The rapid data collection to characterize a problem is the first step toward solving it. In water and sanitation, “real-time” data has become essential, from flood and pollution alerts to ensuring the water security of entire communities.

Traditionally, these data have been gathered through a network of sensors installed in water treatment and purification systems to monitor pollution, as well as in river channels where flow sensors provide warnings about rising waters. These technologies are characteristic of advanced economies that have developed the concept of “smart water”: intelligent networks, many of which are already managed by artificial intelligence.

Currently, these systems monitor the water supply and sanitation networks of major cities in the developed world and are crucial for ensuring the quality of water services. However, they fail to address the vast global extent of freshwater, which is most at risk due to climate change and increasing pollution.

Water mapping projects range from simple on-the-ground observations to advanced satellite detection powered by artificial intelligence. © Freepick

A Global Vision: One Water for the Whole Planet

In recent years, new initiatives have emerged to complement these traditional systems, covering freshwater and marine ecosystems. These projects not only generate essential scientific and technological knowledge but also aim to make it accessible to citizens, encouraging their active involvement in water mapping efforts.

These initiatives can be grouped into two categories: those based on data collected through people’s observations and those using the most advanced satellite technologies. Both approaches complement each other and offer key water monitoring and sustainable management benefits.

1 – Local Observations

These initiatives are revolutionizing public awareness of water access issues because they generate data without intermediaries. The information is presented on user-friendly and educational online platforms that ensure high reliability while encouraging active participation.

