Droughts increasingly occur in higher latitudes. This fact can be observed throughout the Earth’s subtropical belt, but it is becoming an economic and environmental disaster in some areas. For example, in the western Mediterranean Basin, countries such as Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy face an unprecedented situation leading to a worrisome future.

The IPCC forecasts continue to be fulfilled, and droughts are affecting regions where they were rare. © World Meteorological Organization

Spain: drought after drought

The case of Spain is particularly severe. Last year was the hottest and one of the driest in its history. The winter rains and snowfalls have not provided water reserves, and the first half of spring is proving catastrophic. In April, one of the wettest months of the year, all the negative records have been broken: less than 15% of the usual rainfall and high temperatures have reached an average of 10ºC above normal in most observatories. With almost the entire cereal crops lost and the irrigation of its orchards compromised, Spain finds itself with reservoirs at half their capacity and many aquifers showing signs of depletion.

In some areas, such as the internal basins of Catalonia, which supply more than 6.5 million inhabitants, the water stored in reservoirs does not reach 26% when the average level for the season is 80%. As a result, more than 200 Catalan towns are planning restrictions, there has been a reduction of 40% in the water used for agriculture and 15% for industrial uses, and in public parks, water is only used to irrigate trees in danger of dying.

The situation exceeds all forecasts in the country’s south, where they are more accustomed to drought. The Guadalquivir basin also has its reservoirs at 25%, while the average of the last ten years (also with drought prevalence) is 63% in April.

The situation is complicated and worrying since the National Meteorological Agency (AEMET) reports that even if the climatically average rainfall is reached in the second half of spring, it would not be sufficient to recover the water shortage in the country’s basins. The forecasts do not even point to the rainfall recovering to statistical normality.

