Unrest and violence have marked the regression of Ivorian education since the civil war of 2002. Then, bloody clashes forced more than a million people to migrate internally. After the disputed 2010 elections, violence flared up again, and displacement intensified. Poverty ravaged rural areas, and slums sprawled around the cities. Schools closed for an extended period, and many teachers emigrated to neighboring countries and Europe.

Recycling plastic waste to build schools and sanitation facilities introduces a valuable environmental and educational factor © UNICEF

The educational crisis became permanent in Côte d’Ivoire and was combined with the agricultural emergency in rural areas. There, poverty and lack of opportunities took their toll on young people, especially women.

Slums with no hope of a solution

There are currently almost 30 million inhabitants in Côte d’Ivoire. Nearly five million live in the economic capital, coastal Abidjan, where over half are found in 75 slums. According to the World Bank, since 2018, the percentage of Ivory Coast’s urban population living in slums has stagnated at 53%. Their abandonment is distressing. Some survive on precarious jobs; many do so by scavenging through the garbage in neighboring districts, and any illness can become fatal due to the lack of assistance.

There are currently almost 30 million inhabitants in Côte d’Ivoire. Nearly five million live in the economic capital, coastal Abidjan, where over half are found in 75 slums. © Zenman

Slums are not diminishing, and living conditions are worsening in many of them. In Abidjan, evictions of thousands of residents by the government to build infrastructure for industry and tourism have become a regular practice. After demolishing their precarious dwellings, entire families are evicted with no alternative but to move to another settlement nearby. And the problem is getting worse with no solution in sight.

JMP data corroborate this scourge which is a considerable setback towards SDG 6; they even point to a regression: in 2020, almost 600,000 Ivorian city dwellers were turning to surface water to survive; there were 240,000 more than in 2015. Open defecation also shows concerning figures: in 2020, 1.37 million city dwellers practiced it, some 370,000 more than in 2015.

These data are a symptom of a major socio-economic problem: internal migration processes do not stop, slums are not decreasing, and the situation in many of them is worsening.

An education system in permanent crisis

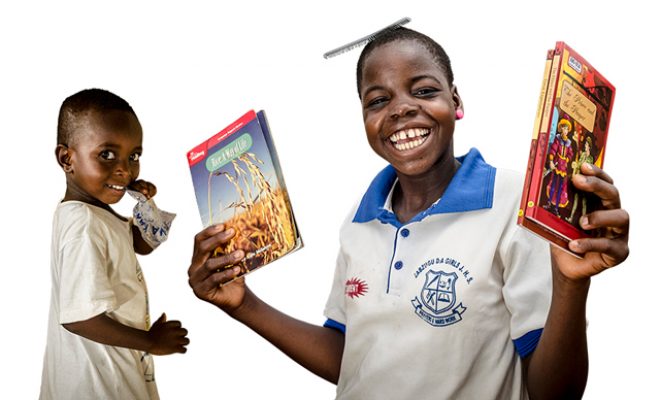

Impoverished rural communities cannot retain the young people who leave home, most of whom have not completed primary school and are not qualified to find employment. Two million children are left out of an education system in a permanent crisis burdened by substantial gender inequalities.

Schools must be built and existing ones improved, and particular emphasis must be placed on ensuring safe water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities, especially for women. Schools must be attractive and stimulating environments for young people and their families. Another of the disastrous consequences of the crisis that began in 2010 is the need for more teachers and their lack of specific qualifications for early childhood education.

There are areas in which, for a population of nearly 200,000 inhabitants, there are only 78 early childhood centers, some 170 teachers, and 146 classrooms with a capacity for at most 4,321 students. In addition, nearly 80% of children have to travel more than 15 km to get to school. Moreover, one out of every five centers is incomplete, only 46% have a drinking water supply point, and half lack adequate sanitation facilities.

Tons of plastic… to be reused

Another problem facing Côte d’Ivoire is plastic pollution, which is damaging health and wreaking havoc on the environment. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the economic capital Abidjan alone produces more than 280 tons of plastic waste daily. Less than 10% is collected for recycling; the remaining 90% is buried in local landfills or dumped unchecked in nature.

A UNICEF initiative is innovatively tackling this problem. The agency has partnered with the Colombian company Conceptos Plásticos, which has set up a factory to make bricks from recycled plastic to build school facilities. The benefits of this initiative are threefold: waste collection is encouraged, cheap raw material is obtained, and communities are made aware of the importance of plastic control and recycling.

In 2021, some 210 classrooms were built thanks to these bricks. UNICEF plans to promote this type of construction to rehabilitate a good part of the most deteriorated school facilities with more than 9,600 tons of plastic the factory will treat annually.

An innovative water and sanitation project

Three of these schools will be operational in 2024 thanks to a project in which we are collaborating in Kabadougou, northwest of the country, where poverty rates reach 61%. The risk of not attending school in this area is 54.6%, primarily girls, one of the country’s highest figures.

In addition to reversing the educational crisis by building classrooms and training teachers, the goal is to radically reduce infant morbidity and mortality caused by inadequate access to water and safe sanitation and hygiene facilities. This situation has prevented the development of a water sanitation culture that would curb malaria, diarrheal diseases, and pneumonia, which are endemic in the region.

The risk of not attending school in the north-west region of Kabadougou is 54.6 per cent, most of them girls, which is among the highest in the country. © UNICEF

Awareness of waste control, achieved through transforming plastic into bricks for the school, is also beneficial in fighting diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, and other illnesses that increase their presence because waste transmits them.

Combining these factors undoubtedly makes it possible to achieve quality early childhood education as a starting point for an effective teaching cycle. Achieving school permanence in rural areas is the first step to stopping the migration that increases the indignity and injustice of the slums.