After 11 years of war, the situation in Syria is far from being resolved. The war continues to cause the world’s largest refugee crisis, with over six million people internally displaced and more than five million living in neighboring countries as refugees, most of them in extreme poverty and lacking water and sanitation. In our Bekaa Valley project, you can see the pressure this flood of displaced people puts on neighboring countries, such as Lebanon, where water stress is also endemic.

The war has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives; more than 12 million go hungry daily, and 80% of the population lives below the poverty line. According to UNICEF, some 6.5 million Syrian children require assistance, while nearly 5.8 million depend on aid in neighboring countries. This is the highest figure ever recorded since the beginning of the conflict.

The water access crisis, inherent in all wars, has only worsened and, in recent years, has become a humanitarian emergency that climate change threatens to end in a devastating way. The waters of the Euphrates, Syria’s main river, are dwindling in flow and quality, and are a key factor.

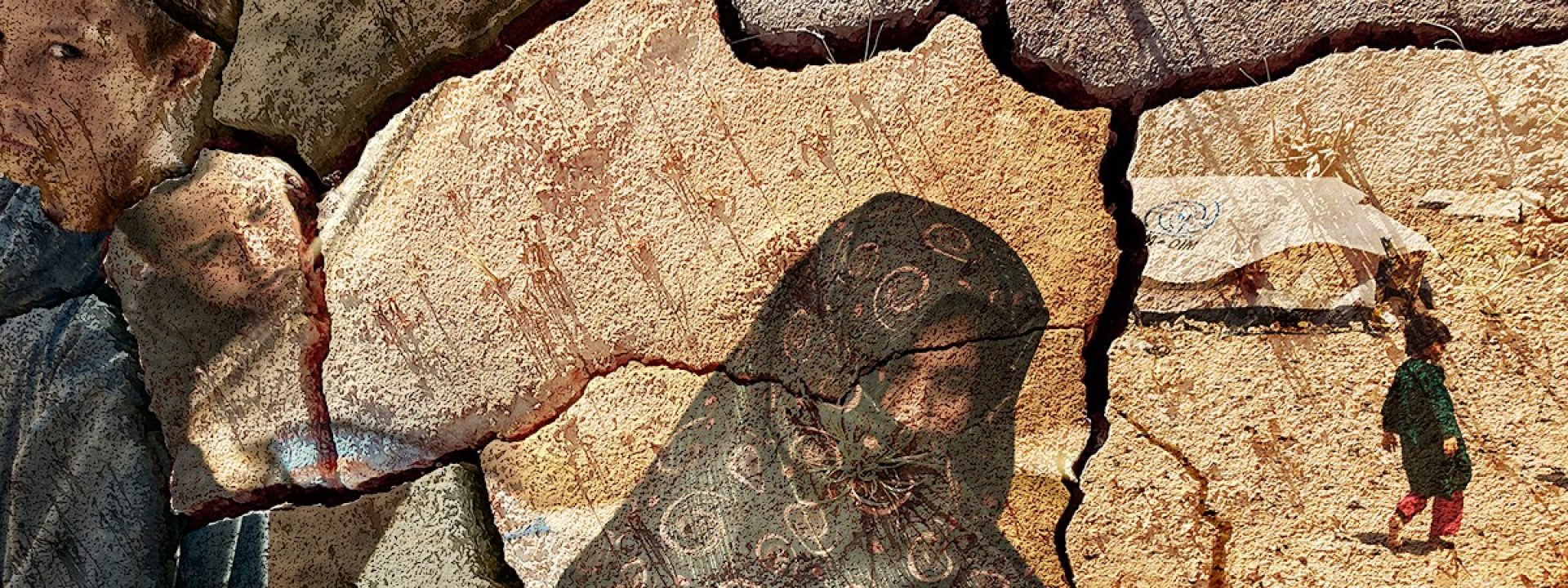

In recent years, severe droughts and heat waves have triggered a water crisis in the basin of the Euphrates, Syria’s main river. © Dr. Colleen Morgan

The most complicated water geopolitics

The Euphrates rises in Turkey, flows through the Anatolian mountains, crosses northeastern Syria and then Iraq, running parallel to the Tigris and then joining it to form the Shatt al-Arab, before flowing into the Persian Gulf.

