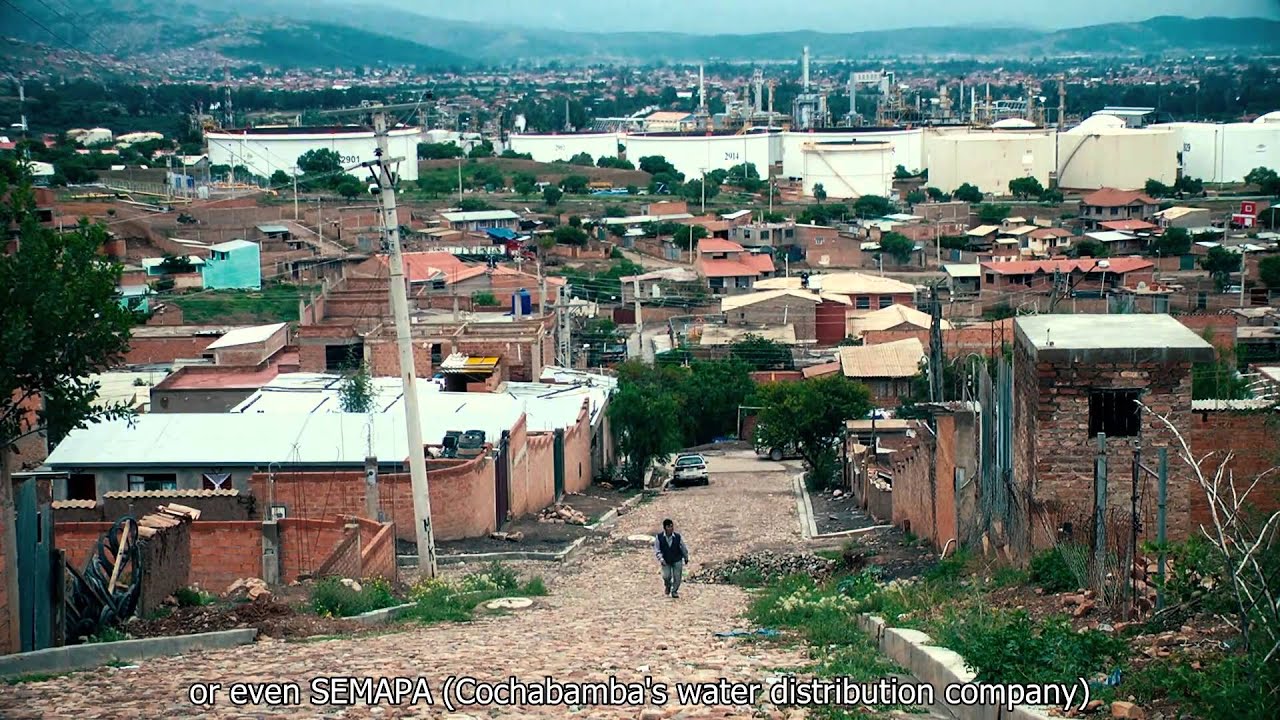

Central Itocta: after the war by Andor (Bolivia), finalist of the We Art Water Film Festival 3. Micro-documentary category.

At the beginning of 2000, thousands of inhabitants of Cochabamba, a city located in the centre of Bolivia, took to the streets to protest against the privatisation of the drinking water and sanitation services in favour of the multinational company Bechtel. The conflict reached its highest point on the 8th April, when the government of Hugo Banzer declared the state of siege. There were more than one hundred injured and a 17-year old boy died. The executives of Bechtel left Cochabamba on the 10th April, the privatisation law was revoked and the water supply returned to public hands. A legend had just been born: The Water War in Cochabamba.

Beyond the Water War and the socio-political conflicts, the fight for water in Bolivia is the consequence of a much broader problem. Nowadays, around three million people in rural areas (30% of its population) lack water security and five million do not have access to adequate sanitation. On the other hand, Bolivia is one of the most threatened countries by climate change. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) presented a report in 2013 in which it already alerted to the problems the Andean highlands would experience due to climate change, a situation that is especially unjust as it is one of the countries that emits less greenhouse gases.

Laguna Honda (in English “Deep Lagoon”) is a salt lake located at 4,114 metres (13,497 ft) over the sea level in the bolivian Potosí Department, close to the border with Chile.

© Diego Delso

The report stated that the average temperature in Bolivia was rising and could increase up to 2 ºC by 2030, and from 5 to 6 ºC by 2100. Its environmental vulnerability is due mainly to the existence of very different ecosystems and a growing deforestation. The report also stated that in the last 25 years, the Andean country had been affected by severe flooding in certain regions, caused by El Niño, combined with intense and long droughts.

As a terrible confirmation of the forecast included in this report, Bolivia was hit in 2016 by the most severe drought since the 80s, as a result of a very intense El Niño. This serious water crisis affected the cities of Oruro, Potosí, Cochabamba, Sucre and, above all, La Paz, where more than 400.000 inhabitants were left without water supply for several weeks. In the countryside, some areas in the highlands lost up to 90% of the crops and the government declared the state of national emergency. A visible example of the crisis is the drying up of the Poopó Lake located in the Oruro highlands, which is a historically unstable water mass, whose volume decreases due to the drop of rainfall.

The drought ended abruptly – also confirming the UNPD forecast – with violent flooding that started at the end of December and extended throughout the month of January.

A solid fighting spirit for a fundamental human right

Resilience is defined as the capacity of human beings to adapt positively to adverse situations. This water suffering has made the Bolivian people especially resilient to the lack of water. Central Itocta: after the war shows a beautiful example of resilience: citizen action, in view of the lack of effective political decisions to guarantee the water supply, led to the creation of “water committees.”

These associations gather the knowledge on the management of water resources, climatology and the emergency response actions and they transmit it to the community creating a solid awareness and promoting the water culture. This has allowed a new path for the recovery of the access to water in a sustainable and participatory way.

Project: Water, sanitation and hygiene in schools in the Chaco-Chuquisaqueño.

©Carlos Garriga/We Are Water Foundation

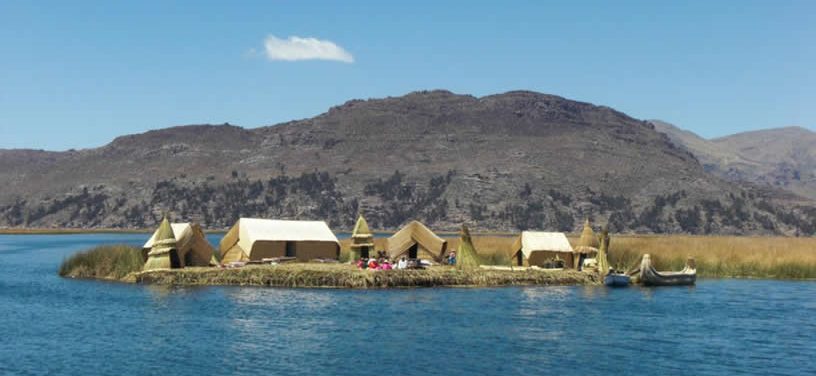

The projects developed by the We Are Water Foundation in Bolivia have an impact on these issues and are a good example of the actions needed to combat the water crisis and the lack of sanitation in the country: Water, sanitation and hygiene in schools in the Chaco-Chuquisaqueño, in collaboration with Unicef, and Ancestral culture to save the water of Lake Titicaca in collaboration with Educo. Bolivia needs to become a model from which the entire world has to learn.

Project: Ancestral culture to save the water of Lake Titicaca.

©Educo