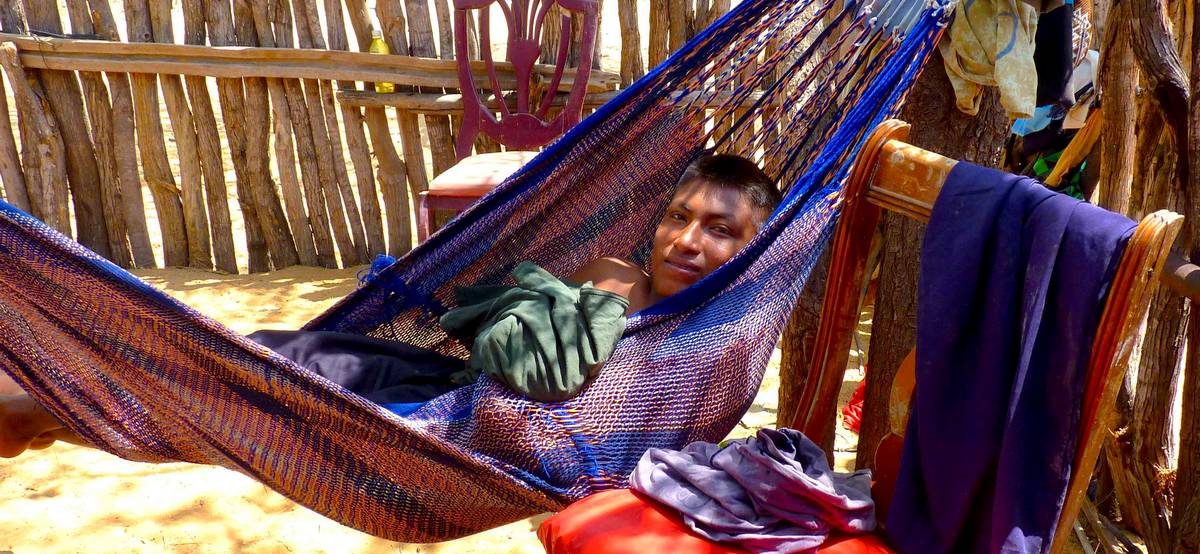

In the La Guajira peninsula, mining, global warming, and neglect threaten the “children of the rain god and Mother Earth.” In the image a Wuayuu family from the Guajira desert in Colombia. © Petruss

The Wayuu people, also known as Guajiros, feel they are children of Juyá, the god of rain, and Mma, Mother Earth. That feeling is deeply rooted since they arrived in the La Guajira peninsula more than 20 centuries ago. There, the Wayuu people have survived in harmony with an environment of great water contrasts, which environmental scientists often call “the world’s climatic summary.”

Located south of the Caribbean Sea, this land shares its territory between Colombia and Venezuela and is marked by the peninsula’s central semi-desert, the only Caribbean dryland. This has been the primary natural habitat of the Wayuu people, and a culture marked by an intense relationship with water and land has been forged there.

Children of the rain, the micro-animation short film byAnn López Angulo, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5, describes with images full of symbolism the essence of the Wayuu’s water culture and how their relationship with it is being cut short by the environmental deterioration caused by mining and out-of-control industrialization.

Children of the rain, by Ann López Angulo, finalist in the micro-animation category at the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

All climates, all kinds of water

The trade winds have turned La Guajira into an exceptional climatic classroom. On reaching it, the northeasterly winds collide with two mountain ranges, the Macuira and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. In the extreme northeast, the Macuira mountain range traps the humidity of the winds that create a unique ecosystem windward with areas of dense fog and forests. Downwind, the trade winds, dried out and reheated by the foehn effect, generate a sizable semi-arid zone where rainfall barely exceeds 300 mm per year.

Downwind, in La Guajira, the trade winds, dried out and reheated by the foehn effect, generate a sizable semi-arid zone where rainfall barely exceeds 300 mm per year. © Luis Alveart_Kashurop Cabo de La Vela – La Guajira.

