The city of Morelia has lost 70% of its surface water resources, while the remaining 30% has a level of pollution unfit for human consumption.

Urban masses that grow uncontrolled and without planning their water resources end up having water supply and sanitation problems. This has been the case in most major cities such as Mexico City, Mumbai, São Paulo, Cape Town and new African capitals like Lagos, Kinshasa, Nairobi, Yaoundé… to mention those with the largest slums.

Over the last decades, these problems have extended to many smaller cities that have also grown uncontrollably. Poor agricultural management and the lack of wastewater treatment have polluted the watercourses that surround and supply these cities. A good example is Morelia, capital of the Mexican state of Michoacán de Ocampo, a city with almost one million inhabitants, located in the Guayangareo valley, around 200 km west of Mexico City.

According to a study by the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH), the city of Morelia has lost 70% of its surface water resources since 1920, while the remaining 30% has a level of pollution unfit for human consumption. This deterioration was mainly unleashed after the 1960s with the massive urbanization of areas of high environmental value.

On the other hand, the Water, Sewage and Sanitation Operating Authority of the city of Morelia (OOAPAS) also recognizes a loss of 50% of water due to the poor condition of the supply network. This is an endemic problem in Mexico, which causes enormous water losses and subjects large cities to continuous water stress.

The deterioration of the Cointzio reservoir and the Mintzita wetland

The most serious situation is the pollution of the Cointzio reservoir, which supplies 60% of Morelia’s water. Sewage discharges together with high nitrogen and phosphorus levels from agricultural fertilizers have caused an accelerated eutrophication process. This has turned water into a breeding ground for aquatic plants like the Eichhornia crassipes, commonly known as water hyacinth, and different types of microalgae.

This vegetation layer affects the water temperature and oxygenation and ends up covering the entire surface, preventing the light from reaching the deepest areas and causing anoxia (lack of oxygen), as it hampers the photosynthesis of seagrass, which eventually dies. This is a very common phenomenon in other eutrophicated water bodies and very similar to the one that caused the environmental disaster of the Mar Menor, in Spain. Water hyacinths cause an additional problem: when they die they generate large masses of organic matter that fall to the bottom of the reservoir, reducing its depth and generating substances that are toxic to health.

Sewage discharges together with high nitrogen and phosphorus levels from agricultural fertilizers have caused an accelerated eutrophication process.

Morelia’s inhabitants face an additional problem: the La Mintzita wetland, its second water source after the Cointzio reservoir, is also degrading. The water body, which is estimated to supply around 300.000 city inhabitants, has lost 30% of its capacity in the last 20 years due to agricultural overexploitation and droughts. Industrial discharges have also contaminated water, which has lost most of its biodiversity. According to the Jardines de la Mintzita Environmental Community, the wetland could dry up entirely in seven years, and for this reason authorities have banned extraction in some parts of the basin.

Due to climate change, they (“piperos”) need to fetch water from further and further away, as the sources dry up or are polluted.

Water delivered on demand… for those who can afford it

In this precarious context, periods of drought cause acute shortage crises. In Morelia, the last one was unleashed in March, after two years of very little rainfall, during which agriculture absorbed 17% of the flow (500 liters of water per second) of urban supply, leaving 192 colonies of the municipality without water.

