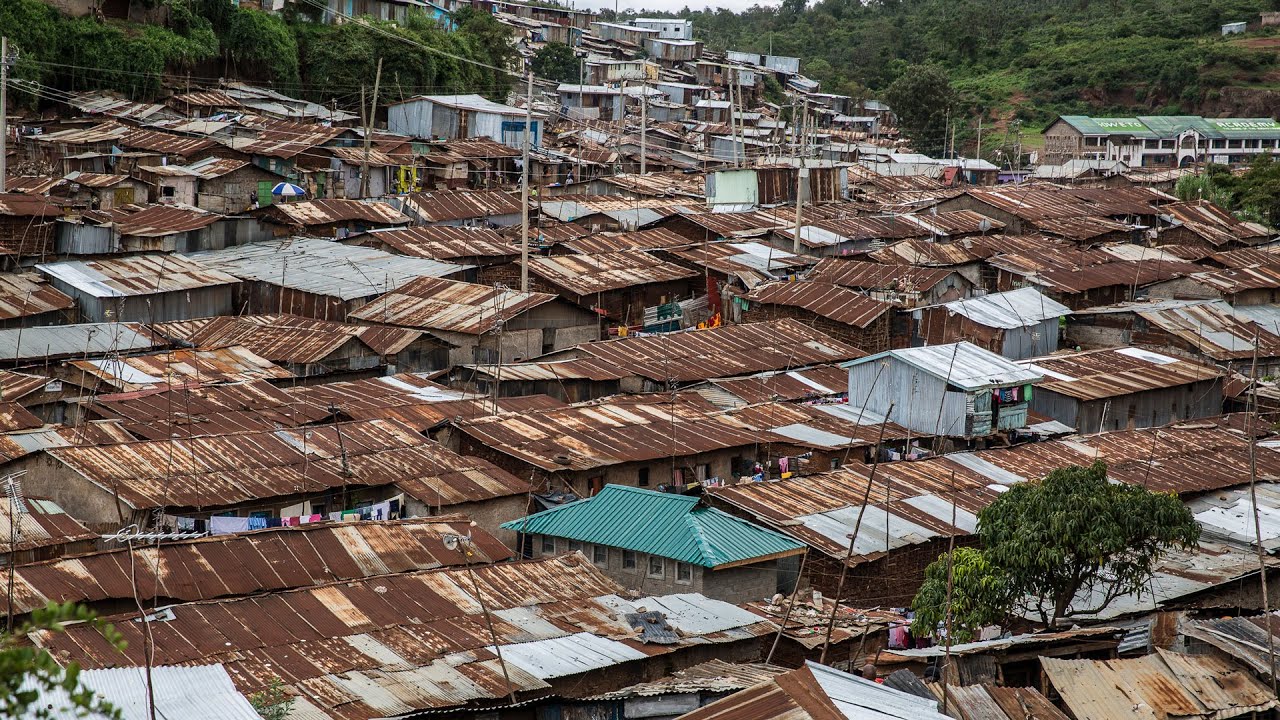

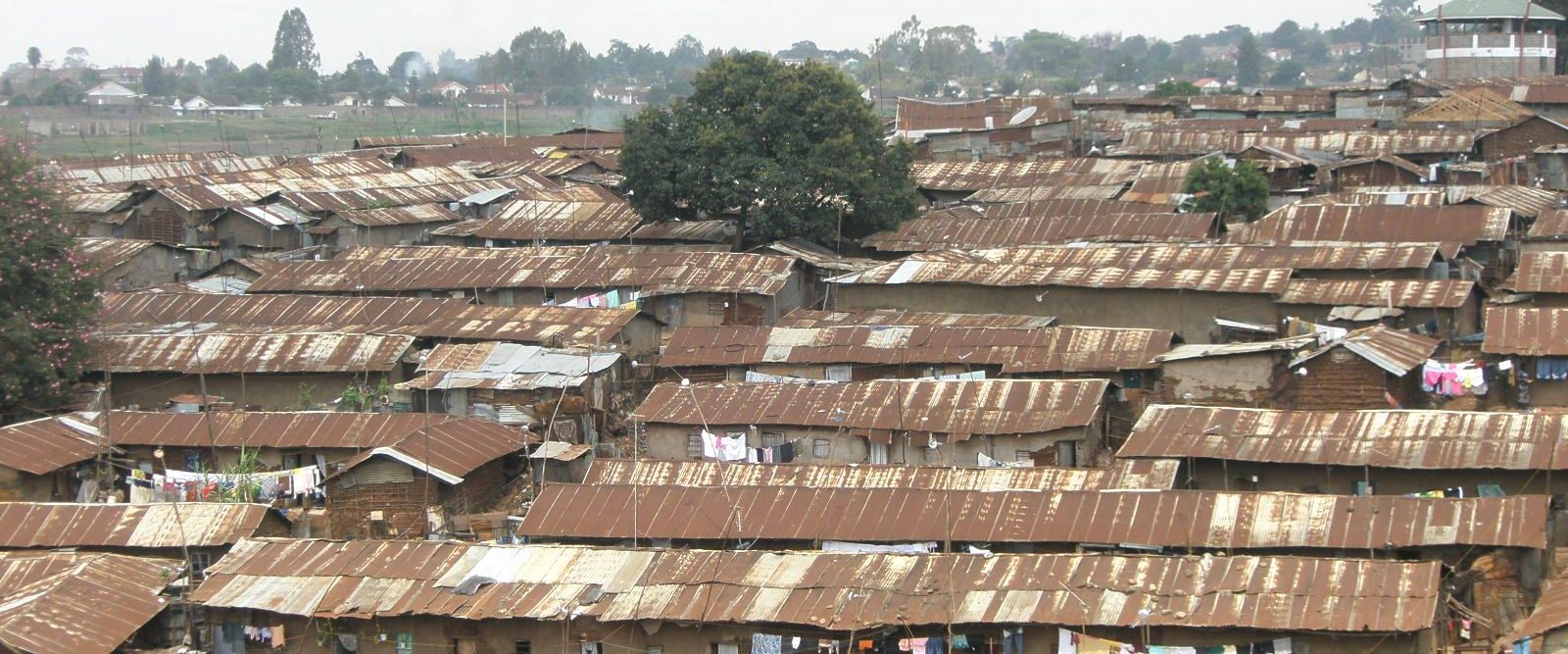

During the month of April, residents in Kibera, the poorest slum in Nairobi, have an additional concern for survival: repairing the leaks that flood their precarious shacks with dirt floors and tarpaulin roofs. April is the rainiest month, but so are May, November and December. However, spring and autumn showers allow many to collect fresh water, a treasure in what has been Africa’s largest slum for decades.

In Kibera, as in almost every slum around the world, it is virtually non-existent ©Ninara

This is not the case of Mitchel and Angle, protagonists of the short film Raindrops by Stephen Okoth, finalist in the micro-fiction category at the We Art Water Film Festival 5. This piece recalls a real story that took place in Kibera during one of those November downpours. Mitchel tries to bail out the water that floods his shack while taking care of his sister Angle, who eventually falls ill to pneumonia.

Raindrops, short film by Stephen Okoth (Nigeria). Finalist in the micro-fiction category at the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

Angle recovered, but the fate of other children in Kibera and in other slums worldwide is linked to diarrhea and pneumonia, endemics mainly caused by the lack of drinking water and sanitation, inseparable scourges in marginal urban areas. According to UNICEF, these two diseases cause 151 child deaths for every 1,000 live births in Kenya.

During the month of April, residents in Kibera, the poorest slum in Nairobi, have an additional concern for survival: repairing the leaks.

Sanitation? This is a slum

Until recently, Kibera had no water and it had to be collected from the Nairobi Dam, adjacent to the neighborhood. Water from the dam, degraded by waste from the slum, has been the reason why typhoid fever and cholera have become endemic in the suburb. There are now two supply pipes from a water treatment plant: one built by the Nairobi municipality and the other one by the World Bank. Residents get water at three KES (around $0.03) per 20 liters. It is an affordable price; however, for those who live with less than two dollars per day, rainwater allows them considerable savings for better survival.

Until recently, Kibera had no water and it had to be collected from the Nairobi Dam, adjacent to the neighborhood.© Ninara

The sanitation situation is worse. As in almost every slum around the world, it is virtually non-existent: the number of shacks has increased in an uncontrolled and almost always illegal manner, which has led to the inhibition of the government and the municipality to provide a sewage system. Toilets can only be found in older buildings: in the rest, a latrine is shared on average by up to 50 shacks. Once full, teenagers take turns emptying them and transporting its contents to the Motoine-Ngong River. This watercourse, which used to be the main source of clean water for the Nairobi Dam, has become an open sewer that also receives tons of garbage generated by Kibera.

