When the war between Israel and Hezbollah broke out in 2006, water stress was already endemic in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. The arrival of refugees from the south worsened the situation, and many of the already deteriorating water supply and sanitation facilities collapsed. The situation was particularly critical in schools hosting children. Although the government made efforts, water resources dwindled due to severe droughts, and the region entered a phase of scarcity. Water supply cuts became daily, and in many communities, water was rationed through tanker trucks.

In 2011, the outbreak of the Syrian civil war triggered a new wave of migration. According to UNHCR, by 2018, nearly a million Syrian refugees had entered Lebanon, with more than 350,000 settling in the Bekaa Valley. Additionally, the lack of maintenance of sanitation facilities contaminated many water bodies. The situation became critical again: only 36% of the population had access to safe drinking water services, and water supply cuts reappeared.

That same year, we started an aid project that allowed us to experience firsthand the reality of water scarcity among the population, especially in the schools of the Bekaa Valley. In addition to constructing water and sanitation systems, benefiting more than 7,000 Lebanese and Syrians, the project reaffirmed the importance of working with Water Committees to promote social cohesion, essential for adequately managing water stress.

The climate crisis, war conflicts, and pollution threaten to worsen the situation in countries that need it most. © Muhammad Amdad Hossain

From Water Stress to Scarcity

The case of the Bekaa Valley is a good example of a situation that repeats itself in many regions of the world. Water stress (when water demand exceeds availability) is the precursor to scarcity (when there is simply no water available for consumption). This transition from stress to scarcity can be triggered by a migration wave, recurring drought, pollution, or armed conflict; often, it is a combination of all these factors, as seen in Lebanon.

Two years ago, the UN acknowledged that we would not achieve SDG 6 by 2030. Its latest report, published this summer, shows figures that, despite some improvements, remain far from predicting universal access to safe drinking water. According to its projections, at the current pace of progress, 2 billion people will live without safe water management by 2030, and water stress will continue to be a growing problem: in 2021, it reached a global average of 18.6%, with Central and South Asia showing alarming levels and North Africa in a critical situation.

What is most concerning is that since 2015, global water stress has increased by 3%, with particularly alarming increases in North Africa and the Middle East, where it has risen by 12%. As for scarcity, in 2022, approximately half of the world’s population experienced water shortages for at least part of the year.

