©UN Photo/Tim McKulka

“Climate change will increase the existing risks and will create new ones for natural and human systems. Risks are unequally spread and, in general, are greater for disadvantaged people and communities in countries with all development levels.” This was one of the forecasts Jean-Pascal Van Ypersele, vice president of IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) communicated in his intervention during World Water Day 2015.

Five years of confirmations

The Belgian climatologist had attended the conference Social Perceptions of Water and Climate organized by the We Are Water Foundation and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in Barcelona. Along with other experts, Van Ypersele summarized the scientific basis and the forecasts of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), whose summary was going to be presented by IPCC at the COP 21 in Paris six months later.

The AR5 has been the roadmap for the mitigation and adaptation to climate change during the last five years, a period of time in which most repercussions present in the document have occurred. This is why this phenomenon is now globally defined as “climate crisis”.

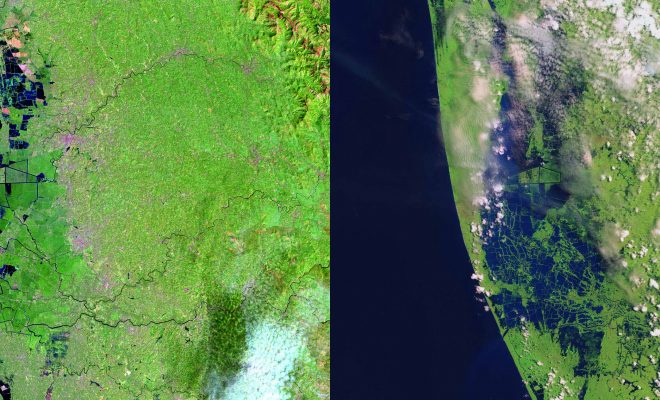

Throughout this time, the UN agencies have stressed the importance of using scientific data to assess and reduce the humanitarian risks of violent meteorological phenomena, one of the most aggressive threats confirmed year after year on the planet. The evolution of these disasters has proven that, beyond any meteorological forecast, it is necessary to move forward in the knowledge of the social and economic context of the exposed areas, as in many occasions it is the poor management of the territory and the inability to respond to the danger what causes more harm than the rain or the wind.

