There is a cold war over Nile water. The tension over managing a water flow that averages 2,830 cubic meters per second has strained relations for decades between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, which occupy most of its enormous hydrographic basin of approximately 3.254 million square kilometers, home to some 450 million people.

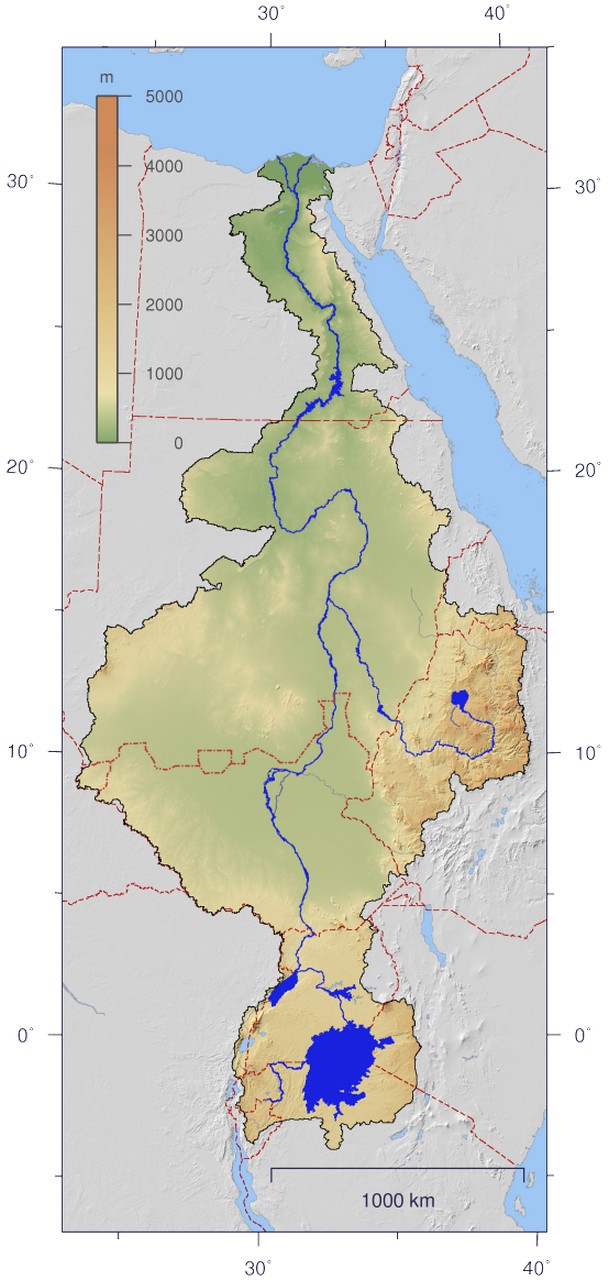

The large Nile basin is the stage for the biggest political disagreement over access to water resources in recent times. © Ismael Alonso

A river of life in the desert altered in the Anthropocene

The cyclical floods of the Nile, which the ancient Egyptian culture linked to the god Happi, have been a mystery since the time of Herodotus (484-425 BC). It was revealed when British naturalists in the mid-19th century observed that they were due to rainy periods in the Ethiopian mountains and the jungles of Uganda and South Sudan. The silt that settled on the riverbanks was a natural fertilizer that allowed agriculture in an otherwise desert-like land.

The first intervention that altered this cycle was the construction of the Aswan Dam, which began in 1959 under President Gamal Abdel Nasser and was completed in 1970. Located some 850 kilometers south of Cairo, one of the reasons for its construction was the generation of electric power and the provision of water to boost irrigation beyond the banks of the river.

The construction of the Aswan Dam led to the forced displacement of some 100,000 to 120,000 people due to the creation of the large reservoir (Lake Nasser), not to mention the damage to the riparian economy.

However, its construction led to the forced displacement of some 100,000 to 120,000 people due to the creation of the large reservoir (Lake Nasser), not to mention the damage to the riparian economy and the cost of altering downstream ecosystems.

But most significantly, the cycle of sedimentation, which had a life span of hundreds of thousands of years, disappeared. Agriculture had to adapt to irrigation planning; canals and pumping facilities were built to irrigate crops, and many farmers had to resort to chemical fertilizers to supplement those provided by the silt.