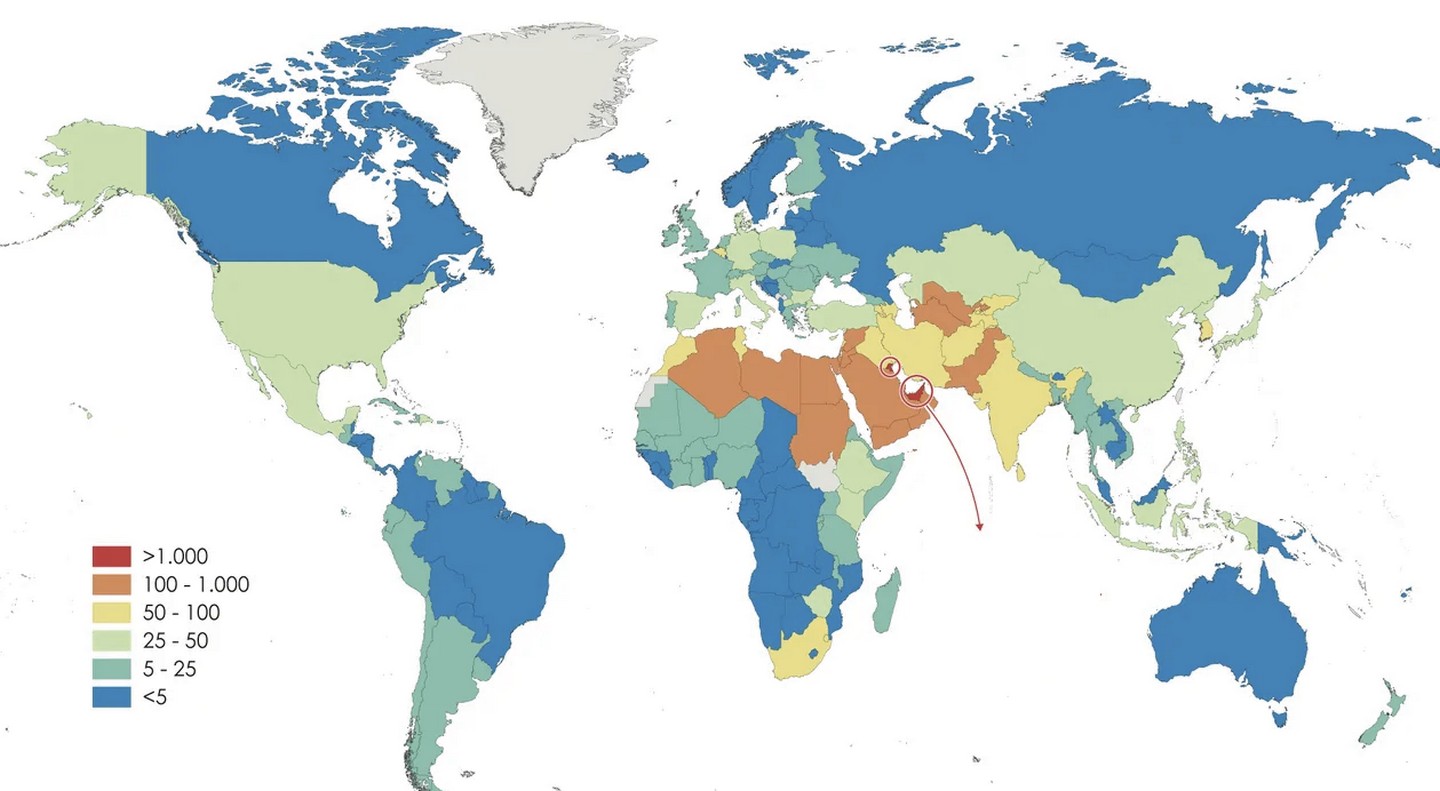

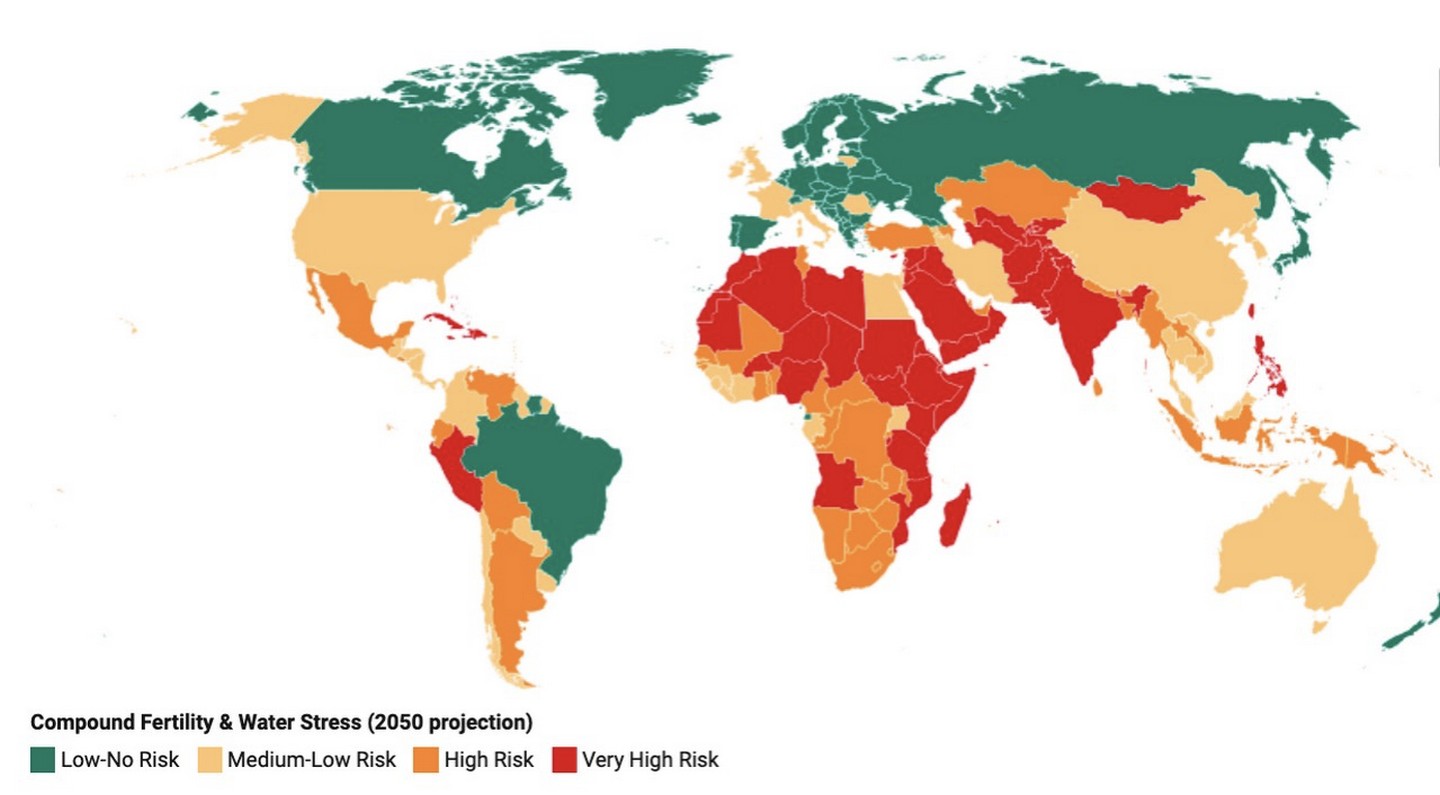

The following maps show how freshwater extraction is distributed worldwide based on renewable resources—water stress levels—and the relationship between stress and population growth.

How Will We Reach 2030

The UN acknowledges that we are far from achieving the 17 SDGs. Last year, it already warned about the urgent need for acceleration to achieve at least a significant reduction in the most critical indicators. The challenges in advancing SDG 6 are also reflected in the remaining 16 goals.

In its report, the UN highlights the persistent effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the escalation of armed conflicts, geopolitical tensions, and the growing climate crisis as the main obstacles. Although the pandemic has largely been overcome, international conflicts and climate change remain sources of uncertainty. Displacement flows, both climate-related and those fleeing violence, represent a humanitarian drama and disrupt access to water, sanitation, and hygiene in host regions. These situations mainly occur in the most affected areas, as shown by Maps 1 and 2, highlighting the severity of their consequences.

Freshwater extraction as a percentage of available renewable water resources (2020). The cases of Kuwait and the UAE (in red) are significant, consuming 38 and 16 times the volume of renewable water, respectively, thanks to massive seawater desalination. Datawrapper / World Bank.

Projected population growth with water availability by 2050. One-quarter of the world’s population, about 2 billion people, currently live in water stress conditions, and developing regions will experience the most water stress. Datawrapper / World Bank.

In our project in the Bekaa Valley, it became clear how important it is to plan for the reception of refugees in areas where water stress is endemic. However, planning is often complicated, as we have seen in our projects assisting more than 1.7 million refugees in five countries, in addition to Lebanon; 184,000 of them were in refugee camps in Rwanda, Ukraine, Romania, Moldova, and Chad. Except for the war in Ukraine, conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan rarely make headlines or become trending topics on social media; they are “forgotten” conflicts by much of the global community. Who considers them in future forecasts?

Controlling water stress and ending scarcity is essential to achieving food security and reducing poverty. Understanding the causes of scarcity and mapping the most needy areas is the first step in managing them effectively. There is still much work to be done, but no one can say they don’t know what needs to be done to ensure that water meets everyone’s needs.

Controlling water stress and ending scarcity is essential to achieving food security and reducing poverty. © Muhammad Amdad Hossain