In 1975, the Spanish government, then the sovereign power over Western Sahara, handed over the territory – the “last colony of Africa” – to Morocco and Mauritania, leaving the Sahrawi people’s aspirations to create their own independent state unsupported. After the Spanish withdrawal, war broke out in 1976 between the Polisario Front, the advocates of independence, and Morocco and Mauritania. In 1979, Mauritania renounced its territorial claims and signed a peace agreement with the Polisario Front. A ceasefire agreement with Morocco was reached in 1991.

Since then, the failure of UN-led mediation on Sahrawi self-determination and Morocco’s occupation of the populated areas have paralyzed a situation that the UN and the European Union itself considered “difficult to resolve.” In March, the Spanish government’s recent decision to support Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara, which the Alawite kingdom put forward in 2007, has thrown further uncertainty into the only African territory with an unresolved political status.

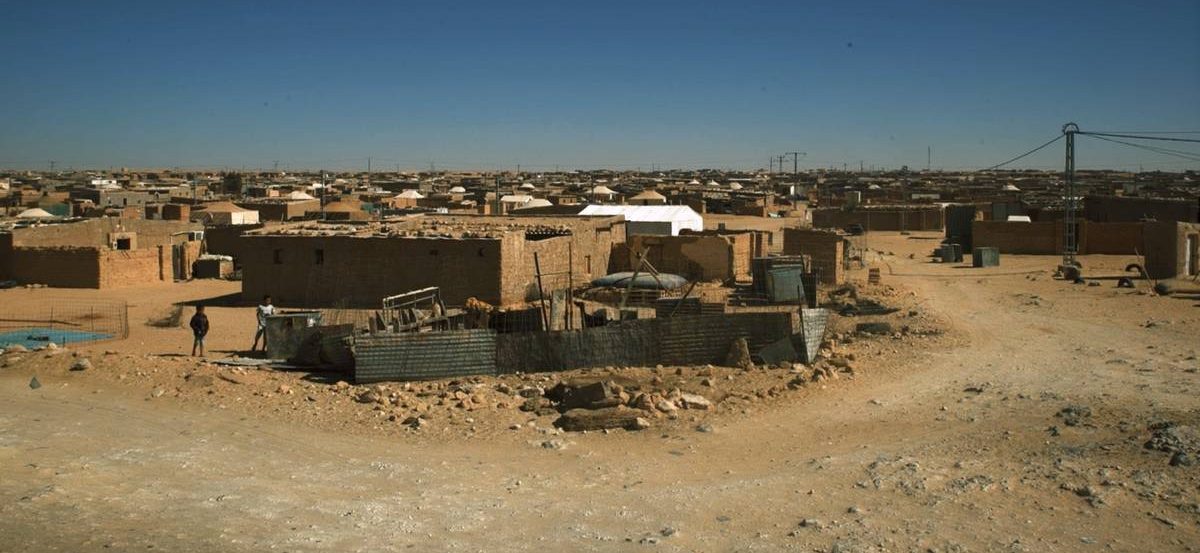

More than 173,000 people, according to UNHCR, live in conditions of poverty and vulnerability in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria.

Three generations of refugees in the Algerian hamada

This shift by the Spanish government has once again reminded public opinion of the plight of more than 173,000 people who, according to UNHCR, live in conditions of poverty and vulnerability in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria. A forgotten refugee crisis, dating back to those who fled the war at the end of 1975 and who, after 47 years, have raised up to three generations of descendants who do not know the land for which their fathers and grandfathers fought, for which they were expelled or fled. Their refugee situation is thus one of the longest-running in the world.

Thousands of women, children, and older adults fled the war and settled in the Algerian border hamada. The hamada is one of the harshest climatic zones in the world: “May Allah condemn you to live in the hamada” is an ancient curse in the culture of the nomadic Bedouin peoples of the Sahara. Thousands of broken families ended up there seeking refuge, carrying what they could, some with their tents on their backs, most ending up in camps where they had to build precarious mud houses. With no services, they have had to rely on external aid for food and water and have had to build rudimentary latrines since they began an exile that continues to this day.

Thousands of women, children, and older adults fled the war and settled in the Algerian border hamada, most ending up in camps where they had to build precarious mud houses © Western Sahara

The eternal struggle for water and hygiene

The Algerian government settled the refugees in five camps in the Tindouf hamada, named after towns in Western Sahara: Boujdour, Dakhla, Laayoune, Auserd, and Smara. When the camps were first set up, finding water became a severe problem due to the excess of salt and iodine in the wells and the lack of treatment of the little water that did exist in Tindouf. Most refugees came to rely mainly on water trucking and UN food deliveries, and this is still the case more than four decades later. The water transported today is groundwater, drawn from deep wells, in some cases just outside the camps, and in other cases several kilometers away.

In 2019, a few months before the coronavirus pandemic, UNHCR conducted a nutrition survey that revealed a worsening of most indicators, particularly those related to chronic malnutrition. Some 7.6% of the population was acutely malnourished, and 28% was stunted. 50% of children and 52 % of women of reproductive age were anemic.

When the camps were first set up, finding water became a severe problem due to the excess of salt and iodine in the wells and the lack of treatment of the little water that did exist in Tindouf.

The pandemic: Where do I wash my hands?

The short film 22nd of April by Cesare Maglioni, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5, recreates a situation in the Smara camp that was repeated in many refugee camps during the Covid-19 pandemic and which persists in the most neglected ones. The abundance of messages broadcast by all television channels and social networks on the importance of handwashing, and the flood of how-to videos showing in detail the steps to follow with soap and water to eliminate the virus, were seen on almost every mobile phone in the world.

22nd Of April, short film by Cesare Maglioni, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5 in the micro-documentary category.

A refugee from the Smara camp plays the video while wandering around the camp; he ends up recording the puddle of dirty water with his phone camera after following the instructions that the whole hand-washing process should take 20 seconds, “the time to sing Happy Birthday twice.” The author titles his short film 22nd of April, the date of International Mother Earth Day, so the popular tune becomes a sadly ironic celebration of the UN-instituted holiday, which celebrates its 52nd anniversary this year.

Not everyone in the world can wash their hands, not before, during, or after the pandemic. Beyond the refugee camps, this situation extends to the poorest parts of the world. According to the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP), globally, some 2.27 billion people cannot wash their hands at home adequately.

An obstacle to achieving the SDGs

The drama of access to water, sanitation, and hygiene is endemic and goes along with human pain in every war-related exodus. It is the same story that repeats itself in every war. From the perspective of our aid projects, we have experienced it first-hand in Darfur, Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and now in the terrible war in Ukraine.

According to UNHCR, by the end of 2020, 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced due to persecution, war, violence, human rights violations, or insecurity. The UN agency reminded us that a person was forced to flee their home every three seconds and that 51% of refugees were children.

The war in Ukraine is undoubtedly shattering these figures. When writing this article, 4.5 million people had taken refuge in other countries, and 7.1 million were recorded as internally displaced. Our projects aim to meet the vital needs of refugees, which are multiplying as they accumulate in the camps. We have two projects there: with UNICEF to help the victims who remain inside the country and with World Vision to help those fleeing to Romania and Moldova. All aid is essential to fight against one of the cruelest injustices that the human species commits against itself.