India is experiencing the worst wave of infections and deaths the world has seen since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Bathalapalli Hospital, one of the healthcare centers of the Vicente Ferrer Foundation. © Rodríguez Roberto

The second wave of the pandemic, which started at the end of March, has exceeded all forecasts in India. It began last month with an alarming exponential growth: in the week from the 18th to the 25th April, 2.24 million cases and 16,257 deaths were registered; on the 1st May, new cases reached more than 401,000 and 3,523 deaths were reported all around the country in 24 hours. On that day, the official number provided by the government reached 211,853 deaths since the outbreak of the pandemic, but health professionals fighting for life or death against the disease and WHO observers claim that these numbers are not reliable and many point out that they may be up to 30 times higher, since a high percentage of the most neglected population is suffering the disease in their homes with no treatment or medicines.

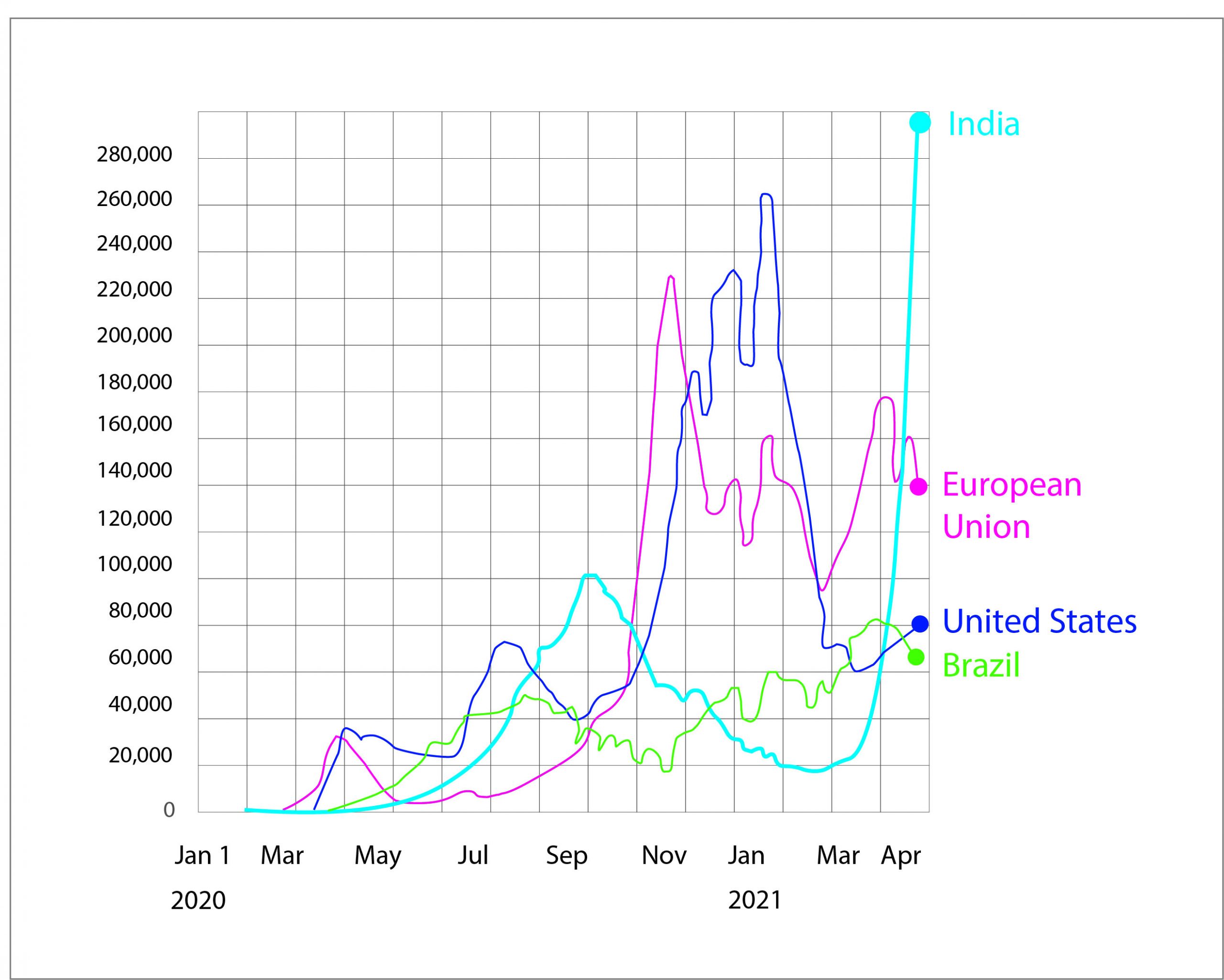

New confirmed cases of Covid-19 in United States, Brazil, European Union and India. Data updated April 23 2021. Source: Financial Times analysis data from Johns Hopkins CSSE, the WHO, the UK Government coronavirus dashboard, Public Health France and the Swedish Public Health Agency.