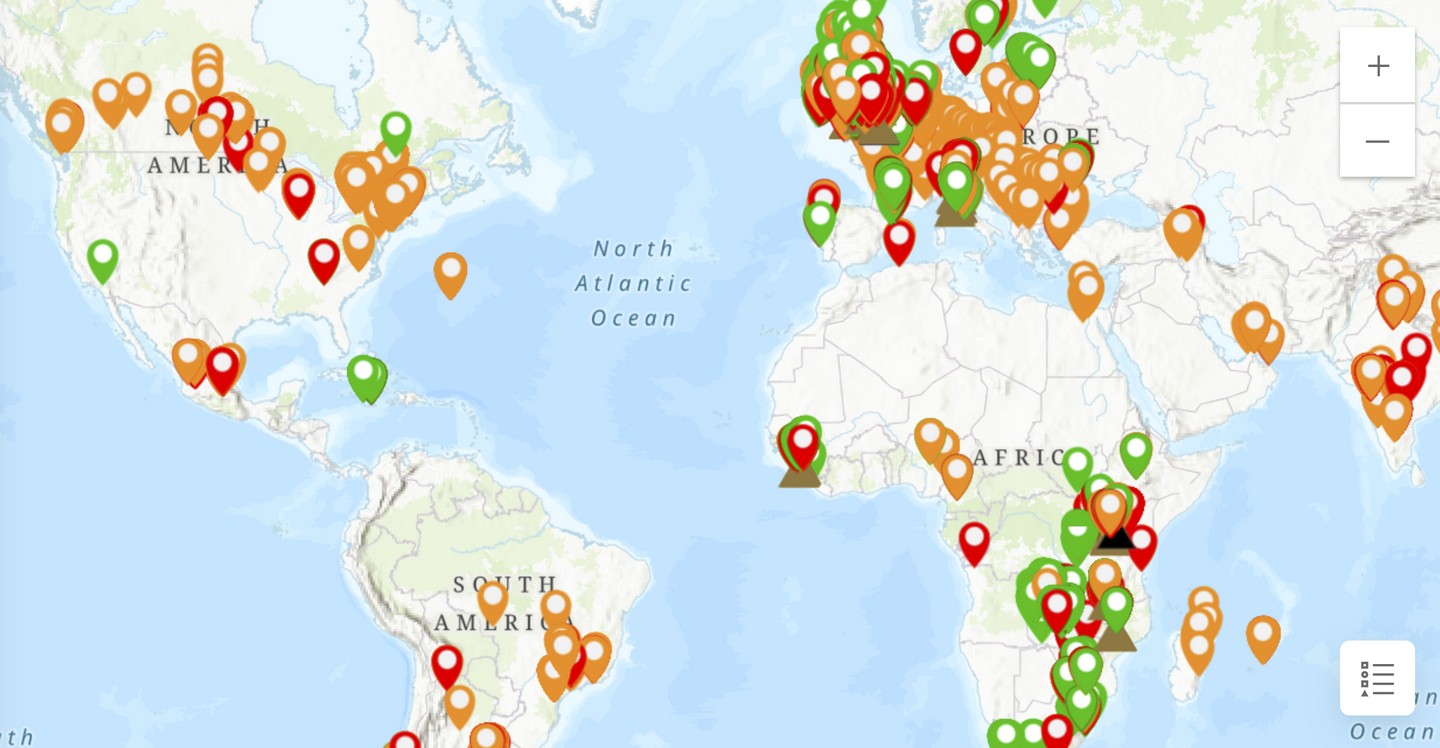

A project that highlights the vital role of people in water observation is FreshWater Watch, an initiative launched in 2012 by Earthwatch Institute, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to participatory science and environmental conservation. Through this program, volunteers worldwide collect key water data from local sources, such as turbidity and nutrient levels. This data is integrated into a global platform and is the basis for scientific research and public policy development.

FreshWater Watch has expanded globally and is now available in 10 languages. Its impact is particularly significant in regions facing severe challenges in accessing potable water. The platform not only collects data but also empowers participants by offering online training materials that ensure accuracy in data collection. Additionally, it provides educational resources on the water cycle, fostering deeper knowledge and more informed participation.

Details of the information mapped by communities in FreshWater Watch.

