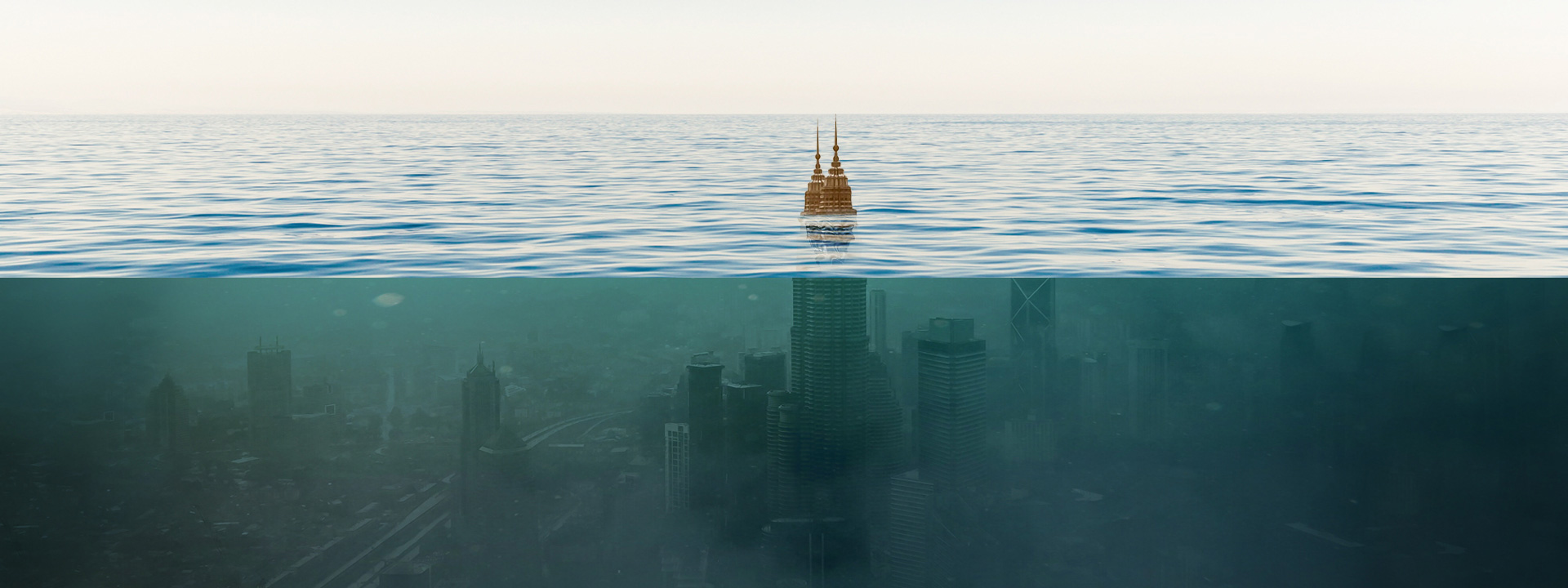

Following the COP28 summit in Dubai, the French Foreign Minister, Catherine Colonna, declared that France was willing to consider requests for climate refuge from Pacific nations compelled to relocate their population due to rising sea levels. This stance aligns with the policy adopted by the Australian government during COP27, wherein an agreement was made with Tuvalu to accommodate its residents in the event of the nation being submerged by the Pacific Ocean. The developed world is increasingly recognizing the urgent and undeniable issue of rising sea levels, which is causing significant disruptions.

Rising sea levels are leading to the first forced and planned population relocations. Small coral islands and tropical deltas face the most significant impact and are in imminent danger. © Atafu/ NASA Johnson Space Center

Climatic Statelessness?

Tuvalu, consisting of three coral islands and six atolls, hosts a population of 12,000 people within a limited territory spanning 26 square kilometers, with an average elevation of merely five meters above sea level. Over the last decade, Pacific waters have encroached upon its shores, resulting in the salinization of crops, the collapse of homes, and the depletion of freshwater resources. Tuvalu’s current predicament aligns with the projections outlined in the latest IPCC report, and experts in the scientific community anticipate the complete disappearance of its territory by the end of this century.

The culmination of such a catastrophe would signify more than just the physical disappearance of Tuvalu’s territory; it would lead to the cessation of Tuvalu as a state. The inhabitants, in the absence of a tangible homeland, would be rendered stateless, introducing a new dimension to the legal challenges surrounding climate-displaced persons. Adding a dramatic twist to the situation, Simon Kofe, its foreign minister, declared during COP27 the intention to create a virtual replica of Tuvalu. This initiative aims to preserve the country’s landscapes and culture in anticipation of the likely submersion of the islands. If a legal framework for this innovative concept can be established, Tuvalu could become the world’s first “digital nation.”

Low-lying Coral Islands

Recently, numerous small island states, including Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands, and the Cook Islands in the Pacific, have raised concerns regarding maritime encroachment. The shared challenge among these nations stems from their coral and, in some cases, volcanic structures, resulting in low elevations above sea level. The absence of significant high ground leaves them vulnerable to permanent flooding or the impact of severe storms.

The Maldives, a globally acclaimed tourist destination in the Indian Ocean, has been a prominent case since the 1970s when its government initiated the relocation of its coastal population in response to rising maritime encroachment. The archipelago, comprising 1,192 islands, with 188 of them inhabited, has vividly demonstrated its vulnerability to the growing frequency of high wave episodes.

