The easterly wind storm caused by storm Gloria hits the breakwater of the port of Barcelona. © AlfonsPuertas _ https://www.instagram.com/alfons_pc/ _ Image from Observatori Fabra in Barcelona

Floods, hurricane winds, giant waves… Violent weather phenomena have been the protagonists in recent months in many areas of the world and, especially in Europe, they have surprised us with their special violence, unusual extent and seasonal rarity. According to the Spanish State Agency for Meteorology (AEMET in Spanish), from 2019 onwards the frequency and intensity of extraordinary adverse phenomena has shot up in the western Mediterranean, where three storms in just nine months have been classified as “historic”.

The Mediterranean, a sea in turmoil

From the 18th to the 22nd April 2019, in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula, it rained twice as much as the average for an entire spring in just five days. In September of the same year a cold drop originated, which caused the highest rainfall in the last 50 years in the region of Murcia, with seven deaths and the environmental disaster of the Mar Menor, one of the most serious in Europe. In this same episode, the Vega Baja region of Alicante recorded the highest accumulated rainfall in the region’s average since records are available (1879). In many towns in the area there were absolute records of rainfall in 24 hours with much difference from the data observed in the last 50 years.

The third episode was last January’s storm Gloria that surprised meteorologists because of its unusual genesis. It was a squall of Atlantic origin that moved towards the Mediterranean and was not created by a process of explosive cyclogenesis; neither was it particularly deep from the barometric point of view, as the atmospheric pressure did not drop much: it was in the range of 1010 – 1006 millibars (mb), when the normal pressure for powerful Atlantic squalls is of 970 – 990 mb.

The virulence of the storm Gloria was determined by the presence of an anomalous anticyclone over Great Britain that reached an atmospheric pressure in its center higher than 1050 mb, the highest value registered by the British meteorological service since 1957. The shape, elongated in an east-west direction, and the extension of this anticyclone, created with Gloria an enormous pressure gradient causing extremely strong east winds (east wind storm) that reached land loaded with subtropical humidity. The anticyclone was in charge of injecting cold continental air that, once it collided with the humid air, caused a very severe winter storm, with enormous waves, intense and persistent rains, strong winds, abundant snowfall in mountain areas, extreme minimum temperatures and lightning in practically the entire east side of the Iberian Peninsula.

Historical records of rain for the month of January were recorded on the 21st: 27 mm (liters per square meter) more than the previous record of almost 75 years ago accumulated at Barcelona airport; in Tortosa, double the previous record of almost 90 years ago was collected; and in Daroca, in Aragon, there was almost twice as much rain as the maximum rainfall almost 70 years ago. That day was also the day with the highest number of electrical discharges in January in the region of Valencia since the discharge network began operating in the 1990s: 3,035 lightning strikes in one day.

Damages caused on the coastline of Blanes, many of whose beaches disappeared. © Elena Barredo

An exceptional sea storm

But it was the sea storm that impressed us the most with its intensity and the magnitude of the damage caused, with shocking images shared through social networks and the media. A historic wave of 14.2 meters was measured on the east coast of Mallorca and, according to the records of the Valencia measurement buoy, it is estimated that the height of the waves exceeded 13 meters in this area, also record values.

According to the Spanish Ministry for Ecological Transformation and Demographic Challenge, it is estimated that the storm, which caused 13 deaths, gave rise to 54 million euros in damages to beaches and infrastructure along the more than 2,000 kilometers of coastline from Murcia to Girona, including the Balearic Islands.

The Ebro Delta flooded after storm Gloria. © Gabriel Villena.

The sea tore away millions of tons of sand, some beaches receded by as much as 35 meters, others simply disappeared; and waves of more than eight meters swept away many promenades, broke walls, reached houses and premises, and flooded streets. The violent runoffs filled rivers, streams and torrents with all kinds of debris and vegetation that, once dumped into the sea, were returned to the shore by the waves and the wind. Some of the waste that covered the beaches consisted of branded food containers that had not been available for decades, a symptom of the large amount of dispersed pollution in the watersheds or forgotten dumps that the runoff unearthed.

