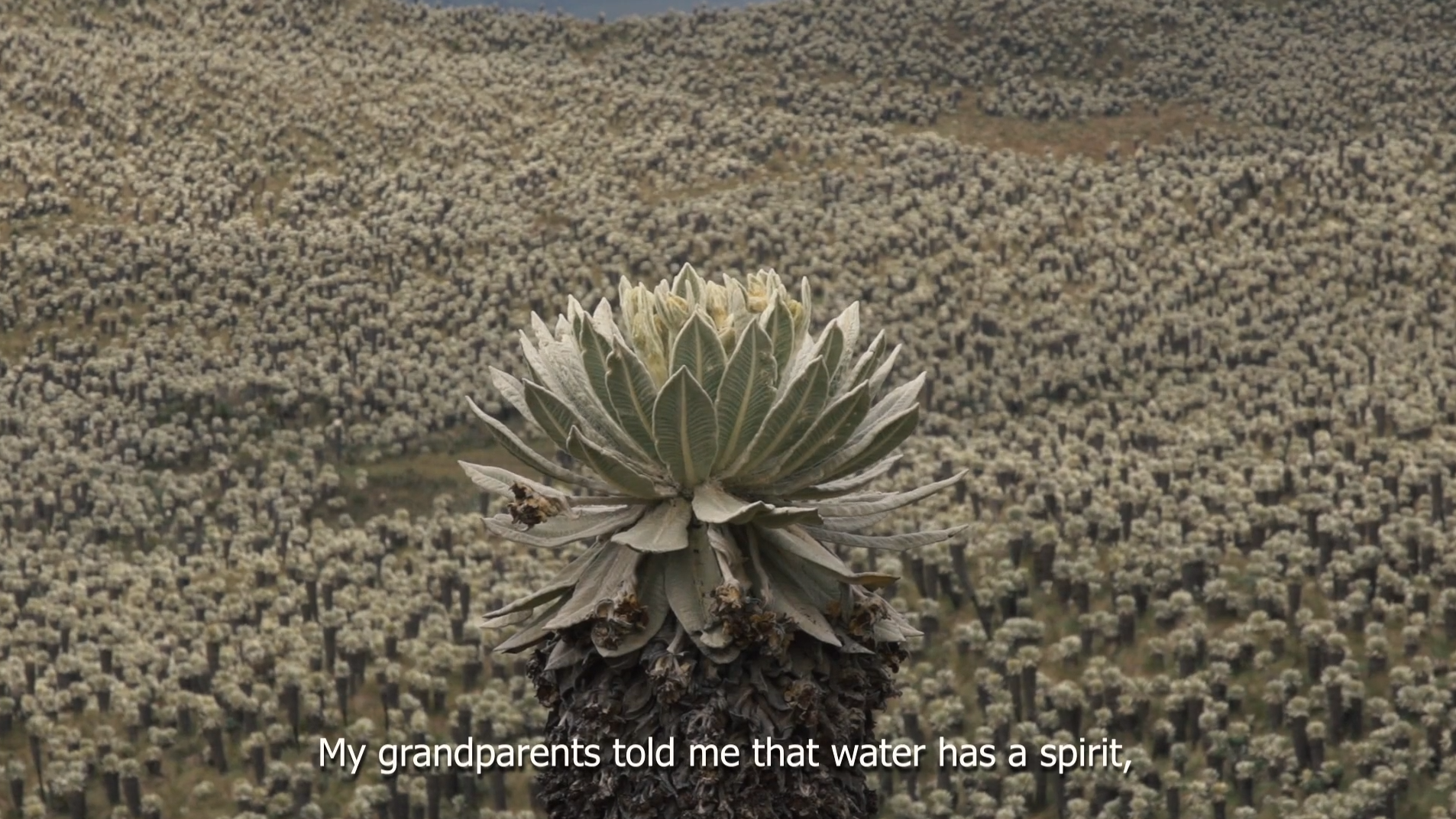

From a water perspective, moorlands are significant reserves of pristine water and some of the critical ecosystems for environmental balance downstream. On the other hand, moorlands are home to great cultural wealth: their communities have forged an intense and profound relationship with nature and the water they provide. In El espíritu del agua (The spirit of water), Diana Moreno, finalist of the We Art Water Film Festival 5, shows the relationship that has existed and still exists in the Sumapaz moorland.

The moorlands are home to pristine water and natural balance.

A moorland damaged for decades

But, since the 1950s, the moorland has been at risk. At the time, violent clashes between the Conservative and Liberal parties caused hundreds of peasant families to flee, finding refuge in the highlands of the moorland and building settlements that have survived to this day. Intending to protect the ecosystem, the Colombian government established the Sumapaz National Natural Park in 1977, restricting access to the area. But in the 1980s, FARC guerrillas set up their operational base against the capital, Bogotá, in the national park.

The FARC and the Colombian army engaged in constant clashes, affecting farmers and damaging the ecosystem. After the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC, Sumapaz ceased to be a battlefield, leaving the door open to a hopeful recovery.

El espíritu del agua (The spirit of water), a short film by Diana Moreno, finalist of the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

However, the moorland continues to be at risk. Cattle ranching, intensive monocultures, land burning, mining, and mass tourism threaten to cut short the recovery of the park and its water.

Sumapaz is an example of the paradox of water resources in Colombia, one of the countries with the highest theoretical water availability per inhabitant. According to the World Bank, each Colombian has almost 45,000 cubic meters of freshwater per year. Compared to Sweden, with 18,300, Spain with 2,400, and India, with only 1,519, it gives an idea of the enormous water potential of the Andean country. Still, deficiencies in distribution and management prevent this wealth from reaching the entire population.

Today, Sumapaz benefits from one of the Colombian government’s priorities, preserving water. To this end, it extends the protection of moorlands and watersheds and improves supply and sanitation based on the National Policy for the Integral Management of Water Resources. This effort must be supported and extended worldwide.

In biogeography, moorlands are defined as intertropical alpine ecosystems classified as mountain scrub grasslands.

A sacred place for the indigenous people, a sacred place for the world

Beyond its natural capital, Sumapaz is of immeasurable cultural value. For the indigenous Muisca and Sutagaos, it was a sacred place that was their home before the arrival of the Spaniards. This spiritual relationship with the moorland is reflected in the short film in the narrator’s voice, a girl who symbolizes the new generation of “the guardians of water,” which has begun to understand the voices of their territory and the legacy of their ancestors.

For the indigenous Muisca and Sutagaos, it was a sacred place that was their home.

With environmental destruction, we lose water and impoverish life and the environment; we also lose collective memory and culture. And safeguarding culture through education and government support is an effective tool for action and brings resilience to communities. We saw this in our project Ancestral culture to save the water of Lake Titicaca, and it is evident that this principle is the roadmap to environmental disasters such as those of the Aral Sea, Lake Poopó, Lake Titicaca, or Lake Urmia.

With the recovery of their culture, young people will perpetuate the millenary knowledge that is part of the identity of their land. And young people are the guarantee of the sustainability and life of each of the ecosystems that are part of the historical heritage of all humanity.