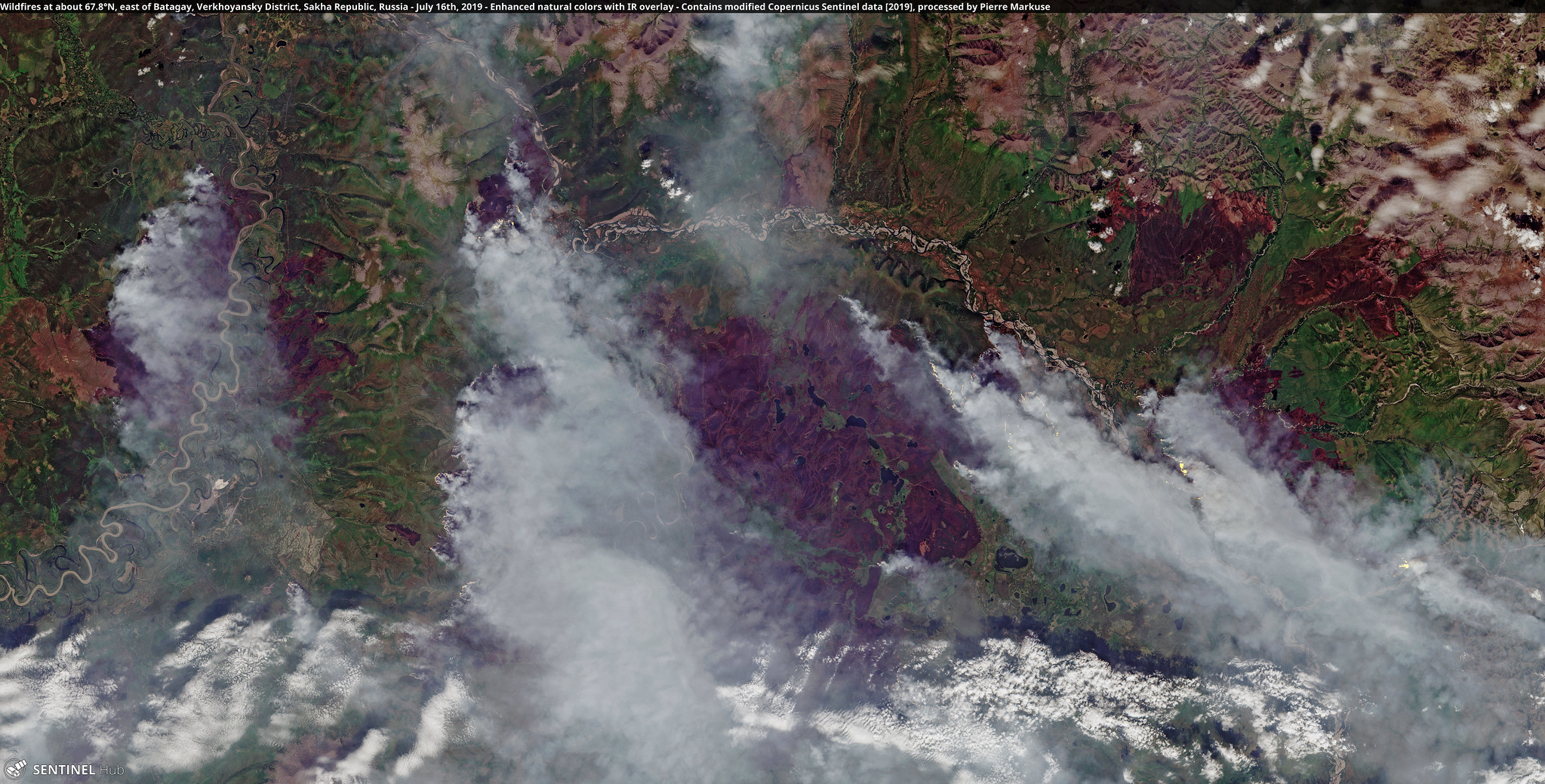

Fires in the Russian Arctic© Copernicus Sentinel data [2019], processed by Pierre Markuse

Permafrost was an unfamiliar term until the heat wave and forest fires of the last two summers in large areas close to the Arctic Circle, such as Alaska, Scandinavia and Russia, made the headlines. The alarms raised by the fires led to the dissemination of recent scientific studies that prove that permafrost, the frozen subsoil of the northern areas and in the highest mountains of the planet, had started melting rather rapidly due to rising atmospheric temperatures.

Geologists and climatologists warn that, similar to the ice of the Arctic ice cap and the alpine glaciers, the planet is losing a key element in the environmental balance and in the fight against the increase of greenhouse gases.

During the last COP25 held in Madrid, one of the work documents has been the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate presented last summer by IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). The document explains that the permafrost temperatures have risen to record levels since 1980 and warns that this Arctic layer contains between 1,460 and 1,600 gigatons (billion tons) of organic carbon, almost twice the carbon we currently find in the atmosphere. If its loss is completed, then global warming might accelerate to unpredictable levels.