Malé, the capital of Republic of Maldives, with a population exceeding 100,000, is surrounded by protective dykes that have proven insufficient in halting the encroachment of water. © Shahee Ilyas

On these islands, the average elevation of the land ranges from 0.5 to 2.3 meters above sea level. The capital, Malé, with a population exceeding 100,000, is surrounded by protective dykes that have proven insufficient in halting the encroachment of water. Consequently, the government opted to construct an artificial island, Hulhumalé, using sand elevated by nearly two meters. This new landmass is designed to accommodate almost 555,000 people and is connected to Malé by a one-kilometer-long bridge. Additionally, a project has been initiated to create around 5,000 floating homes on pontoons anchored off the capital.

In the Atlantic region, Prime Minister Phillip Davis of the Bahamas presented scientific reports during COP28 illustrating the exacerbation of damage caused by hurricanes and tropical storms due to rising ocean levels and coral degradation. He urged the international community to address global and oceanic warming promptly.

The Unavoidable Relocation to the Mainland

Meanwhile, relocation initiatives to the mainland are actively underway in numerous affected countries. In Panama, the approximately 1,300 residents of the small island of Gardi Sugdub, situated off its Caribbean coast, eagerly anticipate what is evolving into the first officially recognized case of climate refugees in the Americas. Scientific reports indicate that much of the San Blas archipelago, to which the small island belongs, is likely to face a similar fate. Despite this, the government’s scheduled relocation program to the mainland is facing ongoing delays.

In the small island of Gardi Sugdub, in Guna Yala northeast Panama, the indigenous Kuna community residing on the island has been grappling with the challenges posed by flooding, which has made their lives increasingly difficult. © Lee Bosher

For years, the indigenous Kuna community residing on the island has been grappling with the challenges posed by flooding, which has made their lives increasingly difficult. The inundation has led to the deterioration of water sources, rendered schools unusable, and resulted in environmental pollution due to inadequate sanitation facilities.

Damage Begins Before the Flood

Sea level rise represents a gradual and persistent threat, with land submergence serving as the ultimate consequence. As the sea surface elevates, the heightened risk of storm surges becomes apparent, resulting in tangible consequences such as the salinization of drinking water sources and crops, the disruption of power grids, and the destruction of homes and coastal defenses.

Though not immediately apparent to the naked eye, the harm inflicted on coral is a significant concern for scientists due to the potential crossing of another critical environmental tipping point with severe consequences. Corals, already facing damage from acidification and elevated temperatures, thrive best when situated near the sea surface. If the rate of rise in sea level surpasses the corals’ capacity for vertical growth, they will find themselves in suboptimal conditions for development, posing a significant threat to their sustainability.

The Tropics, the Most Endangered Area

The projected average sea level rise, anticipated to be between 60 and 80 cm by the end of this century, is poised to have particularly adverse effects on Earth’s tropical regions. These findings stem from a study published in Nature, which leverages data from the first high-precision global elevation model. This model incorporates data from the ICESat-2 (Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2) satellite, launched by NASA in 2018. The satellite measures the elevation of various Earth surface features, including glaciers, icebergs, forests, and other elements.

The study highlights a concerning fact: 62% (649,000 km2) of land area situated at an elevation less than two meters above mean sea level is concentrated in tropical regions. It’s worth noting that, according to UN estimates, the population residing in areas exposed to sea level rise was 267 million in 2020. Projections indicate a significant increase, with an expected population of 410 million by 2100, with 72% of these individuals living in the tropical belt. This presents a substantial risk of triggering a severe humanitarian crisis.

In addition to islands, deltas are emerging as areas of significant concern, particularly in South Asia, where they serve as the mainstay of food security for tens of millions of people. The convergence of factors such as advancing seawater, escalating irregularities in rainfall, degradation of mangroves, and pollution collectively contribute to the decline of the habitat within these intricate ecosystems. This degradation poses a threat to the farming communities dependent on these deltas.

Adaptive Solutions Are Urgent

Scientific projections indicate that halting the rise of sea levels is challenging, primarily requiring the prevention of polar melting and ocean warming. This, in turn, is contingent on significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. While mitigating the root causes remains a critical long-term goal, the urgency lies in adaptive measures. In this context, there is considerable room for action, as the relentless advance of the sea leaves few alternatives to relocating the affected population.

Indeed, the need for new adaptation strategies is evident. This includes promoting the cultivation of less water-intensive crops and prioritizing the preservation and nurturing of mangroves and coral environments. © LuqueStock / Freepik.

In the Maldives, various technological solutions have been developed as alternatives to address the challenges of rising sea levels. These solutions primarily involve raising protective dikes and constructing artificial islands. However, there are practical limitations as it is not feasible to encompass the entire perimeter of all threatened islands, and the required investment is prohibitively high. Moreover, while these measures protect human infrastructure, they do not address the broader ecological concerns, such as the damage to corals and mangroves.

Indeed, the need for new adaptation strategies is evident. This includes promoting the cultivation of less water-intensive crops and prioritizing the preservation and nurturing of mangroves and coral environments. While these solutions offer long-term benefits, their implementation is imperative. This, in turn, calls for substantial investments in scientific research and the comprehensive collection of data related to coastal land surfaces.

Some ecologists view our struggle with sea flooding as a metaphor for humanity’s broader failure in addressing climate change. The immediacy and substantial magnitude of the challenge underscore the urgent need for adaptive measures to cope with the current impacts and to mitigate the accelerating consequences in the decades ahead.