In the summer of 2019, the images of 55 elephants who had died of thirst in the most important reserve of the country, the Hwange National Park, made the headlines worldwide. Sadly, they were more widely disseminated than the images of the human havoc due to the famine caused by drought in the country. However, they helped publicize the seriousness of one of the most severe climate and economic crises the world has suffered in the last five years.

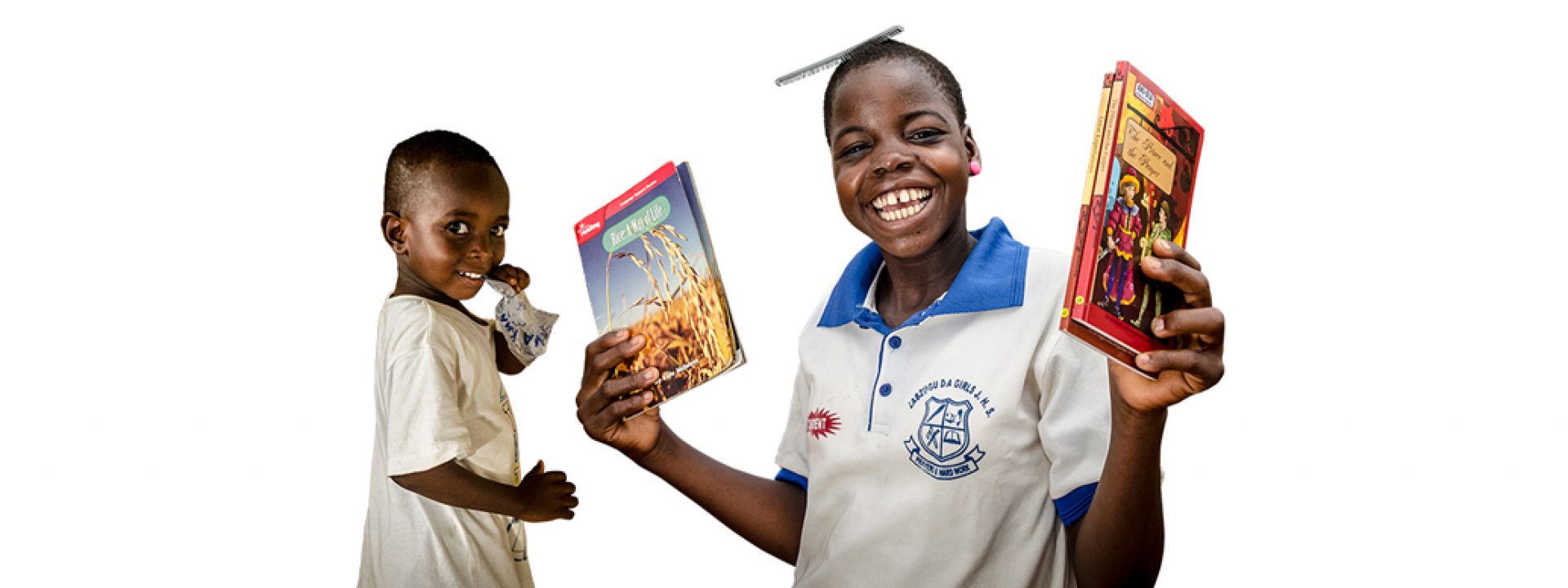

We are collaborating with World Vision in a project to bring water and create a vegetable garden for 1,000 schoolchildrenin the Lupane district, in the west of Zimbabwe. © World Vision

The climate crisis becomes an economic crisis

At the end of that same year, the UN, which had been warning of the situation months earlier, informed that Zimbabwe had lost 50% of its crops and 40% of its livestock. The three-year-long drought in large areas of southern Africa’s semi-arid and sub-humid belt was causing an unprecedented human drama and a migratory movement that the authorities could not control. In March, the country was severely hit by Cyclone Idai and suffered floods that caused more than 400 deaths and left 217 people missing along the border with Mozambique (see disaster relief project).

The World Food Programme (WFP) requested urgent assistance from the international community to meet the needs of more than four million people, almost half of the country, whose nutrition levels were below the minimum requirements established by the WHO. The WFP estimated the amount of aid at more than US$200 million to meet the needs in the first half of 2020.