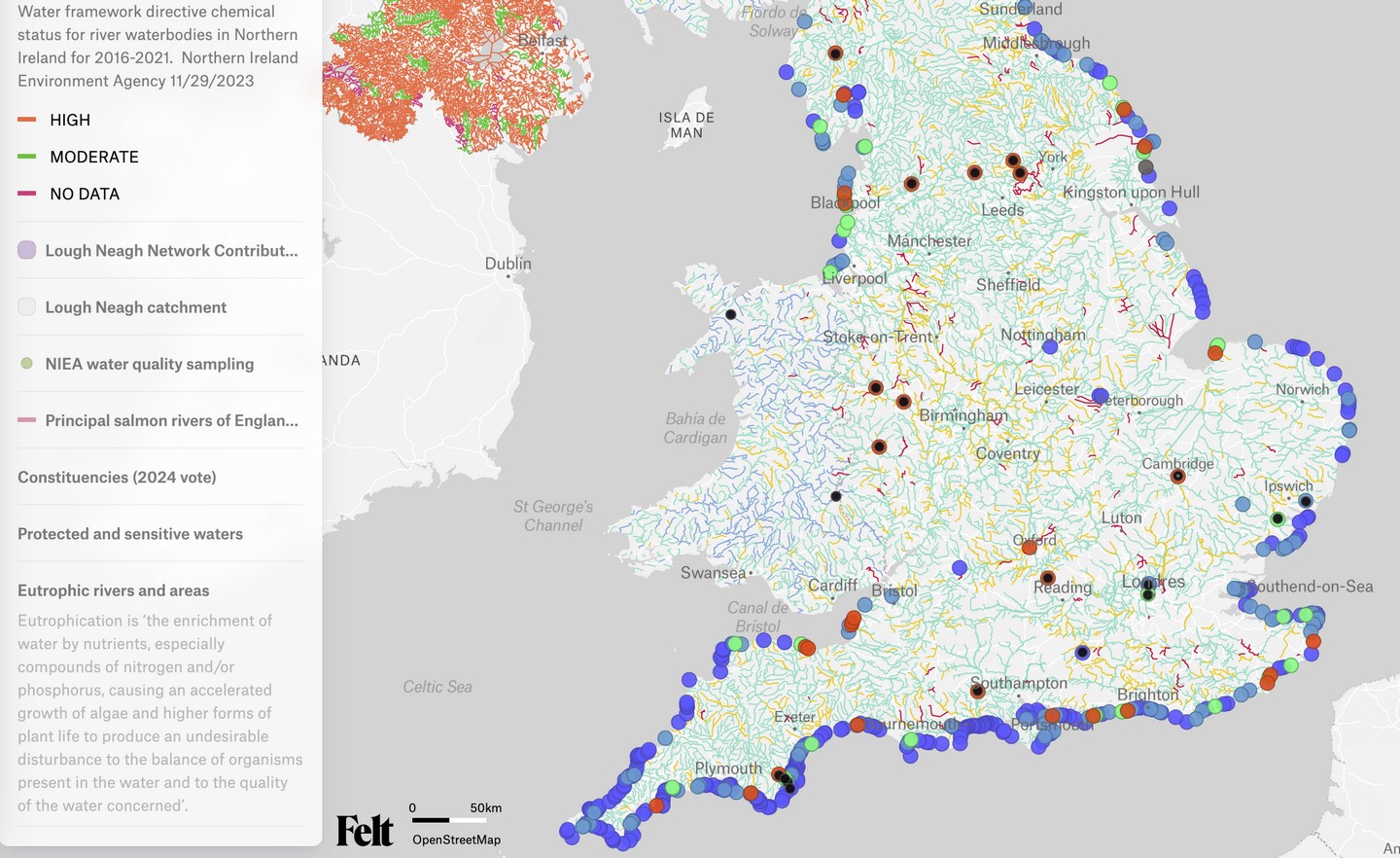

Another initiative that directly connects citizens with water quality data is the Watershed Pollution Map, developed in the United Kingdom by Watershed Investigations, an independent research group led by environmental journalists. This project emerged in response to the limited media coverage of water issues, aiming to inform and communicate with scientific accuracy.

The data featured in the Watershed Pollution Map comes from multiple sources, including government agencies, academic research, and public records. It is regularly updated to reflect changes in the environment and environmental policies. The platform compiles over 120 datasets that detail pollution sources affecting rivers, lakes, groundwater, coasts, and other aquatic ecosystems.

The Watershed Pollution Map stands out for its interactive platform, enabling users to identify specific problems in different areas and visualize regions impacted by various pollutants. This approach combines accessibility with accuracy, fostering a deeper understanding and greater awareness of water quality challenges

Details of the Watershed Pollution Map. All watersheds are marked, along with incidents in coastal areas.

2 – Satellite Data: High Technology Within Everyone’s Reach

In 2009, the GRACE satellites (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) achieved a breakthrough by detecting variations in Earth’s gravity caused by fluctuations in water masses. They successfully mapped changes in groundwater storage over time. This was the first time satellite technology was able to monitor groundwater, providing invaluable data and opening new avenues for water management, famine prediction, and climate change adaptation.

One alarming conclusion caught the attention of Indian hydrologists and FAO analysts: aquifers in the upper Ganges Basin were depleting at a rate of 33 cm per year in their water table. The study further revealed that 108 cubic kilometres of groundwater had vanished from aquifers in the region between 2002 and 2008. This is an enormous amount, equivalent to three times the volume of water stored in Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam, the largest water reservoir in the United States.

In recent years, several satellite projects have focused on making water-related data more accessible to both scientists and the general public. These initiatives aim not only to advance scientific understanding but also to democratize access to data, fostering a greater awareness of global water challenges and their link to climate change.

