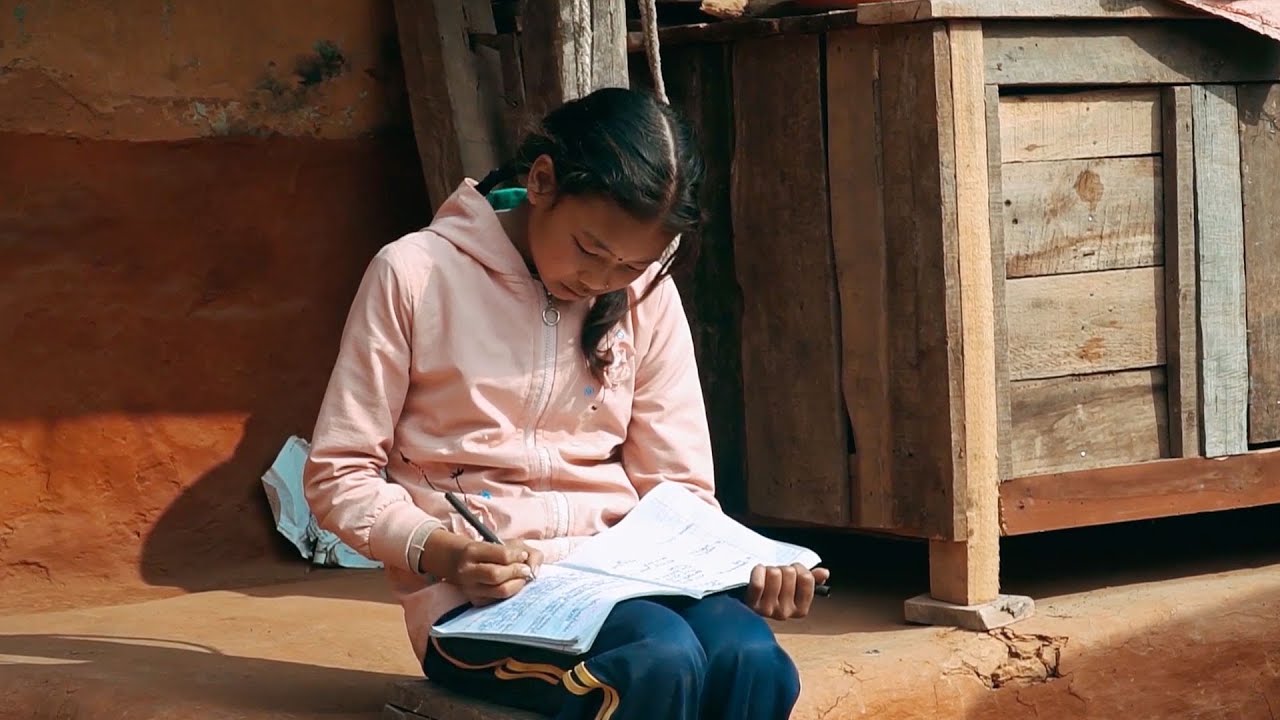

Sumnima is unable to complete her homework. Her mother sends her to fetch water every day from a precarious source that supplies the village where she lives in the Karnali province. Like 24 million other Nepalis, 82% of the population, Sumnima has no water supply at home and must walk a long distance to fetch water.

The short film Homework, a finalist in the fifth edition of the We Art Water Film Festival, shows the consequences Sumnima suffers: she cannot finish her homework. Millions of teenagers like her find themselves in this situation around the world day after day.

The short film Homework, a finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5, shows how Sumnima, a village school student, cannot complete her homework because she has to fetch water for her family.a

Every year, 45 billion hours are spent fetching water. That’s an average of 125 million hours a day, spent mainly by women and girls in the world’s poorest regions. These are hours lost to work, school, home, and community. Our #NoWalking4Water campaign has more details on this scourge to help spread a message to end this wasted time for personal development, health, and future prospects.

Sumnima is unable to complete her homework. Her mother sends her to fetch water every day from a precarious source that supplies the village where she lives in the Karnali province.

After the earthquake, Nepal is having trouble getting off the ground

Nepal has the second largest water resources in the world. According to the World Bank, it has 2.7% of the Earth’s available freshwater, making it second only to Brazil in terms of water reserves. However, according to the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP), only 5.1 million inhabitants, 17.5% of the population, had safe access to water in 2020.

Rural areas bear the brunt. In 2020, almost 20 million rural Nepalis (74.46% of the population) had to leave their homes to fetch water. Nearly one million accessed unsafe sources, and more than 300,000 were forced to draw from surface water. Overall, only 15 % of the rural Nepalese population had access to a safely managed source.

The last earthquake on 25 April 2015 reached a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. Its impact was severe, and entire mountain villages were destroyed. Laxmi Prasad Ngakhusi / UNDP Nepal

According to the JMP, Nepal is one of the few countries where this proportion has worsened since 2015 when 6.8 million (25%) had safe access to water. The causes of this degradation can be found in aging infrastructure and earthquakes that have damaged sources, supply, and sanitation facilities.

The last earthquake on 25 April 2015 reached a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. Its impact was severe, and entire mountain villages were destroyed. The official death toll was 7,000, and more than 9.5 million people were left in need of humanitarian assistance, half of them children. Lack of food and water caused 2.8 million internally displaced people, and Kathmandu, the country’s capital, received thousands of migrants fleeing from ruin.

The water supply is highly vulnerable to natural disasters. Whether due to an earthquake or a flood, the first consequence in an area with precarious access to water is the contamination of wells and aquifers. In earthquakes, supply systems deteriorate, which is aggravated in developing countries with no investment in infrastructure, and those affected are left without access to water, sometimes, as in the case of Nepal, for years.

Even today, the country has not yet recovered from the catastrophe. The Foundation has collaborated in two aid projects. In the first project, with World Vision, we supplied jerry cans that helped some 1,500 families transport and store water to survive. In the second project, with Intermón Oxfam, we sent more than five tons of water and sanitation materials. This provided clean drinking water to more than 30,000 people.

Nepal’s water abundance is also under threat as global warming significantly damages the mountain ice reserves. © Ankur Panchbudhe

The threat of shrinking ice

Nepal’s water abundance is also under threat as global warming significantly damages the mountain ice reserves. Melt from the Himalayas’ nearly 3,000 glaciers and lakes feeds the more than 6,000 rivers and streams that flow through its valleys. This enormous flow, which supplies more than a billion people downstream in India and Pakistan, is dwindling. Recent studies warn that the ice of the Earth’s highest mountain range will have shrunk by 70-99% by 2100.

Nepal is struggling to reverse the paradox of abundant water resources and precarious supply. It has undertaken ambitious infrastructure projects in recent years and revamped its water and sanitation management systems. This allows it to face the future with less uncertainty.