Likewise, the spectacular Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta rises in the extreme southwest of the peninsula. It is the highest coastal mountain range in the world and the highest in the tropical zone, with peaks over 5,000 meters high. The trade winds end their journey through the Caribbean by colliding with the imposing mountains, causing abundant rainfall that usually exceeds 3,000 mm each year. Beyond 4,000 meters, they cover the crests of the Sierra with perpetual snow, creating a landscape of extraordinary beauty. Thus, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta has one of the broadest temperature ranges on the planet: the average temperature ranges from 30°C on the Caribbean beaches to 0°C on the highest peaks of the Sierra. UNESCO declared it a Biosphere Reserve in 1979, given the network of ecosystems that harbor countless forms of life.

Moreover, the streams of the peninsula, at their mouth in the Caribbean Sea, form lagoons and a long line of marshes along the peninsula’s western coast, which are flanked by mangroves of high ecological value. For centuries, the diverse species of fish, crustaceans and mollusks in this habitat have provided sustenance for the Wayuu people, as well as being home to numerous bird species.

The spectacular Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta rises in the extreme southwest of the peninsula. It is the highest coastal mountain range in the world and the highest in the tropical zone, with peaks over 5,000 meters. © Lobocordero5

A threatened culture

Snow, rain, hurricanes, rivers, fog, arid lands, wetlands… The Wayuu communities have learned to live and understand the vital relationship with water in all its states, including the destructive power of tropical cyclones. They have learned to predict rainfall, accurately coordinate planting and harvesting with the seasons, fish and gather crustaceans in the mangroves, transport water from wells and springs, and water their livestock with just the right amount.

But for decades, this relationship has been in jeopardy. Pollution, alteration of water courses, and climate change are leaving the Wayuu people without access to water. The most disastrous case is that of the Ranchería River, the most important river in the region, which has been altered by the mining industry and irrigation dams. Its source is in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and it flows 150 km to its mouth in the Caribbean Sea, feeding a large part of the aquifers in its basin.

The El Cerrejón coal mine, located in the Ranchería river basin, is one of the largest open-pit mines in the world. The mine has been a significant source of contamination of the water sources that supply the Wayuu people.

The situation worsened in 2010 with the construction of the El Cercado dam to provide water for mining and monoculture rice and palm plantations. The dam altered the river’s course to the delta at its mouth, altering the aquifers downstream and damaging the ecological balance. Contrary to legal requirements, the construction of the reservoir was not communicated or consulted with the Wayuu community, which saw surface and groundwater flows decrease, drying up many of its sources and intensifying the effects of the droughts that hit the region between 2011 and 2015.

UNICEF repeatedly denounced the abandonment of the Wayuu people and the high rate of malnutrition caused after the reservoir was put into operation. In 2015, the La Guajira region reported a figure of 46 deaths per 1,000 children under one year of age due to malnutrition; among children under the age of six, this figure increased to 60 deaths per 1,000.

Like most ethnic groups in Latin America, the Wayuu people are threatened. © Gustavo La Rotta Amaya

Fight against neglect

The Wayuu people have dual nationality and freedom of movement between Colombia and Venezuela. Still, political conflicts, insecurity, and economic crises have relegated their problems to the back burner in the governments of both countries. Like most ethnic groups in Latin America, the Wayuu people are under threat.

A look at the past can give us pause for thought. Ancestral water cultures are examples of resistance and resilience in the face of climatic problems. Many success stories, such as the Inca hydraulics that are currently inspiring agricultural development in the Andean region of Peru, show the regenerative potential of this almost forgotten knowledge.

At the Foundation, one of our lines of work goes in this direction: helping to recover ancestral cultures, such as that of the Indian Baori – whose essence is the basis of many of the Foundation’s projects in Andra Pradesh -, the water use of the Aymara and Uru culture on Lake Titicaca, and the agricultural techniques of the Mayangna in Bosawas. They are a source of fundamental knowledge for the transformations needed to achieve all the SDGs, especially SDG 6, which refers to access to water.

We are all children of the union between water and land. Awareness of this should lead us to preserve and extend ancestral heritages, especially those of indigenous peoples on the verge of disappearing.