This boreal summer of 2022 will add to the long list of alarming climatic abnormalities the droughts in areas of the planet geographically cataloged as “wetlands,” where their inhabitants do not remember a similar situation. It is not a personal perception; the observatory records are evident, and the media resonance corroborates it with shocking images worldwide.

The environmental and psychological impact of droughts is most significant in those areas where they are rare. © Alisdare Hickson – Greenwich, London

Alarm in green Europe

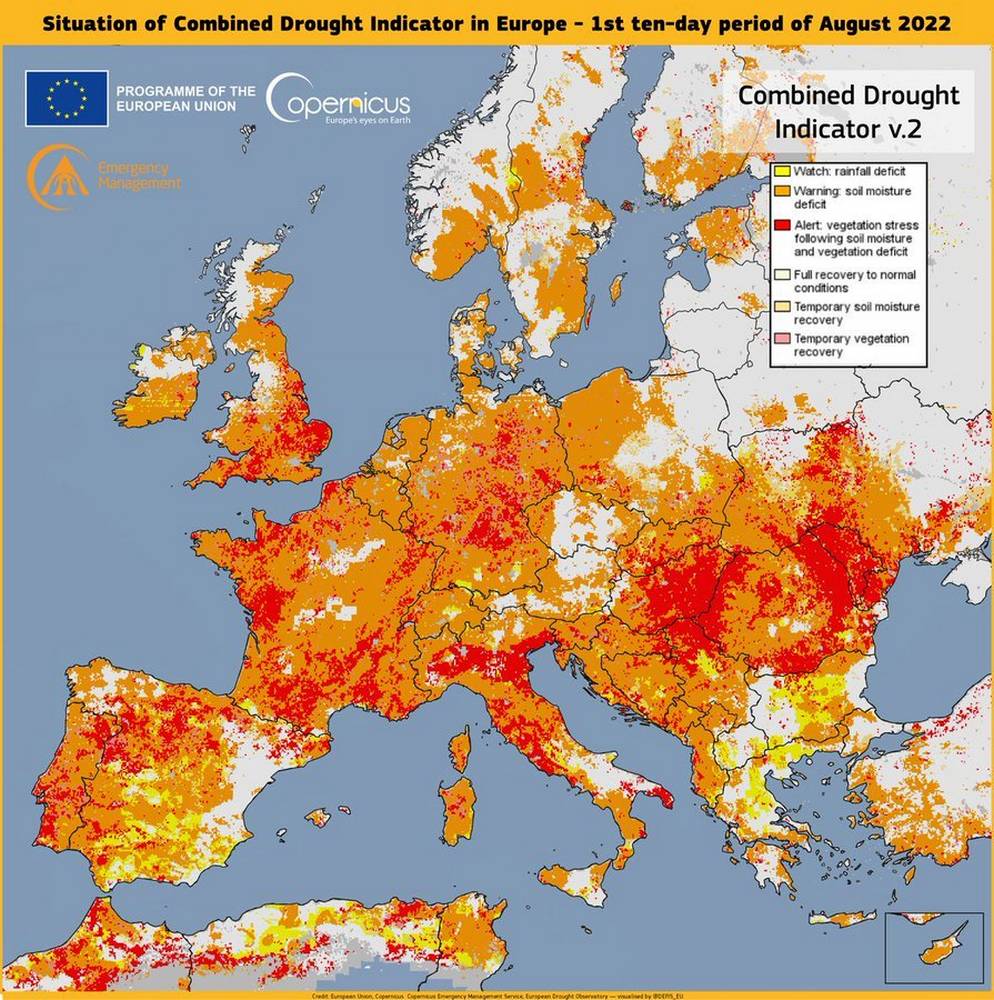

Drought has affected a large part of the European continent during July and August, after one of the winters and springs with the most significant lack of rainfall on record. According to the report Drought in Europe by the European Drought Observatory (EDO), 47% of the territory was in this situation during the last ten days of July, and 17% was at a high-risk level. The European Commission described the situation as “critical” and called on the governments of the affected countries to adopt “extraordinary measures” for water and energy management.

