The sustainability of sanitation is very differently understood around the world depending on its availability and use. In industrialized countries, those who know what “sanitation” means associate it with infrastructure-based services (sewers, drains and treatment plants) and technologies for the disposal of unhealthy waste. For these people the hygienic function of the system is obvious, most of them have never seen a sewer and forget waste every time the toilet is flushed or the laundry sink is drained. According to the WHO, in 2015 1.9 billion people, 27% of the world’s population, enjoyed this type of sanitation based on the full cycle of water.

The economically rich world does not consider the sustainability of sanitation in terms of having it or not. It considers it in terms of greater or lesser economic benefit and in terms of non-aggression to the environment. In general sustainability in the industrialized world is now based on the postulates of circular economy, which will guarantee the generation of value from waste using renewable energies and will keep the waters of rivers, aquifers and seas unaltered.

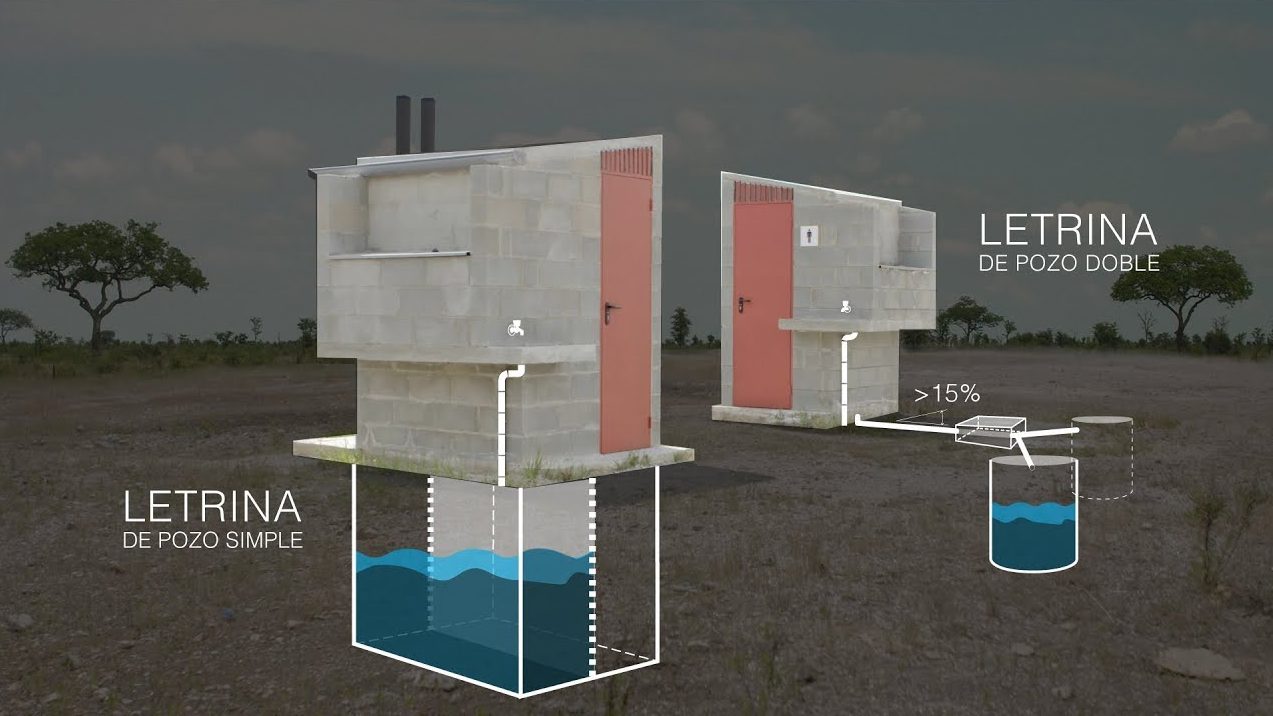

There is another world without sewers or treatment plants. It is the world of latrines, septic tanks and cesspools, whose proper functioning allows users to benefit from a basic hygienic rule: not to come in contact with their feces. These are the ones who, according to UN Water, have “safely managed” sanitation, which is not shared with other households and where excreta are either disposed of on site or transported and treated off site using flushing siphon systems or efficiently functioning composting toilets. In 2017 there were about 3.475 billion, 45% of the population, including the privileged ones of the economically strong world who use sewers and treatment plants.

Public toilet in the shanty town of Ciudad Pachacutec, Ventanilla District, El Callao Province, Peru. © Monica Tijero / World Bank

Those who do not have safe sanitation

The rest of the population, 55% of the planet, some 4.247 billion in 2017, lack safely managed sanitation. This includes those who cannot ensure the avoidance of contact with their feces or those who lack efficient waste disposal systems, or who have to travel far from home to use the latrines. Among these are those who defecate in the open, a group which, according to UN Water, reached 695 million people, 8.92% of the world’s population in 2017. In 2015, according to the WHO, they were 892 million; there has been an improvement, but the SDG 6, “Clean water and sanitation”, still seems very hard to reach by 2030.