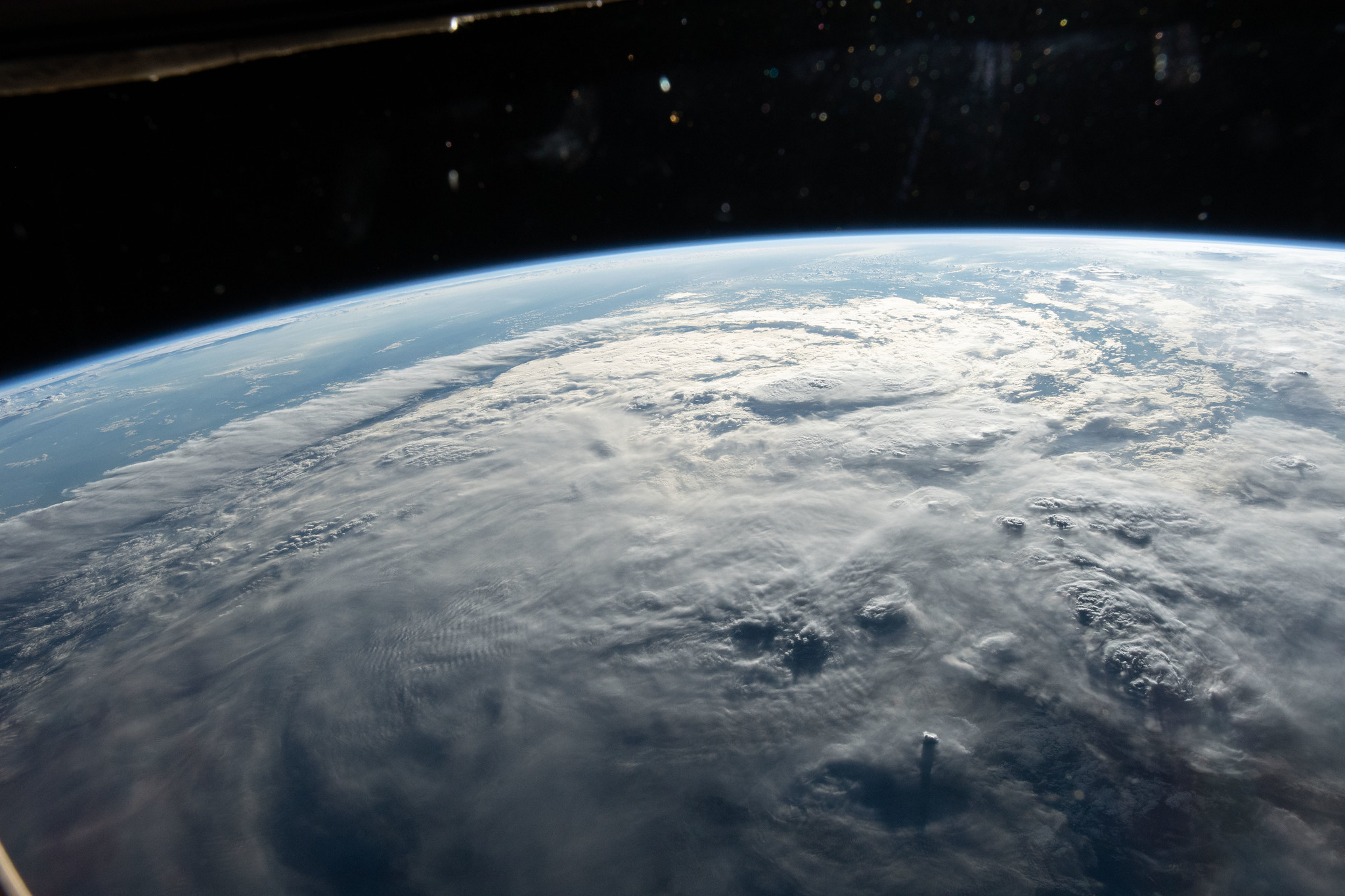

©NASA Johnson/Tropical Cyclone

Understanding the risk factors

The importance of understanding the meaning of risk and the factors that generate it is present in the AR5 and is increasingly relevant in the current work of IPCC for its sixth report, the AR6, which incorporates the vision of the climate crisis from the perspective of social sciences and their importance to improve the adaptation and reduce vulnerability.

The IPCC defines risk as the likelihood that a community will suffer serious disruptions in its normal functioning and human, economic or environmental damage as a result of dangerous physical events. The equation that translates this definition, which is traditionally used in geography as the base for all studies is:

Risk = Hazard x Exposure x Vulnerability

In the case of flood risk, the hazard can be a cyclone, a cold air pool or accelerated melting that causes an excessive hydrological swelling. The data of these last years, especially of the first eight months of 2019, confirm the increase of these dangerous phenomena.

Exposure is defined as the presence of people, homes, buildings, service facilities or any other economic, social or cultural good in areas where violent phenomena may occur. In the case of a floodplain, its inhabitants and their personal or community property are at risk of damage.

© Farhana Asnap / World Bank

Vulnerability is the predisposition of people and their goods to be damaged. For example, a house in the Philippines is exposed to a typhoon, but it is vulnerable if it has been poorly built. The same happens to a faulty or miscalculated sanitation system that pollutes water in a flood: it is a vulnerable installation that makes those people depending on that drinking water vulnerable. Poverty is directly related to vulnerability: deficient facilities, shacks and overcrowded slums are factors that increase vulnerability to flooding.

Risk includes therefore these three factors in a directly proportional relationship: the greater the intensity of the phenomenon and the greater the number of inhabitants and goods exposed, the greater the risk.

Beyond climate change, land management

© McKay Savage / India

Risk management is complex as it depends to a large extent of where in the planet these phenomena occur, of their exposure degree and vulnerability. Poor land management leads, for example to the urbanization of floodplains and the replacement of crops than hinder runoff, such as terraces or fruit trees, with others with less retention power. Historically most cities have been built alongside rivers, many of them in natural flood areas that were occupied with all kinds of goods and inhabitants while they were growing. This occupation has not only increased the exposure and vulnerability, but also the danger of the phenomena as the waterproofing of the soil due to the urban layer increases the violence of the runoff that cause streams and rivers to overflow.