The report details how areas with usually cooler and wetter climates such as the Scandinavian Peninsula, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova, have received significantly less rainfall than average and how the moisture levels in their soils have dropped considerably. These areas stand out for their green landscapes, with flora, fauna, and a population very little accustomed to heat waves and droughts. Hence, their environmental and psychological impact is greater.

Drought scenarios in Europe are no longer exclusive to the southern Mediterranean. Map of the Combined Drought Situation Indicator for Europe for the first ten days of August 2022. You can navigate on the EDO interactive map. © Programme of the European Union – Copernicus

Droughts and heat have moved up the Earth’s latitude

The heat waves of this boreal summer have reached countries unaccustomed to these phenomena. In England, several places reached 40°C for the first time in their recorded history, as did many German observatories on the North Sea coast, such as Hamburg.

In France, records were broken with 42°C in Nantes and 42.6 in Biscarrosse, in the Landes department, where almost 7,000 hectares of pine forests were razed by a fire that forced the evacuation of 10,000 people on August 12. Throughout France, restrictions were imposed in 93 of the country’s 96 départements.

In the United Kingdom, July and August were the driest since 1976, and the Government declared for the first time in history a “red alert” for drought in eight of the 14 environmental zones into which England is divided. In some places, it had not rained for more than 140 days, the longest in living memory.

It is becoming clear what the IPCC predicted in its sixth report: heat waves in the northern hemisphere will rise in latitude and reach areas where they were unheard of. In the European citizen’s imagination, temperatures of more than 40º were exclusive to southern Spain and Italy, but this is no longer the case.

The heat waves of this boreal summer have reached countries unaccustomed to these phenomena. © Chris Walts

Rivers without water

Photographs of London’s yellowed parks made the front pages and opened the news. But the photos seen across the world were those of the upwelling of more than 20 hulls of German ships sunk in the Danube during World War II and forgotten ever since. Many still contain tons of ammunition and explosives and threaten maritime transport.

Similar situations have occurred in China’s rivers. In mid-August, the government issued its first national drought warning of the year after regions such as Shanghai and Sichuan experienced two months of extreme temperatures, a record length since records have been kept. Rainfall in the Yangtze River basin, the largest in the country and on the Asian mainland, was 40% lower than at the same time last year, a minimum since 1961. The declining flow of the Yangtze poses a threat to the food security and economy of a third of China’s population. This threat extends to the balance of the global economy.

In Europe, it is not only the Danube that has drastically reduced its flow. The water level of the Rhine, the great river artery of Western Europe (1,233 km, 883 of which are navigational), fell on August 12 to just 40 centimeters above the minimum depth necessary to allow navigation. The maximum load of the barges had to be limited from 6,000 tons to 800 tons, with the commercial impact of the increased price of transported goods.

In northern Italy, the Po, the country’s largest river, saw its flow drop by 80% in early August compared to the historical average, causing an unprecedented decline in agricultural, livestock and energy production.

In general, satellite data obtained by Copernicus program sensors showed, on August 23, an average negative anomaly of 30.5% in the flow of European rivers from June to August, reaching less than 68% at some points.

Apart from the damage to trade and food production, the water crisis has highlighted the importance of the water-energy relationship, unknown to a large part of the population. In addition to the drastic reduction of hydroelectric power, as has occurred in Switzerland, there has been a reduction in the production of some water-cooled nuclear power plants due to the reduced flow of rivers and the warming of their waters.

In northern Italy, the Po, the largest river in the country, saw how its flow decreased considerably at the end of June compared to previous years. This past August, its flow was 80% lower than the historical average.© European Space Agency

Losses in wetlands, famine in drylands

This summer, the lands of almost all of Europe, China, and much of the USA have gone thirsty. The people of the most economically powerful countries have been directly impacted by global warming. But the drought has also hit the poorest drylands with more severe humanitarian consequences. At the time of writing, the number of people affected by the lack of safe drinking water in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia had risen from 9.5 million to 16.2 million in five months. And UNICEF warns that child mortality in the Horn of Africa and the Sahel could be devastating unless urgent support is provided, as the risk of severe malnutrition and waterborne diseases converge.

This summer’s droughts offer sobering contrasts. While restrictions in wetlands leave some unable to water their gardens or wash their cars, lack of water causes famine, disease, and death in many poor drylands. All this should make the global society aware of the urgency of fighting global warming.