The uncontrolled growth of the neighborhood has prevented the installation of the most basic sanitation system. There has not been any interest from the government to do so. One of the most effective current actions is carried out by Umande Trust, an organization established in Kibera in 2002 with the specific aim of solving the serious sanitation problem of the neighborhood. Its project has been based on the construction of 19 “bio-centers”, facilities where people can defecate in safe latrines and where they can find clean water and showers.

Waste is discharged into an underground tank built under each building. Biogas is obtained from it, which is channeled towards a communal kitchen available for people to cook with drinking water. The remaining waste, anaerobically digested by microorganisms, is removed from the tank once every year and sold as agricultural fertilizer. The profits are invested in the community, managed by a committee chosen among users of each bio-center. Umande Trust is implementing this type of facilities, entirely lead by the community, in other slums in Kenya.

The rehabilitation of the Motoine-Ngong river is part of a the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) project, which encompasses all waterways that supply water to Nairobi. All of them have been polluted by the capital’s slums, which has already experienced several water supply crises that climate change and demographic growth threaten to worsen.

There are no exact data available, but UN Habitat indicates that in Kiberathat eight or more people live in shacks that are rarely larger than 12 m2. © Antonella Sinopoli

From virgin forest to slum

The history of Kibera can be considered paradigmatic of the origin of most of the run-down neighborhoods present in the cities of sub-Saharan African countries.

Kibera, in the language of the Nubians, means “forest”, and that is what it was at the beginning of the 20th century: a virgin forest of around 4,000 hectares, about five kilometers from the center of Nairobi, Kenya’s capital. In 1912, the British colonial government decided to parcel it out to pay for the services of Nubian soldiers of Sudanese origin who had belonged to the King’s African Rifles. It was a regiment that served the British Crown in World War I and in the maintenance of its possessions in East Africa from 1902 until the end of the colonial era in the 1960s.

Many Nubians sold their land, mostly to the Kikuyu, the majority tribe in Nairobi, and others settled on their plots. The forest began to be populated by absorbing poor tenants from the city until 1928, when the British transferred Kibera to Nairobi’s municipality. The Nubians were considered settlers for land ownership purposes and were progressively deprived of their rights with many of their plots passing into municipal hands. This was the start of the degradation of the land, which was accentuated by Kenya’s independence in 1963. In 1965, the neighborhood had 6,000 residents; in 1980, 62,000, and in 1998 half a million. Kibera became a destination for migrants fleeing rural poverty, ethnic conflicts and constant wars in neighboring countries.

According to UNHCR, the main countries of origin of migrants to Kenya in 2019 were Somalia (43.35%) Uganda (29.62%) and South Sudan (8.50%). This flow of displaced people mostly ended up in the slums mixing with Kenya’s domestic migration from the country’s rural areas. There are no exact data available in Kibera, but UN Habitat indicates that eight or more people live in shacks that are rarely larger than 12 m2. The rent for these precarious dwellings, with no water or electricity, can reach 700 KES ($6.50) per month.

No one knows how many people live in Kibera, whose annual growth rate reaches approximately 17%. Estimates range from the 250,000 declared by the government to one million announced by some NGOs. UNHCR and UN Habitat estimate that some 2.5 million people, 60% of Nairobi’s population, live in different slums that take up less than 6% of the residential land in the capital, including Kibera.

Ending slums is an international obligation.

Out of work because of the pandemic

Officially there have been around 2,100 deaths due to Covid-19 in Kenya, although some experts believe that the real numbers could be much higher than that. The lack of adequate healthcare services contributes to the inaccuracy of data on the spread of coronavirus. What is clear is the negative economic impact the lockdown restrictions have had on its population. Nairobi’s industrial area, close to Kibera, employs up to 50% of the available labor force, generally in low-skilled jobs. This is the basis of the cash inflow in the neighborhood, a source of income that has been severely depleted. The pandemic has also cut short the training and education programs for the youth, the most conflict-ridden and violence-generating community of the unemployed, whose disputes are added to the numerous existing tribal conflicts.

Kibera needs water, sanitation, electricity and healthcare, but what it needs most is effective governance that adequately manages land tenure rights, provides education, employment and guarantees safety. Ending slums is an international obligation. They are a symptom of social, economic, political and cultural imbalances that hinder the path towards the SDGs. In a world of ever-growing cities, avoiding the human degradation of overcrowded slums is an ethical and environmental imperative. Governments must be helped, but they are also obliged to end the neglect and concealment of a painful injustice.