The climate crisis predictions are turning out to be true in Madagascar. Droughts have increased in the last five years and the current one is the worst in the last 40 years. The situation is particularly serious in the south of the island, where farmers lost most of their rice crops in October, a key month for the growth of the cereal, when rainfall was 50% less than the usual average.

The situation is particularly serious in the south of the island, where farmers lost most of their rice crops in October.

The devastation of the tiomena

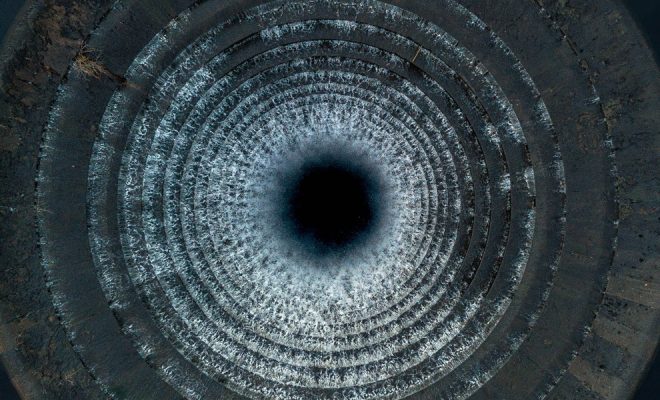

For farmers on the vast island in southeast Africa the situation worsened in January when the dreaded “red wind” – the tiomena (from tio, which means wind in Malagasy, and mena, meaning red) – devastated crops and pastures in the south. These storms, which cover the sky with a reddish dust that sometimes blocks the sunlight, contribute to increasing the dryness of the soil and deforestation. They generate a feedback loop: the more tiomena, the drier the soil and therefore the more sand to be blown by wind in the future.

For farmers on the vast island in southeast Africa the situation worsened in January when the dreaded “red wind” – the tiomena (from tio, which means wind in Malagasy, and mena, meaning red) – devastated crops and pastures in the south. © Madagascar74

This is a phenomenon that usually takes place from mid-May to mid-October, almost never in January, but the forecasts of scientists warn that these seasonal patterns will be altered by climate change.

As a result, less than half of what is needed to feed the entire population is expected to be harvested in the coming months. It is a real emergency: according to the UN World Food Programme (WFP), urgent intervention is required to avoid a worsening of the famine that has already begun, as malnutrition has almost doubled since September, from 9% to 16% of the population.

Where to go?

The short film Where to go? by Clerck, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5, shows the impact of the country’s water shortage on rice farmers, the staple food of the Malagasy people. Shortages caused by declining rainfall are compounded by the deficient supply network in villages and urban slums, increasing the sanitation and hygiene management problems already exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

57% of the population in Madagascar depends on surface water or unimproved water points for its supply. If these supplies fail, as is the case now, the population is obliged to migrate in search of areas where they can get them, greatly increasing the problem. Furthermore, Africa’s largest island presents one of the worst hygiene rates in the world, which, together with Covid-19, results in an alarming health situation.

Africa’s largest island presents one of the worst hygiene rates in the world, which, together with Covid-19, results in an alarming health situation.

Madagascar has one of the lowest hygiene levels in the world: it is among the 10 countries with the highest open defecation rate (40% of the population practices it), while only 17% has access to basic sanitation and no more than 23% of the population has basic hand-washing facilities.

In Madagascar, the Covid-19 pandemic has contributed to worsening relief services and largely silenced a very serious climate and human emergency. © Etienne

An almost unnoticed disaster

At the end of June, the WFP warned that at least 1.35 million Malagasy needed urgent food aid. Up to 80% of the population of the most devastated areas survives eating insects, such as locusts, or extracting water from cacti.

The Covid-19 pandemic has contributed to worsening relief services and largely silenced a very serious climate and human emergency. The distribution of water and food often forces people to travel up to 40 km to collect this aid, and there are many who cannot do this. This need for proximity to relief centers has increased migration from villages to urban centers, a movement that drought had started months ago.

Food concerns are now focused on the next dry season, which will start in October and end in March 2022. The WFP anticipates that this year’s food production will be 40% lower than the average of the last five years. The UN agency specifies that 74 million dollars are required for the next six months to avoid a humanitarian disaster.

The Foundationcollaborate with UNICEF in a project with the aim of improving the availability of sustainable climate resilient drinking water, sanitation and hygiene facilities in 11 communities in Madagascar. © UNICEF

Self-management of water and sanitation in the south of Madagascar

These problems have been endemic for years in the southern regions of Atsimo Atsinanana and Androy, where we are collaborating with UNICEF in a project with the aim of improving the availability of sustainable climate resilient drinking water, sanitation and hygiene facilities in 11 communities. The project will directly and indirectly benefit between 16,000 and 30,000 people among families in the communities, staff of educational centers and health officials that work in the area.

In the case of Androy, the main problem is the lack of water and the recurrence of children affected by malnutrition due to droughts. The consumption of open surface water, open defecation and the lack of basic hygiene are directly responsible for 90% of the diarrhea cases (second cause of child mortality in Magadascar) and have a direct impact on chronic malnutrition or stunting, which affects 42% of all children under five years of age.

Together with UNICEF Madagascar we apply the SANTOLIC methodology, based on the participation of the community, following the guidelines of the sustainable construction of latrines compiled in our Construction manual of latrines and wells. We follow the same protocols as in the project to sustainably eradicate open defecation in 19 communities, in the commune of Léo, in Burkina Faso.

This methodology is based on the participation of the community right from the start, both in the location of boreholes and water pumps, and in the identification of inadequate hygiene practices and the implications of those practices on health and the environment. Furthermore, community plans for the access to drinking water are developed with the direct participation of communities. In addition to building the facilities, the main objective of the project is to strengthen the communities by training them to maintain and manage them.

A community capable of managing water itself is capable safeguarding its natural capital.

This kind of emergencies increase with climate change. Effective management of water resources in line with the balance of ecosystems must go hand in hand with strong actions to curb desertification. A community capable of managing water itself is capable of reducing the risk of droughts and safeguarding its natural capital. Therein lies the hope, both in southern Madagascar and in the rest of the world.