According to the JMP, in 2020, access to safe water sources was only guaranteed for 30% of the population. © World Vision

It rained in 2020, but not enough to mitigate the damage caused. The economic crisis, endemic in the country during the last decade, coincided and worsened with the climate crisis. The Covid-19 pandemic shifted international media attention away from the disaster: galloping inflation, foreign currency shortages, and rising prices of basic food due to poor crops, with the risk of extending famine to the majority of the country’s population.

The third most vulnerable country to drought

The lack of water was affecting an extremely vulnerable area. The WHO and the WFP recalled in their statements a study carried out in 2019 on the agricultural vulnerability of countries to drought, which placed Zimbabwe in third place, after Botswana and Namibia, countries on the same climate zone characterized by the transition between semi-aridness, aridness, and dryness of the sub-humid regions of southern Africa. The recurrent droughts of the last few years have dramatically hampered the country’s efforts to leave poverty behind by significantly compromising the advances towards SDG 6, essential to attain it.

The recurrent droughts of the last few years have dramatically hampered the country’s efforts to leave poverty. © Aurélie Marrier d’Unienville / IFRC.

Zimbabwe’s water access and sanitation data reflect this vulnerability. According to the JMP, in 2020, access to safe water sources was only guaranteed for 30% of the population, while almost 7%, one million people, continued to use surface water to meet their needs. There are no recent data, but reports by NGOs and journalists who have traveled the country during the pandemic state that due to supply cuts, many families have returned to old wells and reservoirs to fetch water, increasing one of the most unsafe practices for people’s health.

Today, in many wells which have not dried up, the unhealthiness of water has increased due to excessive extraction without hygienic measures and the receding water table. In many communities in the west of the country, up to 10,000 people are supplied by one single well, while in other regions, the population must walk more than 10 kilometers to have access to safe sources.

Bulawayo, the second-largest city in Zimbabwe, is an example of the seriousness of the lack of supply. Its town council is considering recycling water from a reservoir polluted with sewage due to the impossibility of providing a continuous supply to its 650,000 residents.

The access to sanitation and hygiene services has also been affected by the crisis. In rural areas in Zimbabwe, 23% of the population, around 3.5 million, practice open defecation, which is likely to increase in the 2021 statistics.

Water for schools

Even before the crisis, the situation in the country’s schools was precarious, and the drought has made it worse. In 2020, according to the JMP, some 360,000 schoolchildren in Zimbabwe had no access to drinking water in their homes, and nearly 1.6 million had limited access (when walking time to the source of drinking water is more than 30 minutes). More than 155,000 did not have any sanitation facilities, and around 1.67 million had no handwashing facilities at all.

The project is based on drilling a solar-powered pumped well and installing a water distribution system for drinking and hygiene purposes. © World Vision

In the Lupane district, in the west of the country, we are collaborating with World Vision in a project to bring water to the Ngubo school and community. Of the more than 109,000 inhabitants of Lupane, 74% live in extreme poverty, and their situation is a clear example of the vulnerability of those who live dependent on climate conditions. Endemic in the last decade, food insecurity has increased due to drought, and the population struggles to maintain their precarious water sources and manage their crops.

The project is based on drilling a solar-powered pumped well and installing a water distribution system for drinking and hygiene purposes. We will also create a school vegetable garden to provide students with a nutritional supplement and train them in agricultural practices as part of their school curriculum. This vegetable garden will also provide the school with a source of income thanks to the sale of surplus produce.

The most valuable contribution of the aid projects is the creation of Water Committees, which guarantee the sustainability of the facilities and the enrichment of the community’s water culture. In the case of schools, this aspect takes on particular importance, as it turns schoolchildren into agents for transmitting knowledge to the rest of the community. In the Ngubo school, students will also participate in the maintenance and repair of facilities so that when they finish their classes, they can apply this knowledge in their homes and benefit the community.

Schoolchildren, the basis for achieving the SDGs

In the 11 years we have been developing projects, we have provided access to water, sanitation, and hygiene to more than 86,000 children and their teachers, indirectly benefitting around 56,000 members of their families and communities. In this article, you will find a summary of all of them, carried out in 11 countries.

In all of them, we have seen that achieving SDG6 —and indeed all SDGs— adapting to climate change and mitigating its effects will not be possible without access to education for those who are now schoolchildren.

In the most disadvantaged communities already affected by the climate crisis, children must act as active agents to create social knowledge that makes them resilient. Knowing about climate, agriculture, water and sanitation facilities management will make them resistant and resilient. They are the hope of a wounded planet.