Tens of thousands of years of permanent freezing

Arctic lands© Joanna Kosinska on Unsplash

The etymology of the term “permafrost” comes from the English language, meaning permanent frost. It is a layer that underlies the “active” layer of the soil where life develops and that stays frozen all year round, even in summer. It is made up of different amounts of inorganic material (rocks and sand), mixed with organic compounds and water. Frozen water appears in very variable quantities and is a key element in the consistency and durability of the layer over time. Generally, permafrost has a geological age of more than 15,000 years.

Carbon stored in the permafrost is found in organic matter, mainly made up of dead plants accumulated throughout millennia and preserved by the cold. When thawed, this vegetal mass decomposes and creates a mud that releases carbon dioxide (CO2) andmethane (CH4). The latter is the most harmful gas for global warming: research by the State University of Florida estimates that, over 100 years, a ton of methane has a 33 times greater warming effect than one ton of carbon dioxide and its release into the atmosphere would be a real climate bomb.

The expanse of permafrost is enormous: between 20% and 24% of the earth’s surface, mainly in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Scandinavia and Russia, has a layer of permafrost. This frozen layer reaches a depth of over 400 meters although in some areas of Siberia it can be 1,500 meters deep. Above it, the active layer, which is usually between half a meter and four meters thick, is home to important plant life, such as the taiga, the northern forest and the tundra, the treeless vegetation area located north of the taiga.

Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, Canada. © Boris Radosavljevic

The release of carbon has already started

For decades, climatologists have studied Arctic ice, which is a valuable source of information due to its geological age. In fact, most of the data on the accumulation of greenhouse effect gases used in scientific projections comes from the analysis of polar ice and the frozen subsoil. To do this, researchers drill inside it and take a series of samples at different depths. The study of this data helps to evaluate the temperature of the planet in the last centuries and provides valuable information on the existing relationship between climate and soil.

And there is a direct and important relationship. A global increase of the temperature in around 2ºC above pre-industrial levels would mean the loss of 40% of the surface covered by permafrost. This is a worrying situation, as these values refer to the planet’s average and according to data of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC in Spanish), while the planetary average is now approximately 1ºC above the temperature in the 1970s, the Arctic is 3ºC above it.

Scientists point out that the thawing of permafrost has already started. According to the Alfred Wegener Institute, 50 million tons of carbon dioxide have been released into the atmosphere in Alaska alone this year, the equivalent to all the fires in the Arctic last year.

The Doomsday Vault is in danger

These are no suppositions. Two years ago, officials at the so-called “Doomsday Vault”, which houses the World Seed Bank in Svalbard, on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, confirmed water leaks from melting permafrost. This warehouse, an initiative of the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, holds 930,000 seeds of more than 4,000 plant species.

The aim was to be able to regenerate plant life after a hypothetical planetary cataclysm – hence the “Doomsday Vault”. To do this, a cavity was designed inside a rocky massif 130 meters above sea level to be safe from earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, nuclear explosions and rising sea levels. 1,300 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, engineers relied on permafrost to keep the temperature of the seeds stable in the event of a power failure. But they didn’t take climate change into account. Ministry officials say the seeds have never been threatened and will remain safe, but they have taken preventive measures against leaks and possible thermal instability.

A prehistoric threat and unstable soil

The age of permafrost means that it contains a wide variety of bacteria and viruses among its organic matter, microorganisms that have been preserved thanks to low temperatures, lack of oxygen and darkness. Biologists from the University of Aix-Marseille in France have discovered fragments of RNA (ribonucleic acid) from the 1918 Spanish flu virus in corpses buried in mass graves in the Alaskan tundra, and claim that the microorganisms that cause smallpox and bubonic plague are probably also buried there.

It’s not science fiction. In 2016, an anthrax outbreak in Siberia affected eight people and killed a 12-year-old boy. Biologists determined that the outbreak was caused by the consumption of reindeer meat from an area where animals infected with the bacteria were buried under the permafrost in 1941. The heat wave brought the Bacillus Anthracis bacteria to the surface, a microorganism that can live for hundreds of years and was dormant in the frozen soil.

On the other hand, about 35 million people live on the permafrost, mostly in Russia, where large cities like Yakutsk, Batagai, Norilsk and Vorkuta are built on special concrete piles sunk 30 meters into the permafrost. In these cities, as well as on some roads, some infrastructures have begun to show signs of instability due to the melting of the subsoil. In some areas of the Siberian tundra and taiga, methane fumes have appeared and are curving the ground outwards like “bubbles” under the grass.

The threat of no return

© Harshil Gudka on Unsplash

Scientists warn that the thawing of permafrost is considered one of the most radical irreversible factors for climate, since in the event of the release of gases, a vicious circle can be initiated that feeds back on itself and accelerates degradation. This is a good example of how the alteration of any environmental factor, even if it occurs in the far-off Arctic or in the rivers of the Amazon, affects the climate of the whole planet.

From April to October 2021, the IPCC will present to experts and governments the reports that will make up the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) to be published definitively in 2022, in time for the first global assessment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). At that time, governments will review the progress made towards achieving their goal of keeping global warming well below 2°C while, at the same time, continuing efforts to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C. Hopefully, it will not be too late for permafrost.