Humanity has never known a period in which famine was not causing pain and death somewhere on Earth. Famines have traditionally been one of the most prominent indicators of poverty, neglect, injustice, and inequality. Droughts, wars, inflation, and epidemics cause hunger and show us the extreme vulnerability of food security. Lately, we are becoming aware of a new insecurity factor: the food system is unsustainable and increases climate change.

There has always been a very close link between climate and hunger. But this link was not studied in depth until the most powerful economies realized that droughts and lack of access to water were essential factors in geopolitical imbalance. In 1974, the United Nations General Assembly convened the World Food Conference in Rome. The most significant economies and leading political observers warned that climate variations should be closely monitored, and efforts to prevent them should be redoubled. At the time, there was still no talk of “climate change.” However, scientific reports announcing it and warning of its destabilizing effect were already accumulating in the offices of those in power.

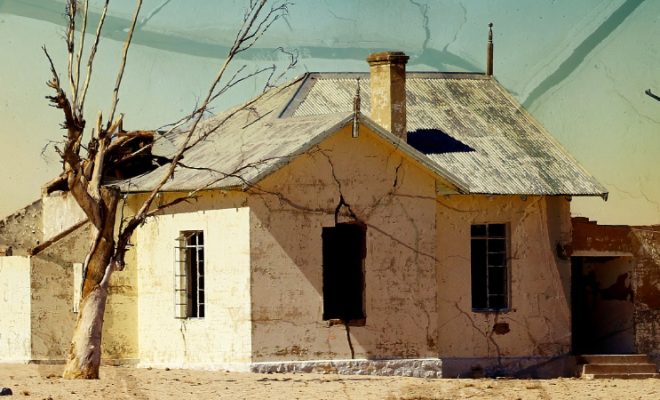

In the 1980s, famines in Africa shocked developed countries and brought the harsh reality of droughts closer to society. Since then, as climate change manifested itself, the evidence that global warming was a factor in food insecurity became indisputable. The always complicated and thorny management of agricultural land and the water use for irrigation were at the center of criticism and ideas; it is not for nothing that agriculture and livestock are the sectors that consume the most water (between 70 and 90%, depending on the country).

Making the food system sustainable is one of the major challenges of this decade. © Annie Spratt-unsplash

Climate and food, it makes no difference

In 2019, just before the coronavirus pandemic, two scientific reports went headlong into criticizing the global food system from the perspective of climate doom and gloom. The first was the EAT-Lancet Commission Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems report. This study added some controversy by asking a question that circled the globe and to which we still do not have a satisfactory answer: “What” and “how” should the Earth’s nearly 8 billion people eat to ensure the sustainability of the global food system?”

Droughts, wars, inflation, and epidemics cause hunger and show us the extreme vulnerability of food security. © UNDP

The second report was released two months later. The IPCC turned the climate issue on its head by publishing the Special Report on Climate Change and Land,an in-depth study by 107 experts from 52 countries. The report was a milestone as it was the first time climatologists thoroughly studied food security, highlighting the enormous differences in food consumption and production systems worldwide.

The determining factor of the importance of the food system in global sustainability is the water footprint, the water used in the production of goods and services. Almost 92% of the planetary water footprint belongs to food production, and food of animal origin is among the most water-intensive. You can see for yourself if you check our mobile app, We Eat Water.

The water footprint of economic activity is closely related to the carbon footprint, and both have an impact on the ecological footprint. Now, more than ever, it is clear that the three footprints must be the instruments for developing a joint strategy.

It is essential to make a common front so that water saving technologies are implemented and reach the most abandoned communities. In the image, two women do their best to dig another piece of land from which they foresee a good harvest, although the soil tends to dry out. Mozambique © Leopoldino Jeronimo / Kepa

Three simultaneous strategies

This link between food and climate raises social and political controversy, but it is unavoidable in the race to achieve the SDGs. Last June, the United Nations hosted Stockholm+50, a meeting between governments, private companies, and civil society representatives, especially young people, to accelerate environmental action towards 2030.

The event’s title refers to the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in the same Swedish capital in 1972. The spirit of the meeting showed some pessimistic aspects: we have made little progress in safeguarding biodiversity, pollution control, and food in half a century. In fact, despite evident improvements, the unfinished business remains the same, and new negative factors have been added, such as climate change and the lack of control of the food system, which was one of the most important topics of the discussions.

To this effect, the experts’ conclusions were clear: the food system is the main contributor to our exceeding the limits of nature and the cause of a large part of greenhouse gas emissions and overexploitation of water. Its revision was raised as one of the most urgent needs for the international community. There was no lack of proposals, and the good news was the alignment of all parties in defining strategies.

The first refers to the review of the world agricultural model. It is essential to make a common front so that water-saving technologies are implemented and reach the most neglected communities while reducing the use of chemical products, such as fertilizers and pesticides, and adopting techniques based on diversified and regenerative crops. Appropriate governance measures are needed here: a global reference framework is required to improve agricultural land management in line with the availability of water and the climatic conditions of each region. There is also an urgent need to design incentives for investment in sustainable techniques and ecological research of the territory.

Another urgent strategy is the investment in climate and meteorological research. It is essential to forecast with maximum accuracy the dreaded concurrent droughts and heat waves, mainly if these can occur together with droughts. Investment in local forecasting systems is essential to optimize rainwater harvesting techniques and save irrigation water.

FAO warns that the much-condemned livestock is economically crucial for about 60% of rural households in developing countries. © Bindaas Madhavi

The dietary controversy

The revision of dietary habits was also present in Stockholm. In the Special Report on Climate Change and Land, the IPCC recommends making decisive progress in reducing meat consumption, encouraging the consumption of seasonal and local vegetables, and reducing the appalling food waste. The adoption of an “international dietary front” is complicated because, in addition to the pressures of food markets, it is very complex to consider together the diet of those who have the privilege of eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day with that of the approximately 1.7 billion people who subsist on low-quality starches and have minimal access to milk, meat, eggs, and fish. FAO warns that the much-condemned livestock is economically crucial for about 60% of rural households in developing countries.

There is no turning back now; up to this point, the energy and transport sectors had been the main scenarios in which mitigation and adaptation solutions to the climate crisis were drawn and planned. Now the food system is emerging as one of the significant challenges for the remainder of the decade toward the SDGs.