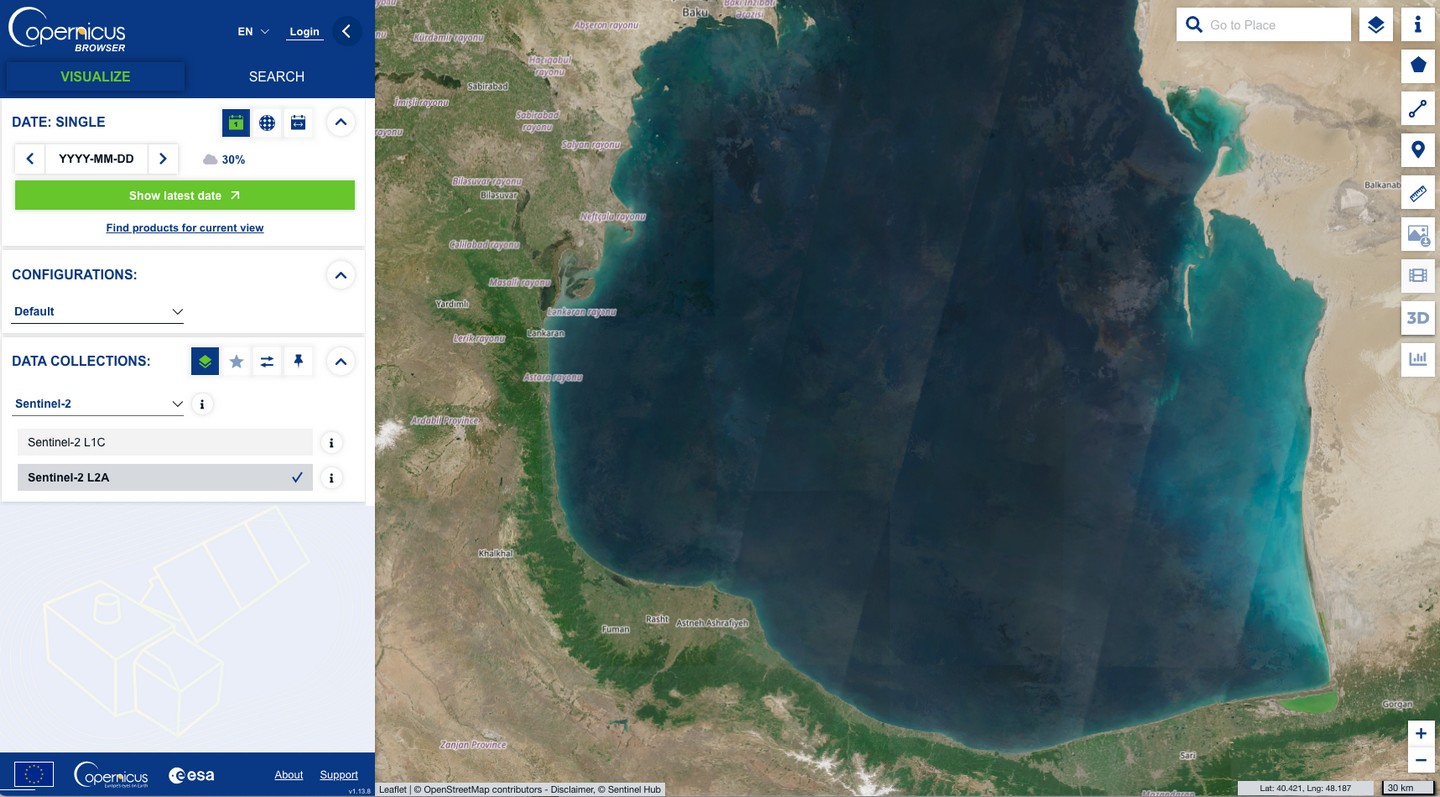

One standout project is Copernicus Sentinel-2, a European Union Earth observation program that provides high-resolution images of water bodies and their surroundings. This system excels at measuring parameters such as turbidity, algae growth, and surface water chemical characteristics. Furthermore, its data is presented through an interactive platform, significantly enhancing accessibility and enabling both scientists and citizens to explore and better understand the information collected.

Interactive map details from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem.

Satellite programs are providing invaluable historical coverage for climate and water cycle studies. For instance, the Global Surface Water Explorer acts as a virtual time machine, mapping the location and temporal distribution of water surfaces globally over the past 3.8 decades. It also provides detailed statistics on their extent and changes over time.

Additionally, the MODIS satellites (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) are essential tools for analyzing long-term trends in parameters such as water surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration, and watercolour. These datasets are fundamental for understanding how environmental and climatic changes affect aquatic ecosystems worldwide.

These platforms, powered by cutting-edge AI systems, are bridging the information gap on water quality. They play a critical role in policymaking and foster the engagement of diverse stakeholders, ranging from scientists to citizens.

Their impact extends beyond data collection. By democratizing access to crucial information, they empower communities and promote more transparent and informed water management. These tools have become indispensable allies in addressing global water challenges, integrating science, technology, and civic participation into a united effort.