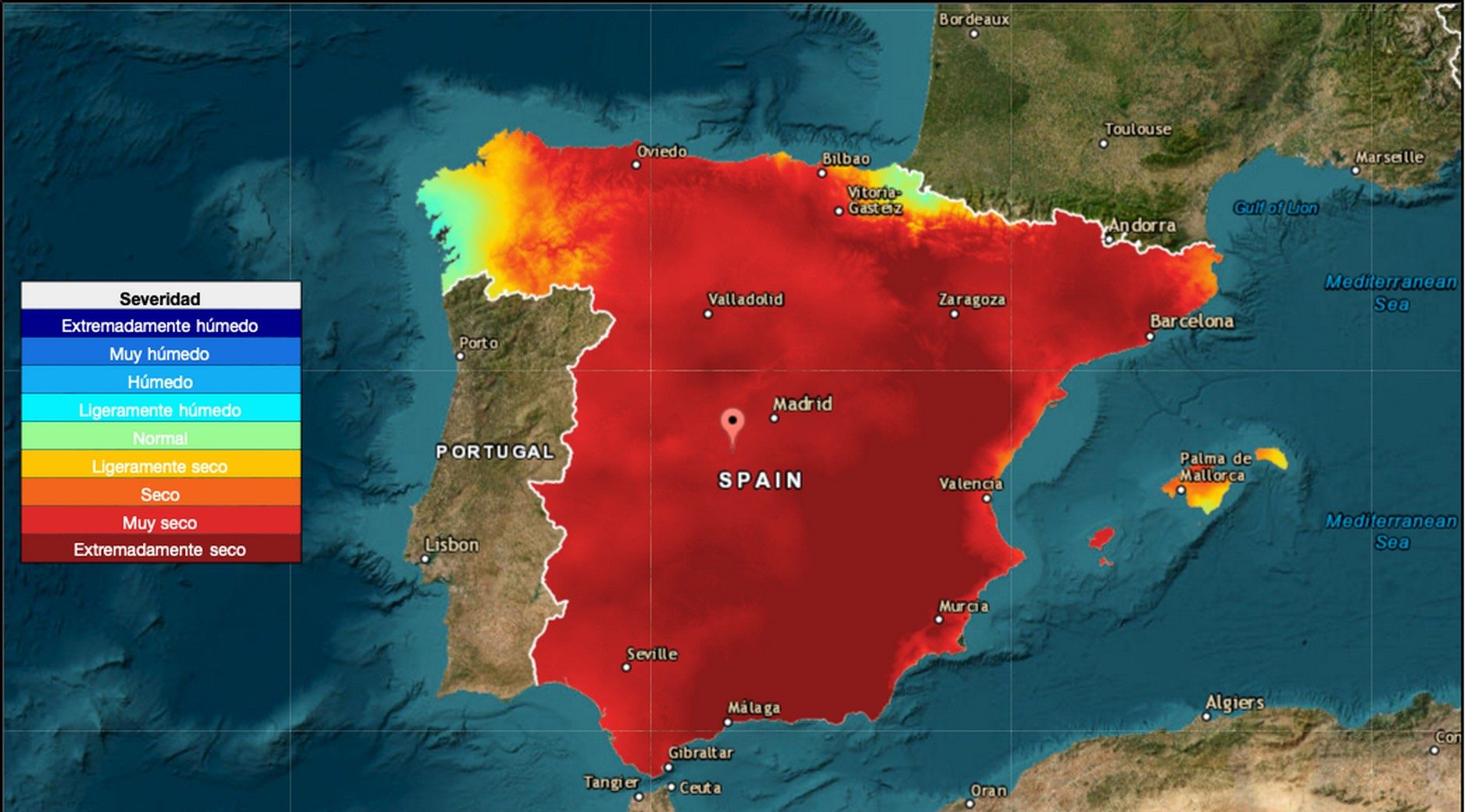

With this situation, the summer heat and the usual tourist avalanche will increase water stress to unpredictable levels. The situation is so exceptional that the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) has provided a real-time drought monitor to follow the evolution of soil moisture.

Snapshot of the soil moisture map in Spain in April, according to the CSIC monitor

With many crops lost and supply threatened in many communities, Spain faces significant economic impacts. The European Central Bank (ECB) warns that extreme weather events would lead to an increase in the ratio of public debt to GDP of around 5%. In contrast, in other northern countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium, the increase would be only 1%.

France, Italy, and Morocco face unprecedented situations

The south of France has experienced an exceptionally dry winter. Météo-France, the national meteorological service, has recorded the longest winter drought since they started collecting data (1959): 32 days without rain. In the first half of spring, snowfall in the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the Massif Central has also been much lower than usual for the season, and hydrologists fear that there will be exceptional water stress this year. On social networks, the French have shown their amazement at the situation, sharing thousands of photographs of dry rivers and lakes.

As in Spain, forecasts for the summer predict dryness. It is such an unusual situation that it catches France off guard. On March 30, the Government presented the Water Plan and, in the south of the country, in mid-April, a dozen départements issued decrees banning the filling of private swimming pools.

Northern Italy, a usually wet region, is also experiencing a situation similar to the French one. The last time the country had two consecutive years of drought was between 1989 and 1990; however, according to the Aeronautica Militare meteorological service, the lack of rainfall occurs under much more adverse conditions than in those episodes, as it follows several years of low rainfall.