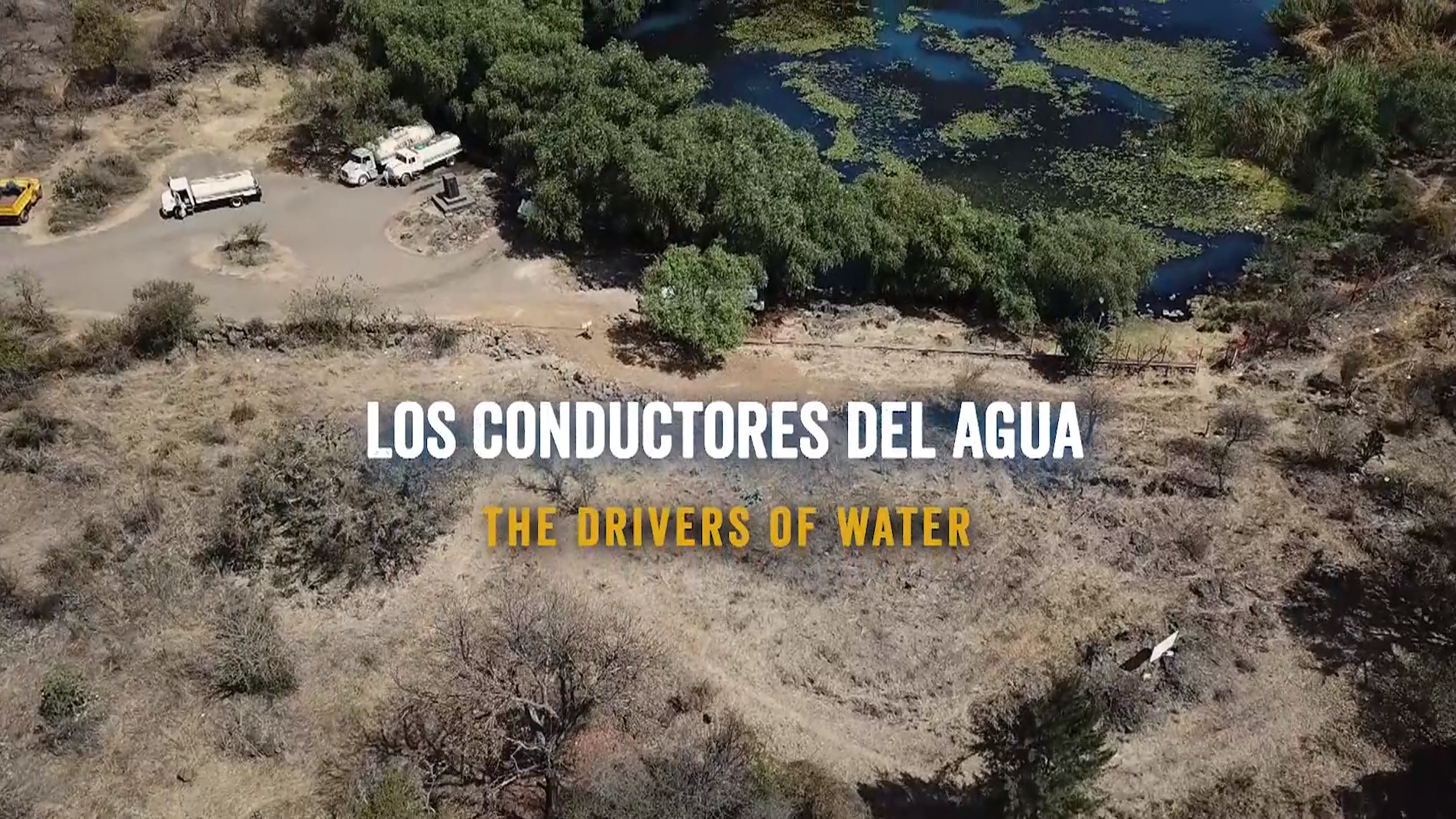

As a consequence, many families and many businesses in Morelia are obliged to buy water from “pipas”, tanker trucks that collect it from healthy springs and transport it to the city. At the La Mintzita spring alone, around 50 “piperos” collect water every day. Every truck can transport between 5,000 and 10,000 liters, so up to half a million liters can be extracted every day.

Prices per “pipa” are variable; they depend on the distance to be traveled, the price of fuel and the transported volume. They oscillate around USD30 (around 620 pesos) for 1,000 liters. As a result, the economically weaker population, such as the over 40,000 families that live in precarious huts in slums, cannot have access to water.

Water is further and further away

The short film Los Conductores del Agua – The Drivers of Water of Morelia, micro-documentary finalist at We Art Water Film Festival 5, bears witness to this situation. Fernando Rivera, a “pipero” for more than 30 years, has experienced day by day the deterioration of water and its transport problems. He explains that now, due to climate change, they need to fetch water from further and further away, as the sources dry up or are polluted. Water transport is their livelihood and the water they transport means life for those who receive it. Both depend on an uncertain evolution. Will there be water for Morelia?

Los Conductores del Agua – The Drivers of Water, micro documentary finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

The United Nations population growth forecast predicts that by 2035, 80% of the world’s population will live in cities, a proportion that already exists in many developing countries. If we continue at this rate, by 2050 urban population will have increased by 2.8 billion. Morelia’s problem, which is already occurring in hundreds of cities around the world, is becoming widespread. Will it be possible to supply that much water? Will it be possible to treat and sanitize it sufficiently and sustainably? The answer to these questions is key to attain the SDGs. The need for water balance in view of the demographic and climatic diversity is urgent.