Deforestation, which in many cases has been a consequence of the development of the outskirts of cities, also represents a factor that increases the danger as water drags soil and vegetation with weakened roots that clogs drains and spillways. Many of these infrastructures are deteriorated or obsolete as they were conceived for less voluminous floods.

Many of these problems were highlighted in the floods in southeastern Spain last September.

The danger of this phenomenon broke all records, with rainfall exceeding 450 liters per square meter in 48 hours and more than 140 in two hours, with the subsequent increase in their torrential nature. However, the level of exposure and vulnerability had also increased: in the last decades, agricultural land has been urbanized and many towns have expanded occupying floodplains; many forest areas have increased their aridity and the neglect of river areas has increased, resulting in less clearing of unwanted vegetation. Many traditional farming practices have been discarded in mountain areas close to river basins and streams, such as terrace farming or irrigation systems based on the use of runoff water, practices that contributed to the retention of water, thus reducing flood violence.

These problems can be transferred to many areas in the world that are currently experiencing the increase of floods, such as the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia, the areas close to Sahel in sub-Saharan countries and the most arid regions in India. The climate crisis has greatly affected many of these countries and the forecasts of IPPC continue to be met in the first six months of 2019, as the hydrometeorological natural disasters (cyclones, storms and torrential rains) are being especially aggressive.

Forced displacements to save lives

© UN Photo/Logan Abassi

A reference of the humanitarian repercussion of these phenomena is provided by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), which has been following and analyzing human displacements caused by humanitarian (wars, political or ethnical conflicts) and natural disasters (earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, etc) since 2013.

The IDMC has found that extreme meteorological phenomena cause, on average, 90% of the forced human displacements. In a recent report, the IDMC states that from January to June 2019, more than 5.5 million people were forced to move due to the flooding of their homes or workplaces. Some of the disasters responsible for these displacements have made the headlines; others have not, mostly those in the poorest and more neglected areas of the planet, where vulnerability is very high.

Most of the displacements in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America take place during the rainy seasons, from April to May and from October to November. In the United States and the Caribbean, South and East Asia and the Pacific, the cyclone and typhoon seasons, as well as the monsoon season, usually take place between June and September and in November and December. The IDMC experts point out that, in 2019, the delay of the monsoons in South Asia and the special force of the cyclone season which ends on the 30th November, may greatly increase the figures.

© UN Photo/JC McIlwaine

Many of these displacements, which reduce the exposure and vulnerability of people but not of their goods, which they need to leave behind, have shown a hopeful progress in terms of effectiveness. A noteworthy case was the passage of Cyclone Fani through India and Bangladesh last May, where those affected reached almost 3.5 million. Fani was the most powerful cyclone to hit India in the last 20 years, causing the death of 12 people and the destruction of millions of homes in the poorest areas of the state of Orissa. However, Fani would have caused a humanitarian crisis without the efficient evacuation plan carried out by the government, which was able to drive away in record time more than one million inhabitants thanks to the work of thousands of policemen and volunteers and to the precise instructions given to the population by means of phone messages and public addresses on the streets.

Prevention and land management

©Mans Unides / Erik de Castro

In view of the real increase of violent phenomena, it is essential to apply different and specific prevention measures in each geographical region to reduce exposure and vulnerability. IPCC experts advocate the creation of risk region maps and the development of specific prevention measures for each case. In Europe, the Flood Directive has existed since 2007, which involved a new risk management, with the identification of river and coastal sections that could be flooded, the drawing up of hazard and risk maps, and the preparation of flood risk management plans (FRMPs).

Adequate risk management in the face of extreme meteorological phenomena should increase the knowledge of climate date and real-time meteorological forecasts, but it should also include adequate land management to reduce exposure and vulnerability. There needs to be international consensus so that, above all, the most vulnerable communities become aware of the significance of the risk in which they live in order to foster their capacity for self-protection and put pressure on the political power to ensure their safety by reducing their exposure and vulnerability. The climate crisis poses a challenge that is proving to be pressing.

© United Nations Photo