Those who defecate in the open do so in the bush or in surface water; of these, 80 million are city dwellers that leave their feces in the street or in open sewers. Most of those who live in rural areas have inherited this habit from their ancestors, many others who live in the slums in large cities know no other possibility, chained to endemic poverty, the neglect of governments and the oblivion of society. A report by the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) shows that the meaning of sanitation for those who have absolutely no access to it is abstract and associated with the well-off classes who are difficult to reach on the social scale.

Much progress needs to be made in communicating the meaning of poor sanitation for human development. Paradoxically, little is known among the communities that suffer most from it, even though it is associated with the transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, polio and pneumonia. It is a social scourge in which women and children are the most affected. The WHO estimates that unsafe sanitation causes 280,000 deaths due to diarrhea every year and is a major underlying factor for several neglected tropical diseases, such as intestinal worms, schistosomiasis and trachoma, and is the basis for child malnutrition.

Building a latrine in Bangladesh. The success of any program depends significantly on the integration of appropriate facilities being carried out with adequate motivational activities. © Mirva Tuulia Moilanen / World Bank

Motivation, the first step towards sustainability

Despite progress in recent years, the health and economic crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened the already uncertain forecast of the attainment of the SDG 6.

In recent years the idea of sustainability of safely managed sanitation facilities has been significantly outlined and specified and has become an indispensable factor in any aid planning for those who lack it.

That same report from the University of Bangladesh pointed out that the beneficiaries of aid projects consider that the government and the NGOs should work together with them for the sustainable implementation of sanitation. They also feel that the success of any program depends significantly on the integration of appropriate facilities being carried out with adequate motivational activities. Without motivation, Bangladeshis find it very difficult to eradicate unsafe sanitation and open defecation from their country.

The CLTS method is proving particularly effective in a first phase of aid in which the goal is the empowerment of communities for the construction and maintenance of their own. © UNICEF

The CLTS method: motivation is the first step

The CLTS method (Community-Led Total Sanitation), driven by UNICEF, is a good example of an efficient motivational strategy to deal with open defecation that, whether due to culture or sheer poverty, is present in a community. The strategy of aid projects facilitators is to raise awareness by provoking a feeling of shame and then promote the belief that the community can achieve for itself the knowledge and the means to end a scourge that causes diseases, child mortality and limits its possibilities for economic and social growth.

In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the CLTS method is proving particularly effective in a first phase of aid in which the goal is the empowerment of communities for the construction and maintenance of their own latrines and education in hygiene to eradicate open defecation. These are key premises to guarantee the sustainability of facilities.

The project that the Foundation started with UNICEF in Burkina Faso, in one of the poorest areas of the country, is a good example. After the implementation of the CLTS methodology, a new project will now improve the sustainability of latrines. This will involve selecting 100 vulnerable households from 119 communities in the Léo commune, one of the most in need of sanitation, and improving existing latrines that will serve as a model for other families.

A manual for sustainability

In this second phase the We Are Water Foundation’s guidelines on sustainable latrine construction summarized in the Manual for the construction of latrines and wells will be followed. The Ministry of Water and Sanitation (MEA) and the Ministry of Health (MoH) of Burkina Faso will support these guidelines, as well as the regional technical services, communities and NGOs that collaborate with them.

The Manual for the construction of latrines and wells is the result of more than 10 years of work of the Foundation, in which it has carried out 54 projects that have benefited some 705,000 people in 24 countries. In 21 of these projects the Foundation has been fully involved in the problems of installing and using latrines in the neediest areas, especially in schools. This work has been carried out in the most depressed areas of sub-Saharan Africa, South America and India, in collaboration with organizations with extensive experience and solvency such as UNICEF, World Vision, Acción Contra el Hambre, Gramya Foundation, Habitat for Humanity, Educo, Intermón Oxfam, Mujeres por África and the Vicente Ferrer Foundation.

Culture and gender inequality, key factors

In sanitation, and in particular in latrine use, not everything works the same way in different cultures, economies and climates. Factors such as gender inequality, social prejudices and both material and educational resources need to be jointly considered with climate and the level of poverty when developing a sustainable sanitation aid plan. There are notable climatic differences between a school in Guinea-Bissau or a village in the Chaco-Chuquisaqueño in Bolivia; there are also significant cultural differences between schoolchildren in Zagora in the Moroccan High Atlas and those of Mymensingh, in Bangladesh or Andhra Pradesh in India. Each one of them needs to be considered when implementing a latrine.

Wherever it cannot be found, a latrine that provides safe sanitation is fundamental to the backbone of any development strategy. It is essential for health and for preventing diseases caused by fecal contamination. It is the key factor to eradicate open defecation and provide dignity and safety to women. Without clean and adapted latrines, adequate levels of schooling cannot be achieved. A latrine that meets the needs of the community, climate and culture is the first step towards growth.

Understanding these benefits allows the achievement of the spirit of partnership and community participation, without which people will never have real and effective ownership of their facilities. Helping to make this possible is the base of sustainability for any sanitation system.