A new project in Sierra Leone shows us the importance of ensuring water and sanitation in schools to reverse the impoverishment of neglected rural areas.

Decades of war, the uncontrolled exploitation of its natural resources, and the successive ineffective governments in eradicating the illegal trade of its enormous mineral wealth (diamonds, bauxite, platinum, rutile, and iron) are the reason why Sierra Leone is the seventh poorest country in the world. The small western sub-Saharan country is also one of the countries with the highest levels of inequality in income distribution.

Access to water is an exasperating contradiction: with more than 26,000 m3 of water per capita per year, the country is among the richest in water resources worldwide, but it is one of the worst in terms of access. In 2020, according to the JMP, more than one million inhabitants in rural areas of the country (23% of the population) obtained their water from an unimproved source, and some 860,000 had surface water (rivers, lakes, and ponds) as their only possibility of supply.

The lack of sanitation is another scourge that hinders development and contributes to the country’s social imbalance. More than 1.2 million inhabitants of rural towns and villages defecate in the open, and almost 1.8 million have nowhere to wash their hands.

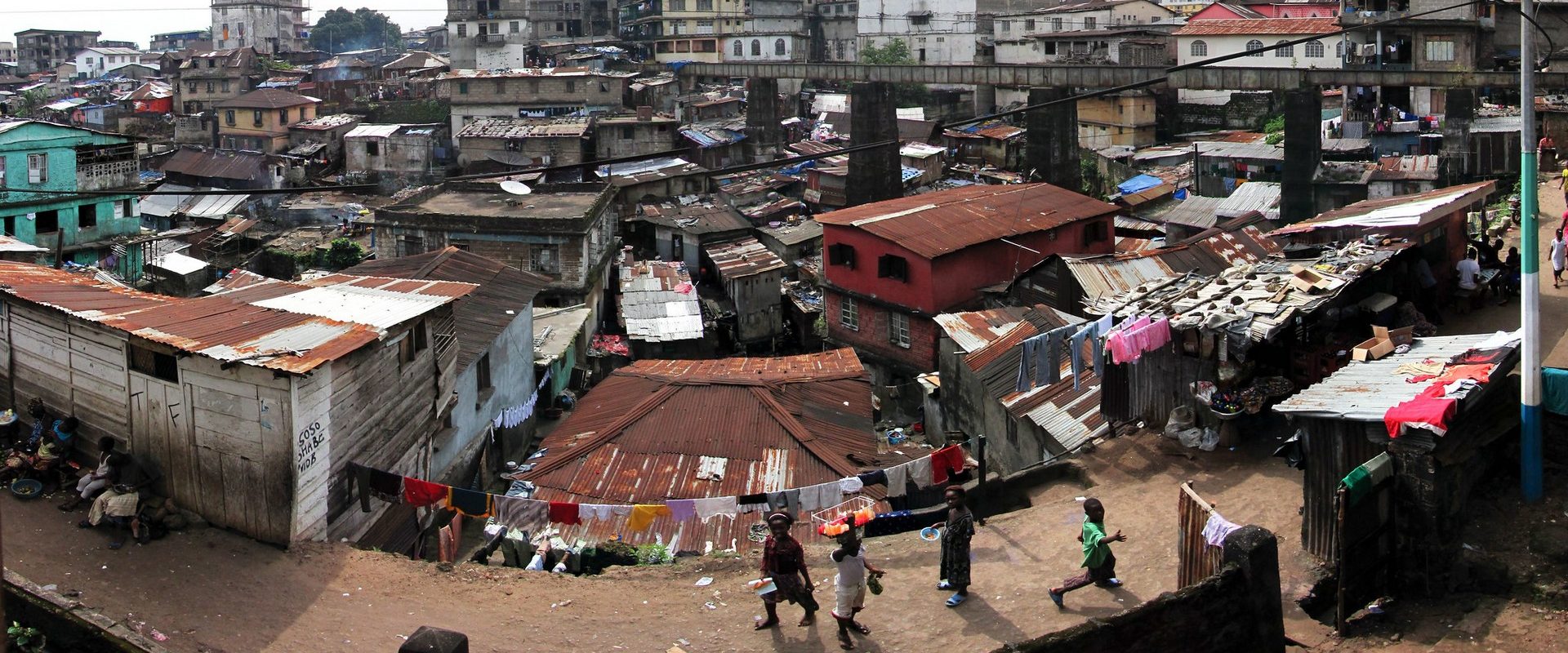

In this context, the endemic poverty peasants suffer generates constant migratory pressure toward the cities, and the slums continue to grow. This drama, characteristic of most large cities of the poor world, is particularly evident in the capital Freetown. In slums, such as Mount Aureol, thousands of people live in indignity, like Kadija A. Bangura, a seven-year-old girl who has to cross a filthy path every day to fetch water from a well, then carries the jerrycan on her head and returns to school on time, which she often fails to do. The micro-documentary Far Away, one of the finalists of the We Art Water Film Festival 4, shows the daily routine of millions of girls who, like Kadija, have the task of fetching water for their families.