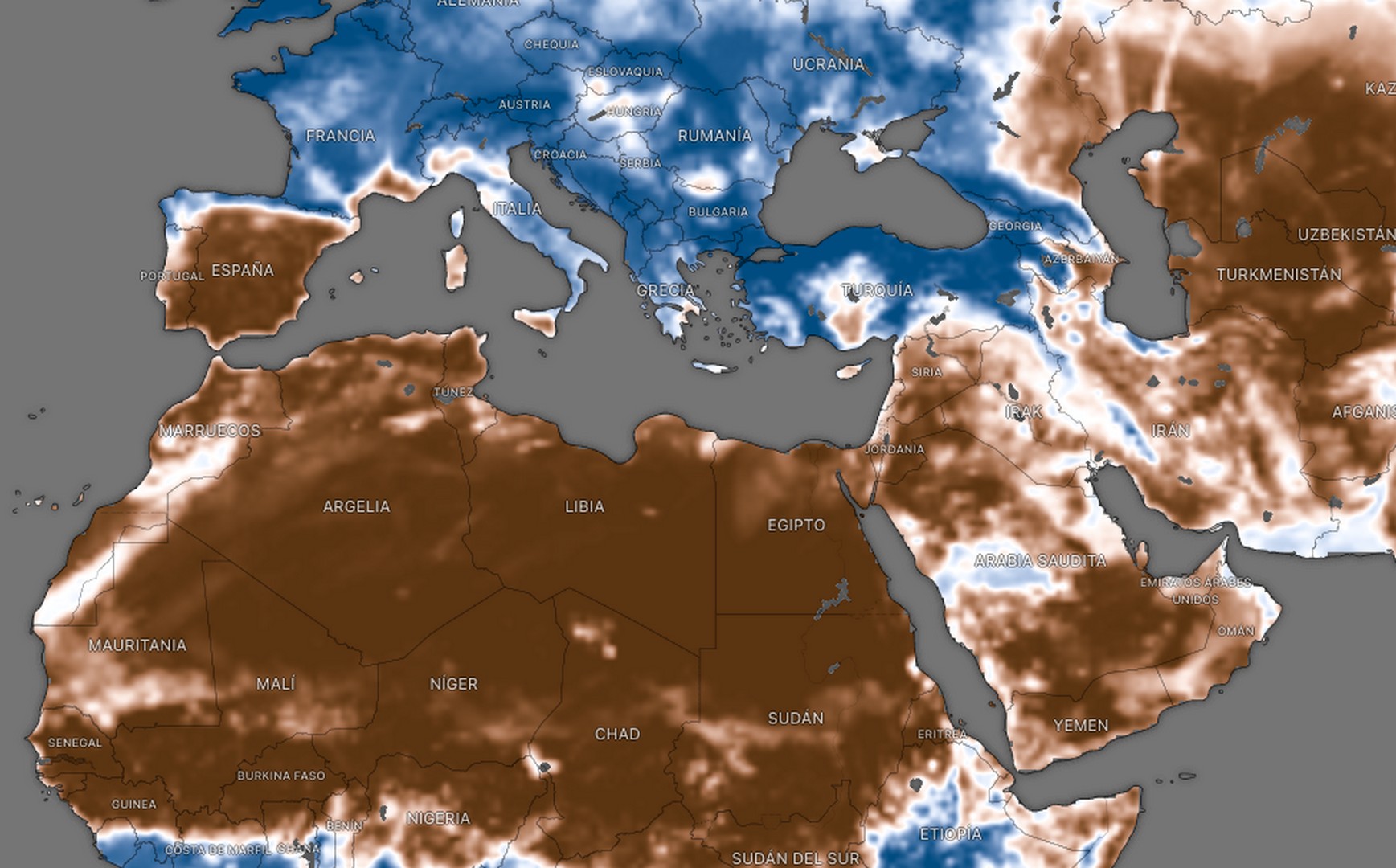

Soil moisture in the area surrounding the Mediterranean basin, 27 April 2023. From blue (wetter) to brown (drier).

The scarce winter snowfalls have caused insufficient snowmelt to nourish the Po River basin. As a result, many farmers are considering abandoning traditional corn and soybean crops and planting sunflowers, more drought-resistant plants.

In the south of the Mediterranean Basin, the lack of water has also reached Morocco’s cultivated areas, one of the most competitive in the European market, currently suffering from the worst drought in the last 30 years. In a country where the agricultural sector accounts for 15% of GDP and employs between 40 and 43% of its workforce, the government has set up a plan worth millions to combat water shortages. In turn, the Moroccan National Council for Human Rights has warned that the conflict between the priority of providing drinking water and the promotion of agricultural activities should not affect the rural sector and cause the displacement of people to the cities, as is usual in these crises.

The usual tensions for an inspiring reaction

Spain offers another example of the many sides of the water problem. The drought comes at a difficult time for the Government, which is engaged, as usual, in the eternal debate on water and the agricultural model. Moreover, the Mar Menor crisis has been joined in recent weeks by the exploitation of the depleted aquifers of the Doñana National Park, a very tense political dispute in which the European Commission has even intervened, advising against the agricultural plan of the Junta de Andalucía (the autonomous government of the region) and threatening sanctions if the project goes ahead.

Tensions between farmers and governance are common in the face of water shortages and are not exclusive to Spain. They occur in almost all dry countries in the subtropical belt of the Earth, the most threatened, according to IPCC reports, with alterations in rainfall. However, in the USA, the problems caused by water management in California, which are now spreading to other southern states, stand out.

This situation destabilizes food markets, and the war in Ukraine adds to the upward price trend. In these cases, as we have seen in recent months, the most affected are always the countries with the weakest economies, in which droughts, in addition to affecting their GDP, provoke devastating famines with thousands of deaths and displacements.

Moreover, the Mar Menor crisis has been joined in recent weeks by the exploitation of the depleted aquifers of the Doñana National Park. © Ángel M. Felicísimo

The tension generated in the European countries of the Mediterranean Basin is unprecedented. It has the potential to create a new climatic map for countries located north of Africa, a new transitional frontier towards the more humid areas of the North. Therefore, the reaction of governance must be radical, swift, and coordinated among all the countries to agree on aid, balance the food markets and, above all, activate efforts to mitigate global warming as much as possible.

It is essential to do this to be able to build a baseline for the uncertain future that lies ahead. This alarming situation provides the impetus for civil society in rich countries, aware of the seriousness of a problem that directly affects their lives, to press for changes in water management models and to decide on more realistic actions to mitigate global warming urgently. The planet’s subtropical belt, where the most populated regions reside, urgently needs it.