The uniform flow also brought salinity problems in some areas, such as the Nile Delta and other areas where floodwaters carried away accumulated mineral salts.

A post-colonial dispute

Water management problems followed the independence of Egypt and Sudan. In the late 1950s, the two countries engaged in disputes over the Nile. In the first agreement, they shared the flow: 55.5 billion cubic meters for Egypt and 18.5 billion cubic meters for Sudan. The figures were based on the historical use of the river’s water according to the British colonial past and did not include Ethiopia.

According to this approach, Egypt had the greatest need to ensure flow control: in its mainly desert climate, Nile water accounts for up to 98% of its water resources. No other country has such an overwhelming proportion, which weighed decisively at the negotiating table.

For Sudan, the focus was on security to provide irrigation and sufficient water for its developing network of hydroelectric dams. The signing of the so-called Agreement for the full utilization of the Nile waters in 1959 was a diplomatic success that, although precarious, offered a glimpse of a future of understanding.

The Grand Ethiopian Dam steps in, and a cold war breaks out

In 2011, the situation took a radical turn when Ethiopia announced the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a mega-project to hold 70 billion cubic meters of water in a 247-square-kilometer reservoir. The essence of the project was to generate some 6,000 megawatts of electricity, which the Ethiopian government considered essential to kick-start its project to industrialize the country and sell energy to neighboring countries.

The GERD project upset the more or less stable political balance between Egypt and Sudan. A genuine “water cold war” was declared, with rumors of possible armed attacks on the dam instigated by Mohamed Morsi, then president of Egypt, which were never confirmed. To ease the tension, in 2015, the two countries met with Ethiopia and signed a framework agreement to cooperate on using Nile water. However, the document did not address all concerns, and the disputes remained unresolved.

The Nile River basin is divided into the Blue Nile Basin, which flows through Ethiopia, and the White Nile Basin, which flows mainly through South Sudan and has its sources in the territories of Burundi and Rwanda.

Egypt was concerned about maintaining the water flow in the Aswan Dam, and Sudan was anxious about controlling the floods it had been suffering systematically since climate change altered the intensity of seasonal rains. Ethiopia argued that the GERD would regulate the floods, but this was not the case in 2020 nor in 2021, when floods, this time caused mainly by the flow of the White Nile that had devastated South Sudan, again ravaged its banks.

The map of the Nile River Basin helps to understand the situation. Upstream, the river branches in a complex way. The Blue Nile, coming from Ethiopia, and the White Nile, which flows through South Sudan, converge in Sudan. The GERD dam is located only 45 km from the Sudanese border, so flow disturbances have an immediate impact on the country.

The bar is high for SDG 17

In 2022, Ethiopia started the final filling of the GERD, in a unilateral decision that provoked protests from Egypt and Sudan and turned the political tension up a notch. However, despite difficulties, efforts continue. Last August, delegations from the three countries met in Cairo to negotiate a “legal agreement” on the management of the basin. Nevertheless, the Ethiopian government continues to refuse the demands of its neighboring countries.

In recent years, data have become available that complicate the decision. Several scientific reports have corroborated the increase in salinity of the Nile Delta, caused both by alterations in the flow —already started with the Aswan Dam— and by the overexploitation of groundwater and the rise in sea level. The productivity of farmers in the delta, a crucial alluvial zone for the Egyptian economy, is being eroded year after year.

The management of the Nile Basin is the most significant international cooperation challenge on water resources today. © Islam Hassan /Unplash

Moreover, the Nile River Basin extends through the areas of most outstanding climatic contrast in the world: from the Tanzanian rainforests to the Egyptian desert, its waters run through the broadest range of flora and fauna. As the river flows into the Mediterranean, it is one of the great environmental and climatic regulators of southern Europe and North Africa.

The management of the Nile Basin is the most significant international cooperation challenge on water resources today. The solution must come and prove that the targets of SDG 17 can be met: “Successful delivery of a development agenda requires inclusive partnerships (at global, regional, national and local levels) on principles and values, as well as on a shared vision and goals that put people and the planet first.” More than ever, we need to make this a reality. Water must unite, not divide.