The second wave, out of control

Hospitals are overcrowded and lack basic supplies such as oxygen, mechanical ventilators and virus test kits, and healthcare workers are being decimated by the pandemic. On the 21st April, the demand of oxygen in India reached 13.04 million cubic meters, six times more than the second neediest, Turkey, whose shortfall on that day reached 2.77 million.

A case in point is Bathalapalli Hospital, one of the healthcare centers of the Vicente Ferrer Foundation, which a year ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, was declared by the Andhra Pradesh State Administration as a referral center for Covid-19 patients. Today, the hospital is completely overwhelmed. The Vicente Ferrer Foundation launched the campaign “Oxygen for India” on the 26th April, with the aim of obtaining a generator of this gas, an essential element for the treatment of seriously ill patients, whose demand has jumped throughout the entire country.

Hospitals are overcrowded and lack basic supplies such as oxygen. Bathalapalli Hospital, one of the healthcare centers of the Vicente Ferrer Foundation. © VALLDAURAAINA.

The situation in the poorest regions of India, where the We Are Water Foundation is currently collaborating in different aid projects with organizations such as the Vicente Ferrer Foundation, World Vision, Habitat for Humanity and Gramya Foundation, is particularly dramatic because of the abandonment of its inhabitants, the lack of healthcare resources and other endemic diseases that plague areas lacking access to water and basic sanitation. There, Covid-19 is now affecting a population that loses more than 10,000 children every year due to endemics produced by the poor condition of water. What possibilities are there for effective action against coronavirus?

Migratory instability

The healthcare chaos overlaps poor medical coverage and the endemic problems of lack of access to water and sanitation in the marginal slums. © Emmanuel DYAN

During the first wave of the pandemic, the Indian government established a severe lockdown. It did so suddenly, with less than four hours’ notice, putting tens of millions out of work in the poorest neighborhoods of the city. The lockdown was implemented when many were returning to their home villages, so that thousands of people had to continue their journey on foot or with improvised or clandestine means of transport and a very large number of them died.

Now, in this second wave, the government has not announced a national lockdown; but, fearing to be trapped again, millions of workers started a massive and hasty return to rural areas in April. This exodus has caused a chaotic situation that has only encouraged the spread of contagion.

The worst healthcare system for a pandemic

© REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

In 2019 India invested approximately 1.25% of its GDP in (public and private) healthcare, while in 2018 it reached 0.9% (Statista). These are data that place the second most populated country in the world among those that invest the least: in 2018 the USA reached 14.3% of the GDP in healthcare, Spain 6.2% and Mexico 2.8%, for instance. Many analysts and those critical of the government consider that these numbers are inflated and that the real investment rate is close to 0.4%. A figure that explains the severe situation experienced by the country, especially considering that approximately three quarters of the healthcare system are in the hands of the private sector.

In 2018, the government launched its National Health Protection Scheme (PMJAY, in Hindi) with the aim of providing medical coverage to 500 million Indians, among them the most vulnerable. The plan was commonly called Modicare, in reference to the Prime Minister’s name (Narendra Modi), who announced it as the world’s largest public healthcare program. But even before the pandemic, Modicare, which was based on a 15% increase of the investment in the healthcare system, had proven to be incapable of palliating the deficit of public services and showed cracks in its effectiveness, partly due to the fraudulent use of the provided financial aid and partly due to the lack of an efficient healthcare system to implement it. Covid-19 has managed to dismantle the objectives of PMJAY.

Lack of hospital transparency

The reality of the inadequacy of public hospitals to face the pandemic is reflected in Chengalpattu, in the state of Tamil Nadu, where the Foundation has finalized a project with World Vision with the aim of facilitating the management of wastewater of the Government Chengalpattu Medical College & Hospital, which is one of the two that treated Covid-19 during the first wave of the pandemic.

This university hospital, one of four public hospitals in the district (there are 57 private ones), has 1,300 beds and provides free medical care mainly to low income communities. The facility has been powerless to treat the 86,265 cases in Chengalpattu since the outbreak of the second wave. According to The Indian Express, only on Tuesday, May 4th, the hospital detected 1,608 new infections, and during that night at least 13 patients died in the hospital in just four hours, triggering a bitter controversy that shows the lack of government transparency regarding the evolution of the pandemic: while family members and some health personnel blame the lack the oxygen for the accumulation of deaths, the hospital management and the authorities deny this cause.

