Last November, while at COP27, the powers discussed the damage caused by climate change and how to reach a fair agreement to help the countries suffering the most. More than seven million people were at risk of extreme famine in Somalia. After five failed rainy seasons, the country, one of the lowest carbon emitters, was on the brink of a humanitarian abyss, with half a million children suffering from months of malnutrition.

The situation has not improved in the last two months. Intermón Oxfam claims that one person dies of hunger every 36 seconds in the Horn of Africa, the geographical area of which Somalia occupies the far east. Most nomadic herders have lost almost all their livestock in the country’s arid north. Camels, sheep, and goats, of varieties that over the millennia have become highly drought-resistant, have this time been unable to cope with the prolonged lack of water and the drastic decrease in the pastures.

At the eastern tip of the Horn of Africa, Somalia is struggling with an unprecedented humanitarian crisis © Stuart Isaac Harrier -unsplash

UNHCR estimated in December that by 2022 the number of displaced Somalis would be around 857,000. Chances are that it will now be even more. In a country where more than two million people drink from surface water (ponds and rivers), groups of families walk for days to reach the refugee camps in search of help. In cities, such as Baidoa, in the wetter and greener south, up to 500 camps are set up where NGOs shelter them as best they can.

Much of the international aid does not reach its destination. Terrorist groups of Al Shabab, a jihadist movement affiliated with Al Qaeda, steal food, water, and medicines while a weak government with too many open fronts remains powerless. Corruption is also an aggravating factor: according to Transparency International, in 2009, Somalia was the most corrupt country in the world. According to UN international observers, the situation has improved, but this social scourge continues to cause illness and death to those most in need. To make a disastrous year even worse, the invasion of Ukraine has also pushed up world food and fuel prices, making transport more expensive and affecting aid deliveries.

Most nomadic herders have lost almost all their livestock in the country’s arid north.. © UNICEF / Mulugeta Ayene

A recurrent tragedy in a millenary semidesert

Humanitarian crises are recurrent in Somalia, as are unfulfilled promises. In 2011, after 250,000 people died of malnutrition, the international reaction was powerful, and world leaders promised in the media that nothing like this would ever happen again. But it happened again in 2017 when another drought left behind over 260,000 dead, more than half of them children.