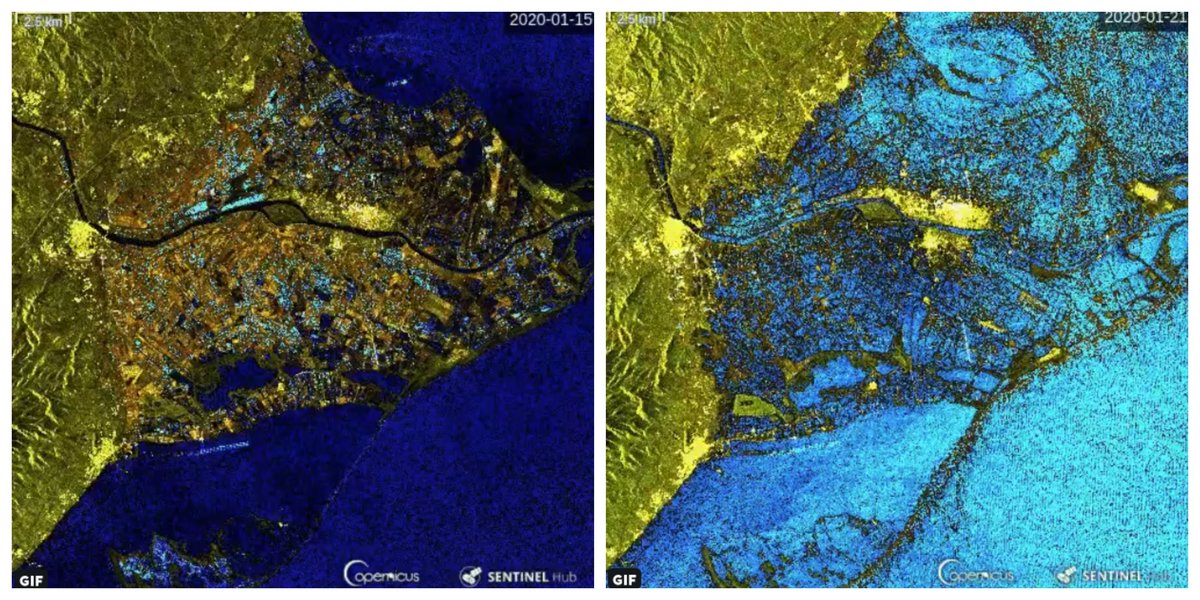

The Ebro Delta showed one of the most desolate images as it was almost entirely flooded by sea water. The storm practically wiped out 3,000 hectares of rice fields, destroyed mussel beds and fish farms, erased beaches from the map and dealt a severe blow to the biodiversity of the wetland, a unique spot in Europe with more than 340 species of birds that have their habitat there.

Image of the Ebro Delta on the 15th January 2020, left, and on the 21st, flooded by the sea after storm Gloria. Copernicus Sentinel.

A coastal model in crisis. An adapted coast?

If the Mar Menor disaster last September has led to a review of agricultural and water management schemes and the general governance of the territory in the face of the floods caused by the cold drops, the storm Gloria adds the maritime factor to the risks of extreme phenomena.

The equation Risk = Dangerous phenomenon + Exposure + Vulnerability provides new values in the Spanish Mediterranean coast and the conclusions are very useful to establish the most effective actions in the face of a type of phenomenon that science predicts will increase in the short and medium term. A warmer sea, whose level tends to rise, coincides with the scenario envisaged by the IPCC in its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), so the dangerous phenomenon factor is likely to increase. This consequently increases the exposure of people and goods, as the area of incidence of the phenomena expands and, following the same logic, so does their vulnerability when they receive an impact for which there was no foresight or preparation.

To combat the virulence of the phenomena, efforts to mitigate climate change must continue to be redoubled. But in order to reduce exposure and vulnerability, adaptation models must be considered now.

In the case of the Mediterranean coast the challenge is of considerable magnitude and complexity. The disaster in the Ebro Delta was partly announced by scientists and farmers as an interruption in the supply of sediment had been detected after 70 dams were built in the river basin between 1950 and 1970 for irrigation, urban water supply, electricity generation and flood control. Before 1950, water carried between 20 and 30 million tons of sediment into the delta every year; its lack also aggravated the problem of natural subsidence, aggravated by the rising sea levels of recent years and salinization.

The experts of the European Life Ebro-Admiclim program assure that it would be necessary to contribute between one and two million tons of additional sediments to recover the natural state of the wetland; sediments that, according to this pilot program, could be achieved by causing controlled floods with enough force to drag solid materials and open the lower gates of the dams.