The Sumerian civilization, considered the first in the world, flourished in the waters of the Euphrates between 3,000 and 2,350 BC. Even then, the flow along its 2,780 km was very unstable in relation to the size of its basin. The river flows through arid and semi-desert areas where the first water collection facilities, aqueducts, and irrigation systems in history were built, some of which are still in use today.

As in ancient times, the unique geopolitical situation of the river has been the scene of water conflicts that have increased during the last decades, when the water demand has increased.

In Syria, the war has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives; more than 12 million go hungry daily, and 80% of the population lives below the poverty line. © Aleppo_VOA

Currently, in Turkey, the massive construction of hydraulic dams leaves an average flow of 830 m³/sec when the river enters Syria, which ranges from 300 m³/sec in the dry season to 5,200 m³/sec at its peak flows that generally cause floods. But over the past five years, the flow of the Euphrates has only decreased. In the low water of 2021, the area recorded the worst drought since 1953, and one of the most feared situations occurred: Turkey retained even more water in the large reservoirs of its territory. This drop in flow, coupled with the heat wave this past summer, triggered one of the most severe water crises in Syria, which has reached Iraq downstream.

In the northeast of the country, 70-80% of the territory has been left without safe access to water. This summer, 40% of agricultural areas have had no irrigation water, and many hydroelectric dams have had to stop operating.

Water, a war weapon

All this has fallen on a country that has suffered the worst consequences of the use of water as a war weapon. It is a wicked strategy that is repeated in almost every armed confrontation. We saw it in the Balkan war, and we are seeing it in Ukraine, Yemen, Afghanistan, Sudan, Congo… In modern wars, the “front,” understood as a combat zone, is usually diluted between population centers, always reaching the civilian population. The water supply becomes an element to control and wear out the population.

According to UNICEF, in recent months, five million people in Syria have suffered the consequences of prolonged water supply cuts, many of them perversely planned. In some cities, such as Aleppo, some neighborhoods had no water for 17 days.

If supply points are arranged with water tankers, the queues also become deadly zones where crossfire or deliberate snipers spread terror among those who come with jerry cans to get water; most are women and children.

NGOs working in the area report many cases of surface water consumption, such as puddles caused by burst pipes or digging of makeshift wells in the streets to reach groundwater.

In addition to the intentional destruction, the bombings have caused severe damage to pipelines in the cities, and municipal technicians are often unable to undertake the necessary repairs. The situation is worsened by frequent power cuts, which paralyze water pumping. Some areas only have one hour of electricity a day, and outages of up to four days have been recorded.

On the other hand, water prices in places like Aleppo have increased by 3,000% this summer, making it impossible for the vast majority of the population to buy it.

In modern wars, the “front,” understood as a combat zone, is usually diluted between population centers, always reaching the civilian population. © Spoilt.exile/Ukraine

Diseases in addition to hunger

UNICEF reports that since the beginning of this year through the summer, 105,886 cases of acute diarrhea have been reported among children in Syria. Hepatitis A is also on the rise, with a record 1,700 cases detected in just one week during February. There have also been outbreaks of cutaneous leishmaniasis, a skin-ulcer disease that affects the world’s poorest populations and is associated with malnutrition, population displacement, and poor water.

The war also affects the sanitation facilities that treat wastewater discharged into the Euphrates. In Deir-Ez-Zour, in the east of the country, 1,144 cases of typhoid were detected in June, and the risk of disease outbreaks is particularly high.

In Syria, the war continues to cause the world’s largest refugee crisis. According to UNICEF, some 6.5 million Syrian children require assistance, while nearly 5.8 million depend on aid in neighboring countries. © UNHCR/ACNUR Américas

What international reaction?

Given the grave humanitarian situation, the UN issued a statement last May urging the Security Council to guarantee the entry of aid into the country. Furthermore, it requested funding for the drilling of wells as alternative sources of water, the support of local production, and the purchase of supplies for the purification and treatment of water from the Euphrates and its tributaries.

There are three clear objectives:

- Stop water cut-offs and all actions that disrupt its public supply in accordance with International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

- Stop all attacks against water facilities, treatment plants, pipelines, and infrastructure.

- Protect the safety of personnel repairing supply facilities.

- Refrain from attacking civilians at collection points.

It is a difficult challenge to address in such a confusing conflict with many international implications. But a world that aims to “promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies” in its SDG 16 cannot falter in humanitarian crises.