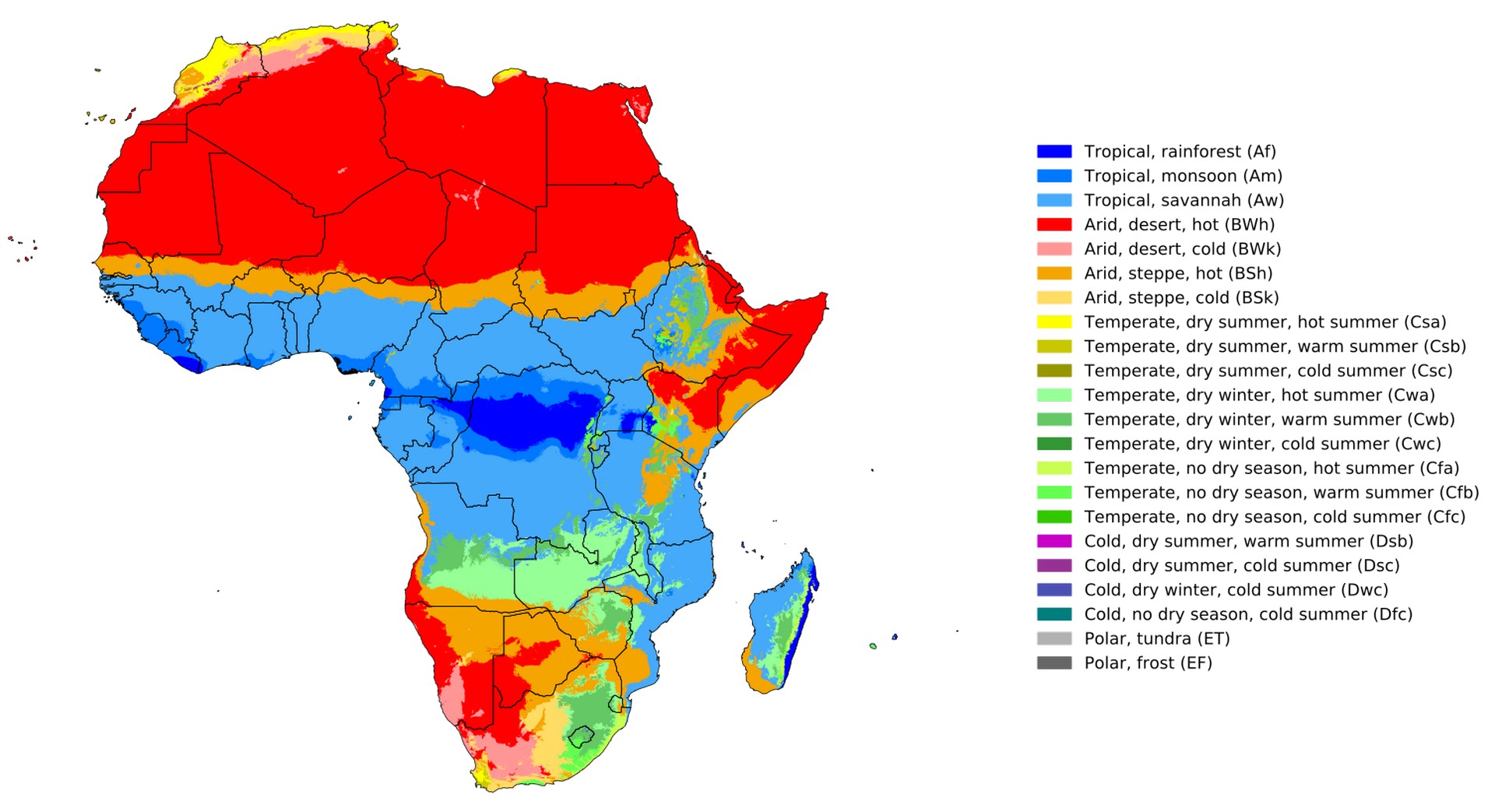

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned as early as 2008, when it published its report Climate Change and Water, that declining rainfall would increase water stress in the Horn of Africa. In this area, wet winds from the Atlantic have a hard time bringing rain (see map). In Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia, aridity is millennia old, but the short- and medium-term outlook is even drier: a total desert is looming.

Map depicting Africa’s climate according to soil moisture. From the wettest tropical forests, in blue, to the deserts, in red. It can be seen how the rains, of Atlantic origin, do not reach the Horn of Africa in the far east, which is also far from the humid Indian monsoons © Köppen-Geiger / Beck, H.E., Zimmermann, N. E., McVicar, T. R., Vergopolan, N., Berg, A., & Wood, E. F.

Since ancient times, the semi-desert north has forced its inhabitants to develop nomadic subsistence livestock farming, in contrast to the more humid south. There, agriculture prevails, accounting for about 65% of GDP and employing most of the working population. But significant variations in seasonal rainfall also threaten sorghum, sugarcane, corn, and banana crops, causing uneven harvests that add to economic uncertainty.

As in Somalia and the rest of the countries in the Horn of Africa, violence, corruption, and social imbalance lie hidden in the oblivion of international public opinion. © Ismail Salad Osman-unsplash

Other crises under drought

It is not only the climate crisis that is the cause of the famine. Since its birth as a nation in 1960, ethnic clashes, various episodes of civil war, and armed conflicts with neighboring countries have become endemic in Somalia. This represents the dire consequences of the combination of drought and war.

The drying land often reveals profound humanitarian dramas to the world. As in Somalia and the rest of the countries in the Horn of Africa, violence, corruption, and social imbalance lie hidden in the oblivion of international public opinion. After the desertification of the Sahel, the floods in South Sudan, the landslides in Sierra Leone, the salinization of the deltas in Bangladesh and Vietnam, and many other natural disasters, a substratum of poverty and neglect appears that impacts the world and forces us to reflect on how to move towards the SDGs effectively.

The agreement on “loss and damage,” which the Parties meeting in Sharm El Sheikh agreed to finalize in the short term, must take these circumstances into account and open the eyes of the world to the complexity of the problems suffered by the countries that have contributed least to global warming and which suffer most from its consequences. Money is not enough; what is needed is international political solidarity that does not hide the social drama in which the poorest economies are struggling.