Solutions based on nature

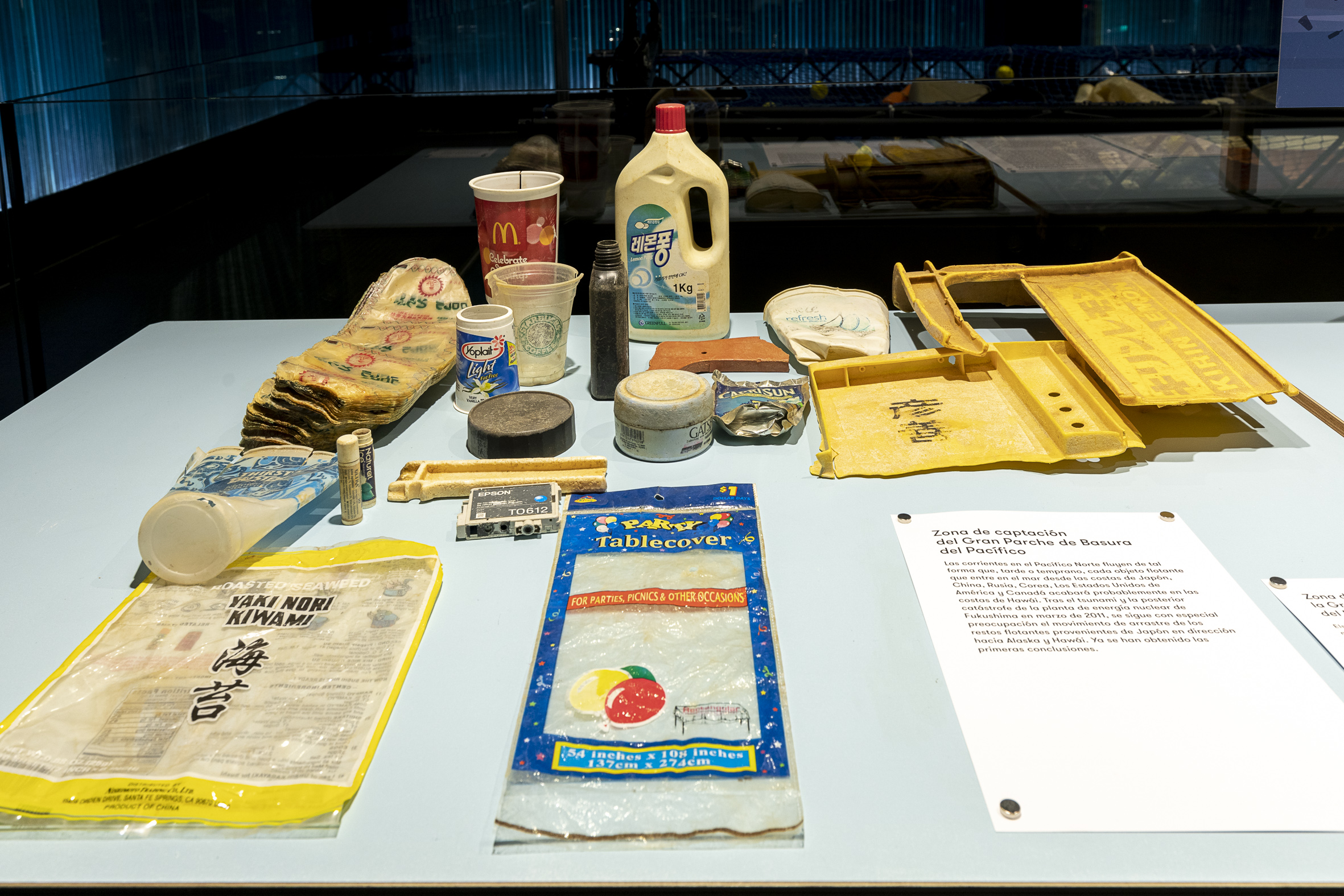

The violent storms turn the riverbeds into pollution vectors towards the soil and the sea. Image of the exhibition “Plastic Seas. From the problem to the solution” at the Roca Barcelona Gallery.

In the case of the urbanized line of the coast the problem involves the tourist and urban development models, and waste management. Many municipalities are faced with the dilemma of how to rebuild what has been damaged. In Spain, the disaster adds elements to the controversial Coastal Law enacted in 1988 but it is clear that solutions should preferably be based on natural ones, although there is no general solution and each case should be studied in particular.

In many cases, the contribution of sand, a common practice in the “construction” of beaches, is no longer useful or sustainable. Placing submerged rock barriers to stop the waves, raising sand dunes as retaining dikes on the beaches and using soft and natural materials in the design of promenades separated from the sea are essential measures. But the problem of exposing developed areas and infrastructure that were hitherto thought to be far from the threat of the waves represents a more uncertain solution.

On the other hand, the pollution of the sea by the flood of solid and chemical waste is another of the serious environmental aspects of this type of episodes. The fresh water of the rivers thus becomes a vector of pollution that seriously damages the marine fauna and the coastal territory, causing incalculable damage to the natural capital. The exhibition Plastic Seas. From the problem to the solution, which can be visited at the Roca Barcelona Gallery until April, shows the magnitude of the environmental aggression caused by the waste the sea receives and which contributes to increasing the exposure and vulnerability of any area of the world.