The reality of the inadequacy of public hospitals to face the pandemic is reflected in Chengalpattu, in the state of Tamil Nadu, where the Foundation has finalized a project with World Vision. © World Vision

In the week from the 18th to the 25th April, 2.24 million cases and 16,257 deaths were registered; on the 1st May, new cases reached more than 401,000 and 3,523 deaths were reported all around the country in 24 hours. © REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

Triumphalism, relaxation and a virus that kills

What has happened to bring about this situation? The causes of the brutal increase of infections are still not clear, but epidemiologists point to a combination of two factors: the relaxation of prevention measures and the appearance of a new and particularly virulent strain of the virus.

The worst was feared during the first wave, but disaster did not strike. Many speculations were made as to why, from climatic to genetic causes, without reaching scientific conclusions and the government adopted a triumphalist stance, attributing the success to the prevention measures and the country’s healthcare system. The subsequent relaxation led to allowing massive religious celebrations and political rallies with hardly any prevention measures, which undoubtedly favored contagion.

On the other hand, in December 2020 it was detected that new variants of the virus had spread in India. One of them, the B.1.617, is a transformation of SARS-CoV-2 (the biomedical name for coronavirus). This variant presents two mutations – L452R and E484Q – that give the microorganism a certain resistance to human immune defenses, thus increasing its contagiousness.

However, to date it is not known with certainty if that variant has caused the exponential increase of contagion, although it is evident that the prevalence of that version of the virus has grown exponentially in the last few months and continues to do so. To know for sure, we will have to wait until there is the capacity in the country to genetically sequence between 5-10% of all Covid-19 test samples, which does not seem possible in the short term. By way of comparison, one of the countries that performs the most genetic sequences, the United Kingdom, manages to analyze 10% of the cases.

Vaccines and water

Another severe problem is the lack of vaccines. Since the Indian government launched the “greatest vaccination campaign in the world” in January, only 155 million doses had been injected by May 3rd, reaching 11.5% of the population, although the full vaccination scheme (including the cases which require two doses), has barely reached 2% of the 1.3 billion inhabitants of the country.

Paradoxically, India is the largest global producer of vaccines and was exporting them to several countries. In order to meet the needs of its own population, the government has banned any exports from the Serum Institute of India, which produces 2.4 million doses per day of the AstraZeneca vaccine, and from Bharat Biotech, which produces the local vaccine Covaxin. This restriction, which will allow a total of 70 million doses to stay in the country, will notably affect the vaccination programs of poor countries, mainly Caribbean and African, who were the recipients of most of the Indian vaccines.

In spite of the blocking of exports, estimates by the National Institute of Advanced Studies de Bangalore (NIAS) indicate that only 30% of the population will be vaccinated by the end of 2021.

India is key for the future of the pandemic in the world

Leading virologists such as Shahid Jameel from theTrivedi School of Biosciences at the University of Ashoka forecast that the number of cases in India will greatly increase to more than 500,000 per day, which will result in the death of many hundreds of thousands of people in the next few months.

The healthcare disaster caused by the pandemic will also worsen the endemic problems of a country where only 39% of the inhabitants of rural areas have access to sanitation facilities and which struggles to eradicate open defecation. The efforts to develop the second phase of the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) program, which aims to stop open defecation and promote healthiness all around the country, have been stalled.

The We Are Water Foundation has been and continues to be committed to India, also in its fight against coronavirus. In Alwar, Rajasthan, watershed management capacity was provided to maintain community access to water during the pandemic. In Dholpur school sanitation units and drinking water systems are being built in two schools, essential to be able to maintain proper hygiene. In eight villages in the Kurnool district, Andhra Pradesh, life conditions of rural communities and students are being improved by ameliorating the accessibility to water and sanitation. The Foundation has also helped more than 3,600 plumbers, one of the groups of workers in the informal and non-organized sectors that is suffering the most from the pandemic, by providing them with training, aid kits and protective equipment to keep their jobs.

In the ever-uncertain wait for the monsoon, (May-June), India’s more than 1.3 billion people face a challenge that will be crucial to their future. Its technological sector, its production capacity and its human strength will be essential to reverse the pandemic catastrophe, but it will also be necessary to complete the profound social and health changes that have already begun. What happens in the country in the coming months will mark the history of the pandemic worldwide.