Far Away by Robino (Sierra Leone), finalist in the micro-documentary category at the We Art Water Film Festival 4.

In these slums, 85% of the buildings are unregistered shacks, built by deforesting protected areas and lacking water, sanitation, and electricity services. Moreover, they are often erected in areas exposed to runoff from the frequent storms in the country. In the Regent district of Freetown, everyone remembers August 14, 2017, when after three days of torrential rains, floods and landslides took the lives of more than 1,000 people and left more than 3,000 of the shanty dwellers under the Sugar Loaf mountainside homeless. The disaster revealed to the world the degradation of the city’s slums.

More than five years have passed and little has improved, as every rainy season brings news of landslide deaths in the most degraded neighborhoods of Sierra Leone’s cities.

In the slums of Freetown, 85% of the buildings are unregistered shacks, built by deforesting protected areas and lacking water, sanitation, and electricity services. © Babak Fakhamzadeh

The neglect of rural schools

The degradation of education is a factor that feeds into rural poverty and swells slums; it is part of a vicious cycle that must be broken. The lack of water and sanitation in rural schools in Sierra Leone is dramatic. Even the JMP has difficulties obtaining data, which is symptomatic of the administrative neglect in which its inhabitants live. Nevertheless, it is estimated that more than 50% of the schools nationwide do not have a drinking water service, and almost 1.7 million schoolchildren cannot drink or wash their hands in their schools.

Regarding sanitation and hygiene, the figures logically run parallel to the lack of water: more than 36% of schools have no latrine facilities at all, which means that around 1.2 million schoolchildren have to go outside to relieve themselves in the open air.

The JMP statistics do not specify whether the more than one million schoolchildren who have limited sanitation facilities in their centers have them safely separated by gender; however, reports from NGOs working in the country claim that the vast majority of girls and adolescent girls have no privacy in the use of latrines. In this context, it is not surprising that the country also has one of the highest school dropout rates in the world.

In the southern and eastern regions of the country, in the districts of Bo, Pujehun, Bonthe, and Kono, we are collaborating with World Vision to ensure access to water, sanitation, and hygiene in 10 schools.

10 schools, 10 sources for the future

In the southern and eastern regions of the country, in the districts of Bo, Pujehun, Bonthe, and Kono, we are collaborating with World Vision on a project to ensure access to water, sanitation, and hygiene in 10 schools. As a result, in addition to more than 6,000 schoolchildren and teachers, some 36,000 people in their communities, mainly their families, will benefit.

In these districts, dysentery, cholera, and other diseases due to poor water and hygiene are endemic among children. The situation worsened following the Covid-19 pandemic, making the urgency of providing adequate facilities for schools even more evident. Girls and adolescent girls are always the most affected, as the lack of hygiene is compounded by the impossibility of using private and sanitary facilities during menstruation. The consequences are an increase in school absenteeism and, in many cases, the girls dropping out of school, which deepens the gender inequality gap, another scourge that hinders the social and economic development of their communities.

In this project, we emphasize the importance of ensuring sustainability by creating health clubs in each center, the purpose of which is to transfer to the students themselves the responsibility of caring for the facilities and waste management. These clubs are the basis for training young people to practice hygiene and pass on the knowledge acquired to their families. This training of pupils has been a successful experience in the 23 projects in 12 countries in which we have been active directly in schools: more than 200,000 pupils and their teachers have access to total hygiene in their schools and have become educational agents in their communities.

Ensuring education in rural areas is the basis for providing future prospects for the community. If young people are trained, they will be able to reverse their impoverishment and move towards territorial rebalancing, essential conditions to stop the ill-fated exodus to the cities. Without water and sanitation, it is impossible to build an education system capable of meeting this challenge which, in addition to being economic, is ethical for any culture on the planet.