The process, already started in agriculture and industry, will need to be extended to the domestic water network. We have the necessary technology to do it, but there is a cost we all need to reduce if we become aware that the most vulnerable and precious resource we have flows through our pipes. To be able to understand the circular economy approach inspired by nature might help us to do so.

The fact of advancing towards a sustainable future implies that sooner or later we will need to reuse water in those areas with greater water stress, the number of which continues to increase around the world. To achieve the reuse of water is a part of the transition model from a linear to a circular economy, a transformation of the economic activity towards sustainability that we need to face if we wish to obtain a planet where all of us can live in dignity.

We have lived in relative comfort until now with the linear model of “producing, using and throwing away” that has led us to a situation near collapse: many resources are exhausted and the levels of residual contamination have caused the start of a climate change that has become a primary international concern.

The circular model stands for “reducing, reusing and recycling.” It is inspired by the dynamics of nature where there are no such concepts as raw material or residue: all elements within the natural cycles perform a specific function, carrying out a continuous reuse. The circular economy aims to reduce the consumption of raw materials, water and energy in the manufacturing of consumer goods. The transition towards this model is inspiring institutions and a larger number of corporations, which see this as an opportunity for a sustainable economic expansion, thus acting to prevent the temperature of the planet from increasing more than two degrees before the end of the century.

The transformation cycles in nature do not generate waste nor do they consume raw materials. ©Antonio-Marín

When water stops being a renewable resource

Water is in the eye of the storm of the sustainable revolution. It is an over-exploited resource, especially in those countries that are more threatened by climate change potentially, such as the Mediterranean ones and in large areas of Africa, Asia and South America. The European Environment Agency (EEA) points out that the exploitation rate of water resources should not be over 20%. This percentage is exceeded in many river basins in European countries and to a greater extent in the Mediterranean ones, where during the summer more than half of the population (53 %) lives in a situation of water stress. In Spain, for instance, the equivalent to 29.2% of the resources in rivers and aquifers was spent in 2013, nearly double the average of the EU.

Nowadays we obtain water with certain processes structured within the linear economy: we obtain water from rivers and aquifers and return it purified to the environment, or rather, with an “acceptable” level of contamination so as not to damage the environment. Until recently, we had the idea that water was a renewable resource that nature would always provide us. But now we know this is not true. More water is spent than it is renewed in many areas around the world.

Heading toward reuse

In this video, Damià Barceló, of the Instituto Catalán de Investigación del Agua (Catalan Institute of Water Research-ICRA), explains the process of water purification and its reuse:

In this context, the concept of reuse becomes more relevant. As pointed out by Barceló, “the total reuse of water, in order to return it to rivers as drinking water or to return it to the water supply system will be a way of avoiding the negative effects of the droughts we suffer. There are countries such as Israel or Singapore that reuse 100% of their water. This is the path to follow.”

We already recycle water for agriculture, which is the activity that consumes more drinking water around the world: 69% of the extractions. ©Sebastian Liste/NOOR for FAOp

Agriculture is the sector that consumes more water -69 % of the drinking water extracted around the world is used to water plants– and it is the one that is receiving the most reused water. This is mainly due to the fact that water for irrigation needs a purifying technology that is less expensive as its reuse parameters are less demanding that those in the municipal water supply systems.

Domestic consumption, which takes up 12% of the extractions of fresh water, experiences, as well as the agricultural consumption, spectacular seasonal variations that are usually simultaneous, creating demand peaks that cause great availability problems. Spain, for instance, receives more than 55 million tourists every year, most of them concentrated in the summer season, which is precisely when agriculture demands more water. The threats of climate change create more uncertainty and impose a design of infrastructures and technologies that are able to operate in droughts or floods. According to Barceló, this will affect the reuse of water: “We might go through times with nearly no water and other times with water in excess; therefore, the water treatment plant will need drainage systems that work well and it will be necessary to prepare the piping system for extreme situations.”

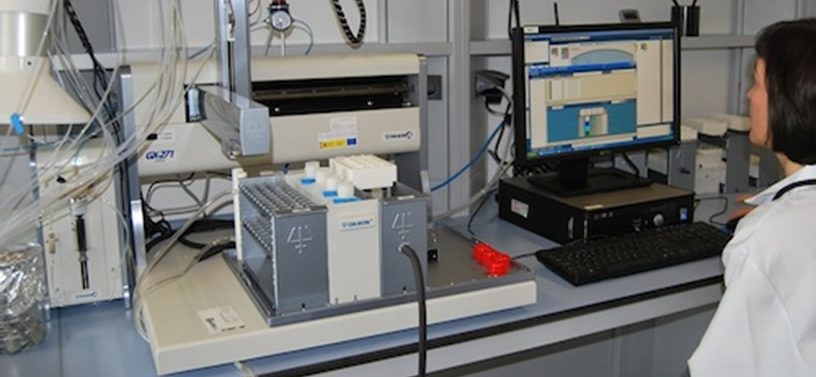

The maintenance of the quality of water implies constant research. This is the key to the success of its reuse. © ICRA

A cost we need to bear. Are we aware of this?

The reuse of water is not a technological problem. There are efficient systems that allow the recycling of water to make it drinkable. These systems allow the reuse of waste to obtain other raw materials such as fertilizers or other products; the main problem is the cost. According to Barceló if we wish to return the purified water to our distribution network, we need to assume additional costs that have not been contemplated until now: “The cost of reused water for domestic use would be very similar to that of desalinated water. But we need to assume it and the investments carried out in this field will finally have an effect on the pockets of taxpayers.”

We are generally used to paying little for water and any measure that tends to increase the price of the monthly bill is tremendously unpopular; even, and this is paradoxical, in countries such as Spain, where it seems that citizens are not aware of what it means to open the tap every day in a country ravaged by barrenness and over-exploitation of aquifers. As noted by Alejandro Maceira, director of iAgua, in a recent debate, “we experience a daily miracle in Spain: to have high quality water 24 hours a day and 365 days a year.”

The fact of drinking once again the water we released into the sewer system might create a psychological reluctance in many people, but at the same time it might be a wake-up call to raise awareness of the value of water, of the importance of not wasting it and above all of preventing its pollution. In this sense, the emerging pollutants, which are constantly detected, are the main enemy of the total reuse of water as they force a constant research to detect them and in technologies to eventually eliminate them.

“If we wish to have high quality water, we will need to pay for it”, the director of ICRA points out, “it will need more treatments, more controls and someone will need to assume this, the Administration may take up a part of this cost, but the rest will need to be paid by taxpayers.” In view of the unpopularity of these measures, Barceló thinks that this reflection will prevail, based on the paradox of many people spending half of their salary in buying a mobile phone and being outraged if the water bill is increased in one euro per month. “As citizens we need to decide what is necessary and what is not so necessary. Having a new mobile phone that takes better pictures and has more memory might not be as necessary, while water really is necessary.”

Water is too precious to use it only once. We need to become aware and consider that the benefits of a culture of reuse and recycling can help us greatly. In agriculture, to advance towards eco-friendly models will decrease ground water contamination caused by fertilizers; in industry, we will reduce and recycle waste, and in our homes, if we eliminate the pollutants we pour into the sewage system we will reduce the cost of reuse. To understand the economy model inspired by nature cycles will guide us towards global sustainability. The health of water and its availability will indicate if we are achieving it.